Amelia Earhart: Aviatrix, Feminist Fashionista, Villager

This is one in a series of posts marking the 50th anniversary of the designation of the Greenwich Village Historic District. Click here to check out our year-long activities and celebrations.

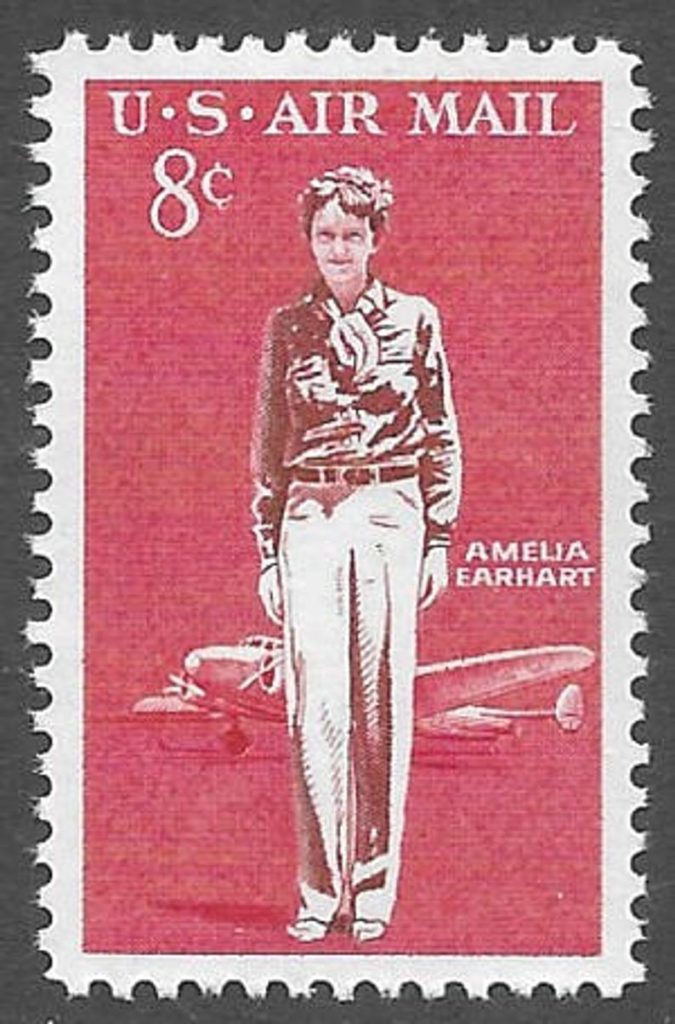

Aviatrix Amelia Earhart is a household name for shattering a record-breaking 18,415-foot glass ceiling in her airplane. Almost as famous is her mysterious disappearance during her attempted around-the-world flight in 1937. Earhart was less a household name for her other qualities and achievements, which we celebrate today: a staunch and vocal feminist, an author, a social service worker, a fashion icon, and, for a time, a Greenwich Village resident.

Before She Became “The Queen of the Air”

Amelia Mary Earhart was born on July 24, 1897, in Atchison, Kansas. She went to high school in Chicago and enrolled in a junior college, but during a visit to her sister in Canada, she developed an interest in caring for soldiers wounded in World War I, especially with the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918. She left junior college to become a nurse’s aide in Toronto, and in 1919 moved to New York to study medicine at Columbia. She only stayed there for one year, deciding to move to California, where her parents had relocated in 1920. It was there, in Long Beach, California, that she went on her first airplane ride. She recounted understanding, during her first trip into the sky, that this was where she was meant to be.

Earhart asked Anita “Neta” Snook, a pioneer aviatrix herself, for lessons, saying simply: “I want to fly. Will you teach me?” And so, Earhart’s first lesson was on January 3, 1921. In 1921 she bought her first plane, and two years later she earned her pilot’s license, following in the footsteps of the women aviators before her, like her teacher, and like Bessie Coleman, known as “Queen Bess,” the first Black woman to earn an international pilot’s license — two years before Earhart (Coleman opened her own flight school so other Black women would not face the same obstacles she did).

