Ferlinghetti and Rosset: Censorship-Battling Superheroes

Our neighborhoods are not only places where great literature was written. It’s also where great literature was published, sometimes at great legal peril, and where tectonic-shifting battles against censorship were led and won. Nowhere is that more true than in the area South of Union Square, where art, commerce, and activism collided. And perhaps no two figures were more critical in those efforts, especially in the mid-20th century, than author and publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and publisher Barney Rosset.

Lawrence Ferlinghetti passed from this world in March of 2021 at the ripe age of 101. One of the most influential figures in 20th-century literature, he outlived the century he helped define.

Born in Bronxville, N.Y. in 1919, Ferlinghetti’s story is almost Dickensian in its narrative. The future poet laureate of San Francisco lost his father before he was born, and his mother to mental illness not long thereafter. He was taken in by his uncle and aunt, members of the same Monsanto family after whom the chemical company is named. He spent years with his aunt as a boy in Strasbourg, France, but upon return to the U.S. was placed in an orphanage in Chappaqua, N.Y. as his aunt was deemed unable to care for him. He was then fostered by a wealthy couple, Anna and Pressley Bisland. He attended Bronxville schools and became a championship basketball player, until getting into mischief, at which point the Bislands sent him to Northfield Mount Hermon School, a prep school in Massachusetts. He continued his studies at the University of North Carolina, Columbia University, and later at the Sorbonne. His well-heeled upbringing and education seem rather unexpected for an iconoclast whose writings channeled anarchist leanings and sociopolitical revolution.

Ferlinghetti moved to San Francisco in 1951 and founded City Lights Book Store in the North Beach neighborhood. He established a publishing house of the same name that specializes in world literature, the arts, and progressive politics.

In 1955, Ferlinghetti began publishing the Pocket Poets Series of books, out of the City Lights bookstore, in San Francisco. His own verse appeared in Number One, titled “Pictures of the Gone World,” but it was Beat poet Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl and Other Poems” (1956) that landed Ferlinghetti, wearing his publisher’s hat, in jail resulting in a First Amendment trial in 1957. Ferlinghetti had been prescient in sensing that Ginsberg’s poem would upset Eisenhower-era mores. The American Civil Liberties Union had assured Ferlinghetti that they would defend him should any objections to the drug use and sexual acts depicted in “Howl” arise. With the ACLU’s help, he won the case.

Which brings us to the East Coast iconoclast from our neighborhood.

Perhaps no person or entity was more responsible for dismantling censorship and restrictions on literature with controversial sexual or political themes in the 20th century than Grove Press and its publisher Barney Rosset. Called “the era’s most explosive and influential publishing house,” an astonishing five extant buildings South of Union Square were home to the Grove Press, while a sixth, 61 Fourth Avenue, served as Rosset’s residence until his death in 2012. Though founded in 1947 on Grove Street in the West Village, the foundering Grove Press would not rise to prominence until purchased by Barney Rosset in 1951, who would move the publishing house to a variety of locations throughout this area. Under Rosset, Grove introduced American readers to European avant-garde literature and theater, which had often previously been restricted from publication or distribution in the United States, including French writers such as Jean Genet and Eugene Ionesco. In 1954, Grove published Samuel Beckett’s play “Waiting for Godot” after more mainstream publishers had refused to do so. Grove also published the works of Harold Pinter and was the first American house to publish the unabridged complete works of the Marquis de Sade.

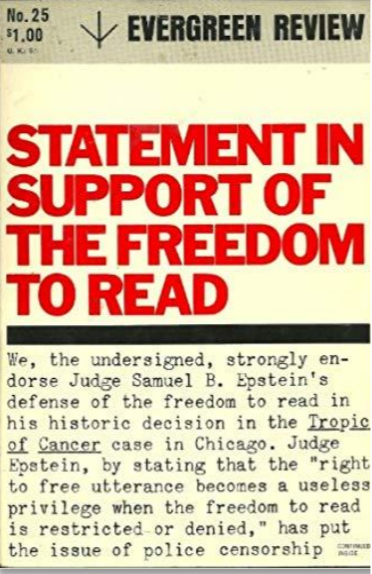

Grove was also known for publishing most of the American Beat writers of the 1950s, including Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and William S. Burroughs, as well as poets like Frank O’Hara and Robert Duncan. Rosset and Grove also published the Evergreen Review between 1957 and 1973, a literary magazine whose contributors included Bertolt Brecht, Albert Camus, Edward Albee, LeRoi Jones, and Timothy Leary. It also published controversial and overtly political works by the likes of Che Guevara and Malcolm X.

