Samuel F.B. Morse: A Brilliant Artist and Inventor With A Complicated, Troubling Legacy

Samuel Finley Breese Morse was an artist, inventor, and would-be-politician. While there was much to admire about his legacy and accomplishments, there was also much to condemn and deplore. Reading his biography, one might think (or even wish) that there were actually several different Morses. One was an inventor who helped bring telegraph technology and the earliest forms of electronic communication into broad usage in the U.S. and eventually abroad. Another was a romantic portraitist who studied abroad and arrived in Greenwich Village to become the first professor of painting in America at New York University, where he lived and painted at 100 Washington Square East. Yet another, more troubling Morse, shared and promoted many of the all-too-common nativist and racist sentiments of his time, seeking to become Mayor of New York on anti-immigrant and anti-Roman Catholic platforms in 1836, and arguing in his writings in the 1850s and 60s for the moral basis for slavery. But these were all the same Morse, and while he was much less successful in the latter endeavors than he was in the former ones (he earned only 1,496 votes in his Mayoral run), they are all part of the complicated, sometimes-inspiring and sometimes-repugnant legacy of our one-time neighbor.

Samuel Morse was born on April 27, 1791 in Charlestown, Massachusetts to Elizabeth Ann Breese, and Jedidiah Morse, a distinguished geographer and Congregational clergyman. Samuel attended Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, and then Yale College (now Yale University). His scholarship has been described as “indifferent” to all but the then-mysterious subject of electricity and the painting of miniature portraits. Morse went abroad to England to study portraiture, and on his return in 1825 he settled in New York City and joined the artist community of Greenwich Village, painting portraits that combined technical competence and a bold rendering of his subjects’ character with a touch of the Romanticism he had imbibed in England.

Although often poor during those early years, Morse was sociable and at home with the intellectuals, the wealthy, the religiously orthodox, and the politically conservative. The circles in which he moved introduced him to prominent figures such as the French hero of the American Revolution, the Marquis de Lafayette, whose attempts to promote liberal reform in Europe Morse (somewhat paradoxically and inexplicably) ardently endorsed, as well as the novelist James Fenimore Cooper.

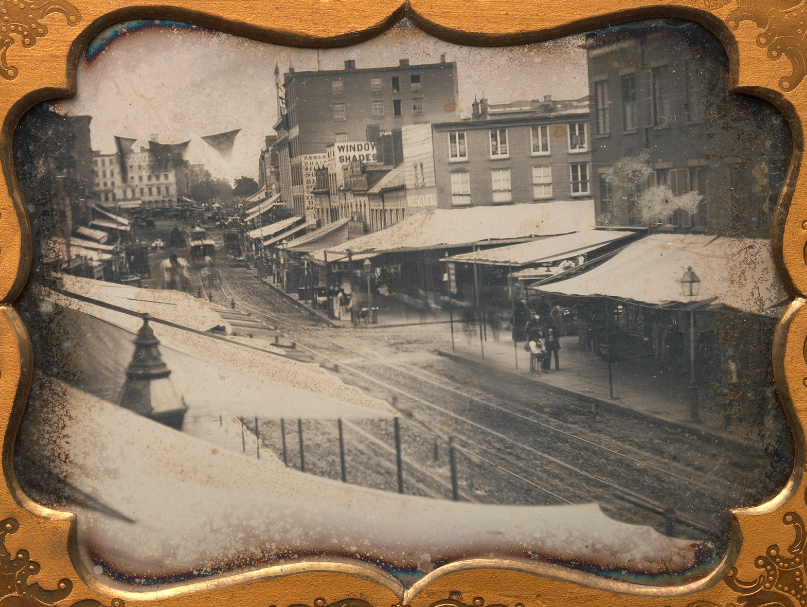

In 1832, Morse became the first professor of painting and sculpture in America at what was then the fledgling NYU campus. Three years later he acquired studio space for himself and his students in the newly-built neo-Gothic University Building (demolished in 1894 to make way for the present Silver Center, home of the Grey Art Gallery). He was involved with all kinds of arts at NYU, including some of the earliest daguerreotypes (an early form of photography) ever taken.

During that time, Morse also founded and named himself the first president of the National Academy of Design, which sponsored an art school and organized frequent public exhibitions of work by its members. The National Academy’s headquarters were first located at 663 Broadway near Bleecker, then moved at the corner of Fourth Avenue and Tenth Street, and then in the 1850s and 1860s was located at 58 East 13th Street. The National Academy was soon joined by other arts organizations, the Century Association at 46 East Eighth Street (formerly 24 Clinton Place), and the Tenth Street Studio Building at 15 (later 51) 10th Street near Sixth Avenue. These organizations created a seat of arts and creativity in the Village that was world-renowned and world-changing.

Morse continued, even as his life in the arts was taking off, with his study of electricity. In 1838 he and his friend Alfred Vail developed the Morse Code. He would refine it to employ a short signal (the dot) and a long one (the dash) in combinations to spell out messages. He didn’t invent the telegraph, but his key improvements allowed the medium to be deployed on a broader level, transforming communications worldwide. Although the idea of an electric telegraph had been put forward in 1753 and electric telegraphs had been used to send messages over short distances as early as 1774, Morse believed that his was the first such proposal. He probably made his first working model by 1835; he made his first public demonstration on January 6, 1838, and publicly demonstrated it again at NYU on January 24, 1838.

After lean, difficult years of lobbying, financial struggle, and technical improvements, Morse secured funding from Congress to build wires across the United States, and received a patent for his invention in 1844. On May 11th of that year, his telegraphed message from Baltimore to Washington was the first of its kind.

Following the routes of the quickly-spreading railroads, telegraph wires were strung across the nation and eventually, across the Atlantic Ocean, providing a nearly-instant means of communication between disparate towns, cities, states and nations for the first time. Newspapers joined forces as the Associated Press, to pool payments for telegraphed news from foreign locales. Railroads used the telegraph to coordinate train schedules and safety signaling. President Abraham Lincoln received battle reports at the White House via telegraph during the Civil War. And ordinary people used it to send important messages to loved ones as they traveled.

In 1847 Morse bought a country house which he called Locust Grove, an estate overlooking the Hudson River near Poughkeepsie. He had an Italian villa-style mansion built there, and spent his summers there with his large family of children and grandchildren, returning each winter to New York City.

Morse died on April 2, 1872, in New York City, having made advances in both the arts and in practical technology that truly transformed the world. Morse’s 1837 telegraph instrument is preserved by the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., while his estate, Locust Grove, is now designated a national historic landmark.

Morse’s accomplishments in the field of electronic communication are well known (even those who have never seen or heard Morse Code are aware of its importance). His prominence in the arts is perhaps less well-known, as we tend to view the sciences and the arts as separate and perhaps even mutually exclusive realms, though his legacy there was great too. His abhorrently bigoted and pro-slavery views have been largely forgotten or overlooked over time, and had less of a lasting impact than his other accomplishments. But they nevertheless deserve to be remembered as part of what defined this paradoxical figure who once lived in our midst.

Fascinating!!!

I rode by the monument in Central Park today (it’s off Fifth Ave at 72nd St.) and for a moment couldn’t think who “MORSE” might be.

Thank you!

FYI: The person depicted in that image is not Samuel Morse. It is a daguerreotype of an unknown young man TAKEN by Samuel Morse (“Portrait of a Young Man.” 1840) Morse was the first commercial photographer in the United States, having met with Louis Daguerre in Paris in 1839, just before the daguerreotype process was announced to the world.