In the mid-1920s Earhart moved to Boston, where she became a social worker at the Denison House, a settlement home for immigrants. While she was doing that work, she also got work as a sales representative for Kinner Aircraft in the Boston area and wrote local newspaper columns promoting flying. As her local celebrity grew, she laid out the plans for what would become The Ninety-Nines, an organization for female pilots.

Earhart in Greenwich Village

In 1927, Earhart relocated to Greenwich Village. She was flying more and more, and it was impeding her ability to hold her stable job at the Denison House in Boston. Her writing had been picked up by Cosmopolitan, and the famous magazine offered her a job. In addition to her other work, she was also a real fashionista and was already becoming a fashion icon, especially since she would wear slacks to fly, which was quite unusual at the time. Earhart accepted the “Aviation Editor” position at Cosmopolitan, but wanted to keep doing her social work as well. So, she wrote to Greenwich House, a settlement house which is still doing incredible community work in the West Village. Greenwich House offered her a room and a staff position – for when she was in town, at least – and she accepted, living at their still-extant main building at 27 Barrow Street in the Greenwich Village Historic District from 1927-1929.

Charles LeBoutillier, who had known Earhart in Boston, is quoted as seeing Earhart in the Village:

Peering under the open hood of a car parked near Greenwich House on Barrow Street. “It was a beautiful car—looked like a Stutz Bearcat—and she took care of it herself… I’d seen her at the Boston airport after her Atlantic flight with her arms full of flowers. She was living in an apartment in the Village that fall, in that settlement house. I think most of the people in the neighborhood knew who she was but nobody took much notice. She ate in a cafe with a courtyard—one a lot of us went to—and someone said she liked to talk about Edna St. Vincent Millay’s poetry. She didn’t seem different from us—just an ordinary person.”

In 1931, she married the wealthy George Palmer Putnam. Putnam was Vice President of the Explorers Club and a member of many other prestigious clubs who had divorced his wife for Earhart, been working for some years as Earhart’s publicist, and campaigning to make Earhart one of America’s most famous women. In the wonderfully-written New York Times marriage announcement, we learn:

Since living in New York Miss Earhart has resided first at the Greenwich Settlement House and, until now, at the American Women’s Association Clubhouse here [located at 356 West 58th Street]. Mr. Putnam has a country home at Rye, N.Y., but the couple for the present will occupy an apartment at the Hotel Wyndham, 42 West Fifty-eighth Street.

Earhart’s Feminism

In addition to her piloting feats, Earhart was known for encouraging women to reject constrictive social norms and to pursue various opportunities, especially in the field of aviation. In 1929 she helped found an organization of female pilots that later became known as the Ninety-Nines. Earhart served as its first president.

Her interest in fashion continued, and she developed a clothing line for women who “live actively.” She made a flying suit with loose trousers, a zipper top and big pockets. Vogue advertised it with a two-page photo spread. The clothing line expanded from there, and in 1933 it was released in department stores like Macy’s.

Earhart was also a member of the National Woman’s Party and an early supporter of the Equal Rights Amendment.

Earhart kept her maiden name when she was married G.P. Putnam, and specifically wrote to The New York Times reminding them to never call her Mrs. Putnam. Before the wedding, Earhart sent Putnam a letter addressing her concerns about marriage. Hesitant about marriage in the first place, Putnam proposed six times before Earhart agreed. Even then, she demanded an equal partnership, with her career being treated as a valid part of their life. She would not be held to a “medieval code of faithfulness.”

That life-changing time in the Village

During the time she lived in the Village, Earhart became the first woman to fly across the Atlantic on June 17, 1928. In 20 hours and 40 minutes, she flew herself to international fame, earning invitations to air shows, flights, and organizations across the country. She wrote about the flight in 20 Hrs. 40 Min. (1928) and undertook a lecture tour across the United States.