Among their censorship battles, Grove Press published an uncut version of D.H. Lawrence’s “Lady Chatterley’s Lover” in 1959. After the U.S. Post Office confiscated copies of the book sent through the mail, Rosset sued the New York City Postmaster and won at both the state and federal level. Building upon this success, in 1961 Grove published Henry Miller’s “Tropic of Cancer,” which since its release in 1934 could not be published in the United States due to the inclusion of sexually explicit passages. Lawsuits were brought against dozens of individual booksellers across many states for selling it, but the U. S. Supreme Court’s Miller v. California decision in 1973 ultimately cleared the way for the book’s publication and distribution. Grove also published William S. Burrough’s “Naked Lunch,” which was banned in several parts of the country, including Boston, due to its explicit descriptions of drug use. That ban was reversed in a landmark 1966 opinion by the Massachusetts Supreme Court.

Rosset both lived and worked out of a loft at 61 Fourth Avenue for decades until his passing in 2012. In a 2009 interview from his loft just before his death, Rosset said “all of Grove Press’s life was within about four blocks of here.” If that didn’t give 61 Fourth Avenue sufficient credibility as a top tier cultural landmark, the 1889 loft building was also the home of the studio of artist Robert Indiana (“LOVE”) in the 1950s, and in the late 1950s and early 1960s of the Reuben Gallery, which created the “Happening.”

In 1962 after a three-year censorship battle, Rosset and Grove released the American edition of William S. Burroughs’ “Naked Lunch,” while continuing to push boundaries by publishing gay-themed fiction like John Rechy’s “City of Night” and the previously-banned writings of the Marquis de Sade.

Also in 1962, thesde two titans of literary freedom, Rosset and Ferlinghetti, finally came together in their efforts to dismantle censroship. Rosset and Grove Press railed support from leading literary luminaries like Lawrence Ferlinghetti in support of their various censorship battles, publishing the famous July/August 1962 issue of the Evergreen Review Statement in Support of the Freedom to Read, which included the lower level court decision striking down the ban on Tropic of Cancer along with a statement supporting the decision and calling for an end to the legal appeals and similar bans signed by 198 leading American writers and critics and the heads of sixty-four publishing companies.

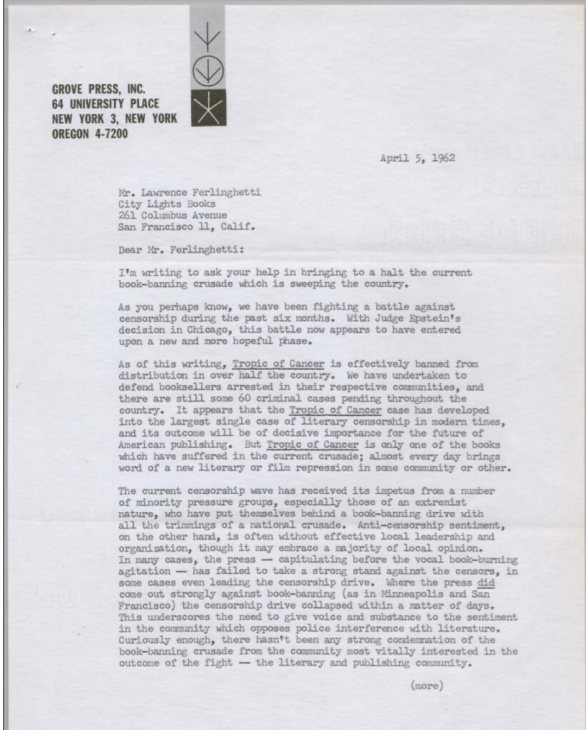

On April 5th, 1962, Rosset wrote to Lawrence Ferlinghetti appealing to him to join his colleagues in the censorship fight. Ferlinghetti joined the battle, which took many years to win, bringing together two of the foremost and most successful advocates of a free literary press in this country for a long partnership on one of the most important anti-censorship legal battles in the country’s history.

The remarkable concentration of sites connected to Barney Rosset and Grove Press speaks to the profound significance of the area South of Union Square in connection to the history of our city and country. It’s no coincidence that Barney Rosset, Grove Press, and the Evergreen Review and Theatre were located in this area; it was a place of tremendous cultural ferment and innovation in the mid-to-late 20th century, perhaps more so than any other part of New York at the time, as the city was emerging as the cultural capital of the world. Painters, writers, publishers, and radical social organizations all gravitated towards this area in part because of the synergy of progressive social and cultural movements oriented towards affecting change. Their efforts were aided by an historic building stock that lent itself to adaptive reuse and which maintained a distinct sense of place that went against the grain of homogenization of the American landscape in the mid-to-late 20th century.

Fortunately, all of these buildings survive, some in perfectly intact condition, others modestly changed but still bearing clear connections to their period of significance. Village Preservation is working diligently to make certain that these historic places are preserved for generations to come. You can help us in our efforts by writing to key city officials urging them to support our proposal for landmark designation of the area. And by donating!