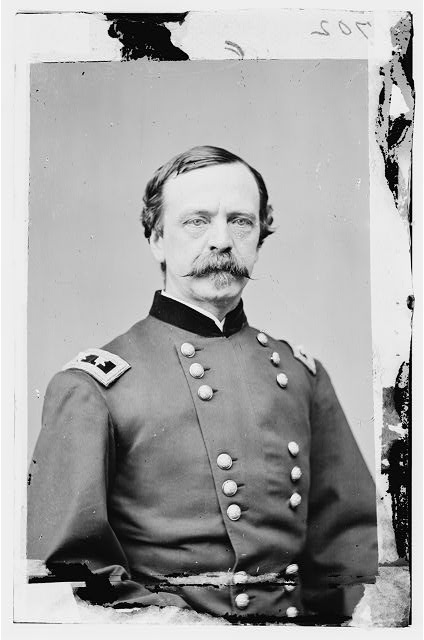

Gettysburg General Daniel E. Sickles’ Complicated Legacy

Politician, Civil War Major General, diplomat, Greenwich Village resident, and downright “rascal” Daniel E. Sickles (October 20, 1819 – May 3, 1914) has one of the most contentious, strange, and multifaceted biographies in American history. Colorful and controversial, Sickles is remembered as much for his role in shaping the outcome and memory of the Battle of Gettysburg, as for his scandalous murder of Philip Barton Key II and his groundbreaking legal acquittal. Between these two defining events, however, Sickles was deeply involved in local and national politics, maintaining relationships with many of the most powerful and renowned figures of his era. From 1881 to 1883, Sickles was also a resident of 14-16 Fifth Avenue, a building in the Greenwich Village Historic District now under threat of demolition.

During the Civil War, Union Army Major General Sickles recruited the New York regiments that became the Excelsior Brigade in the Army of the Potomac, and served as the commander of the Third Army Corps. On the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg, which lasted from July 1 to July 3, 1863, Sickles defied the orders of Major General George Meade and decided to lead an unauthorized advance on Peach Orchard. The decision is considered controversial, to say the least, as detractors argued it put the Union Army at risk of defeat, though of course this ended up as a decisive Union victory which served as the turning point in the Civil War. Nonetheless Sickles, who lost his leg in the battle, was awarded a Medal of Honor. His questionable move, and the events that followed, transformed the famous battle, and remained a subject of debate for generations.

Following the war, Sickles undertook strenuous efforts to defend his decisions and shape the historical record of the Battle of Gettysburg. He donated his amputated limb to the Army Medical Museum in Washington DC, now the National Museum of Health and Medicine, and returned often to the museum and to Gettysburg to speak about his experience. Sickles also played a major role placing monuments on the field and establishing the Gettysburg National Military Park. When the New York State Legislature founded the New York Monuments Commission for the Battle of Gettysburg, Sickles was appointed chairman.

A Tammany Hall Democrat, Sickles was already a figure of considerable controversy and attention even before the Civil War and the Battle of Gettysburg. He was often in the news for his legal and romantic woes, which culminated in his sensational murder of Philip Barton Key II in 1859. Key, the district attorney of the District of Columbia and the son of Francis Scott Key (who wrote The Star-Spangled Banner), had been having an affair with Sickles’ wife, Teresa Bagioli Sickles. Sickles made history when he was acquitted based on his defense of temporary insanity, the first use of this defense in the United States.

Outside his two most prominent points of fame and notoriety, Sickles maintained a lengthy career in New York politics throughout his life, beginning with his position as member of the New York State Assembly in 1847. He was appointed the Secretary of the Legation at London by President Franklin Piece, serving from 1853 until 1855, and later became a member of the New York State Senate from 1856 to 1857. Sickles was then elected a Democrat to the Thirty-Fifth and Thirty-Sixth Congresses (March 4, 1857 until March 3, 1861), and a chairman of the New York State Civil Service Commission from 1888 until 1889. In 1890, he became a sheriff in New York City, and three years later he was elected again as a Democrat to the Fifty-Third Congress (March 4, 1893 until March 3, 1895). For five years, Sickles also lived in Madrid as the U.S. Minister to Spain.

For all his time in the local and national limelight, Sickles was less well known for his close personal relationships with an astonishing number of political figures, including United States presidents Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, James Buchanan, and even a young Theodore Roosevelt. He was also acquainted with author Mark Twain, who wrote extensively about Sickles in his memoirs and who would live across the street from Sickles’ Greenwich Village home in later years (Twain was also associated with literary trailblazer Bret Harte, another, earlier resident of 14-16 Fifth Avenue).

Unquestionably, Major General Daniel E. Sickles had a profound impact upon the Civil War and 19th century political and legal history. Following Sickles’ death on May 3, 1914, a military funeral procession marched up Fifth Avenue from near his former Greenwich Village home at 9th Street to St. Patrick’s Cathedral in his honor.

Village Preservation has received a series of extraordinary letters from individuals across the world, expressing support for our campaign to protect 14-16 Fifth Avenue. For more information on Daniel Sickles, please read the letter of support from David Eicher, the chief editor of Astronomy magazine and the author of 9 books on American history, including The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War.

To help protect 14-16 Fifth Avenue from demolition, click here. To read more about our campaign and the building’s history, click here.