She published her book during this time and took it on tour across the country. She bought another airplane, a single-engine Lockheed Vega. In 1929, Earhart won third place – and $875 – in a Women’s Air Derby, affectionately coined the “Powder Puff Derby,” Earhart called it “a chance to play the game as men play it, by rules established for participants as flyers, not as women.”

Of her amazing fortune and skill in flying, Earhart said: “My ambition is to have this wonderful gift produce practical results for the future of commercial flying and for the women who may want to fly tomorrow’s planes.”

Final Flight And Disappearance

In 1937 Earhart set out to fly around the world in a twin-engine Lockheed Electra, with Fred Noonan as her navigator. On June 1 the duo began their 29,000-mile journey, departing from Miami and heading east. Over the following weeks, they made various refueling stops before reaching Lae, New Guinea, on June 29. At that point, Earhart and Noonan had traveled some 22,000 miles. Reportedly on the morning of July 2, 1937, Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, took off from Lae on what was supposed to be one of the last legs in their historic attempt to circumnavigate the globe. Their next destination was Howland Island in the central Pacific Ocean, some 2,500 miles away. A U.S. Coast Guard cutter, the Itasca, waited there to guide the world-famous aviator in for a landing on the tiny, uninhabited coral atoll. But Earhart never arrived on Howland Island. Battling overcast skies, faulty radio transmissions and a rapidly diminishing fuel supply in her twin-engine Lockheed Electra plane, she and Noonan lost contact with the Itasca somewhere over the Pacific. Despite a search-and-rescue mission of unprecedented scale, including ships and planes from the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard scouring some 250,000 square miles of ocean, they were never found.

There have been endless theories about whether Earhart had been a spy and was shot down, whether she and Noonan had ended up on one of the islands in the area, near Japan, or elsewhere. Some thought that she came back to the United States and assumed a new name.

Needless to say, no conclusive evidence has been found about what happened to the pair and their plane, and the mystery continues to this day. Speculation about her fate and the mystery behind it can be found in a song by Joni Mitchell, an episode of Star Trek: Voyager, in which Earhart is abducted by aliens, a biopic in which Earhart was played by Hillary Swank, and so many more.

Earhart: Lost in the West Village?

Some have even speculated that Earhart’s true fate was that she actually got and remained lost forever in the winding and eccentric streets of the West Village. As per this spoof piece that ran in Vanity Fair 75 years after Earhart’s last flight:

__VF Daily:__Girl, where are you!

Amelia Earhart: I have no idea!

What do you mean?

So, I’m somewhere in the West Village. The street sign says W. 10th Street and W. 4th Street, but how can that be?

Oh boy.

And 11th Street and 9th Street are not immediately before and after 10th Street? And 5th Street and 3rd Street are nowhere near anywhere. I just don’t understand why the grid doesn’t work down here. And then I was at the intersection of Waverly Place and Waverly Place. Waverly Place and Waverly Place, can you explain that to me?

Navigating the West Village’s idosyncratic tangle of streets may be almost as challenging as circumnavigating the globe. But if the unconventional and trailblazing Earhart was lost in Greenwich Village, we’re confident she’d find herself right at home.

Earhart is one of the dozens of trailblazing women on our Transformative Women tour on our Greenwich Village Historic District 50th Anniversary Map — see them all at www.gvshp.org/gvhd50tour.

After Amelia disappeared,not only the Navy but 3 monthes later a British expedition also,arriving on Gardner island for checking colonisation possibilities and knowing her disappearance, 3 days the island was searched no any sign of them nor plane,read the report.

Nevertheless a group of researchers,even the famous

Ballard were searching on and around Nikumaroro island as its called know.

However 200 facs point to the deadth of Amelia and Fred Noonan on Saipan,beginning 1945 their remains

collected by US G.I ‘s and now somewhere in a box in an archive? what a sad and not deserved ending.

Why? Cause the coverup is going on and on by US government for what reason? Shame on them

Check sites like “Earhart Truth” Jan de Jong morotai@gmail.com

Nicely done.