Remembering the former Pennsylvania Station

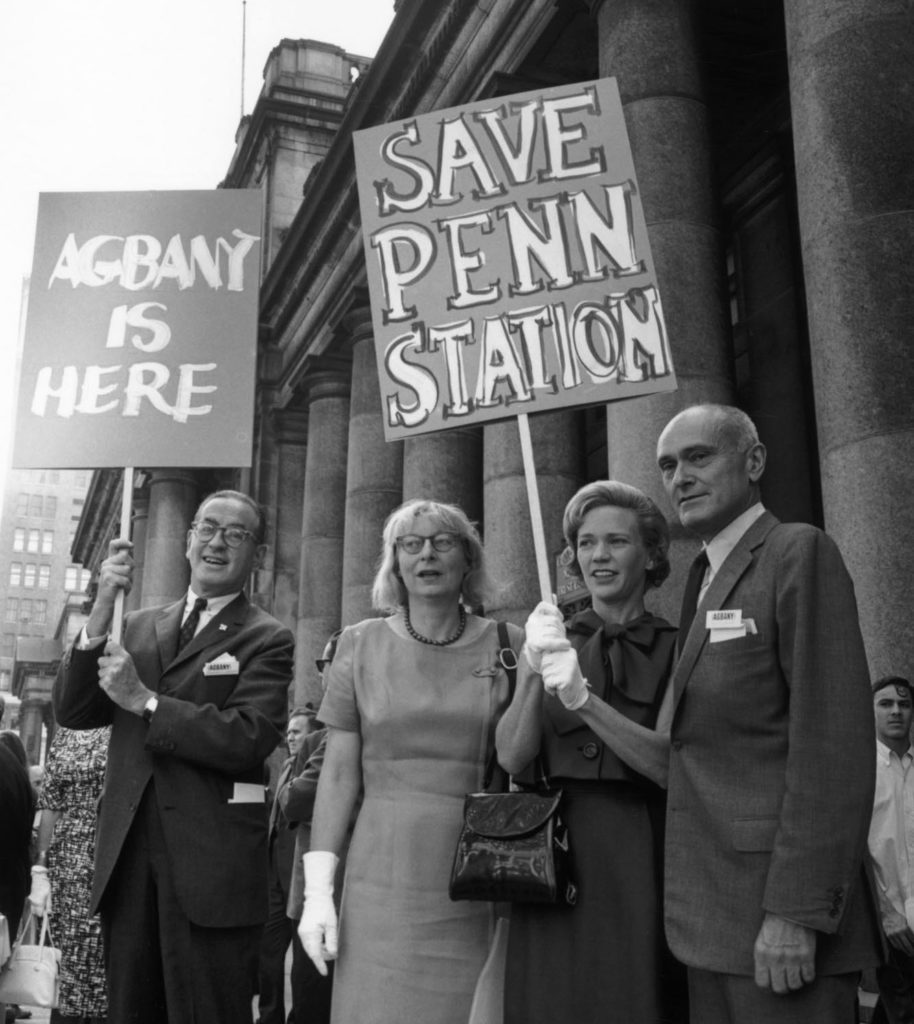

On August 2, 1962, a group of concerned citizens protested in front of Pennsylvania Station, the McKim, Mead, and White Beaux Art structure in pink granite that spanned two full city blocks. The impending demolition of this historic structure was opposed by leading architects, artists, and critics, including Philip Johnson, Aline Saarinen, and Villagers Eleanor Roosevelt, Jane Jacobs, and Norman Mailer. The destruction of the building is often referred to (somewhat misleadingly) as the beginning of New York City’s preservation movement. While the demolition of Penn Station does not necessarily mark the beginning of the preservation movement, it galvanized a generation of thinkers and actors to recognize the value of our built environment and our history, helped lead to the establishment of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, and catalyzed a strong preservation movement in our city.

The demolition of Penn Station is considered by many a seminal moment in 20th century New York’s history; following closely on the heels of the publication of Jane Jacob’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities, it was a watershed in raising public consciousness about and turning public opinion against the growing destruction of our city’s built fabric for questionable urban renewal projects and short-term corporate profit. The Pennsylvania Railroad, which owned the station, was experiencing a decline in rail travel and the company wanted to use their biggest asset, the land and air rights that comprised Pennsylvania Station, to generate funds. In exchange for the air-rights to Penn Station, the Pennsylvania Railroad would get a new, smaller station located completely below street level at no cost, and a partial stake in the new Madison Square Garden Complex which would be built in the place of the station by developer Irving M Felt. When this plan finally came to light, several architects formed the Action Group for Better Architecture in New York (AGBANY), organizing a protest and a letter writing campaign. Demolition of the station took three years, and images of the destruction further fueled the public’s outrage at the loss. Comparing the grandeur of the original Penn Station, which was flooded with natural sunlight, with its flourescent-lighted subterranean replacement, architetural historian Vincent Scully noted “One entered the city like a god; one scuttles in now like a rat,” and many New Yorkers agreed. The New York Preservation Archive Project has more resources for the history of the building and its demolition on its website.

Articles in the New York Times, the real estate blog Curbed, and the New York City based blog Gothamist all paid tribute to the 50th anniversary of these protests. What does this tell us? New Yorkers are still concerned with preserving our collective landmarks. Even with the passage of the Landmarks Law in 1965, landmarks and landmark districts do not come easily, as those familiar with the work of GVSHP know. Groups like the “Responsible Landmarks Coalition” will lead you to believe that the regulation that comes with the designation of individual landmarks and landmark districts cripples new development and construction job growth in New York City. But architects, preservationists, and contractors know better.

As demolition began of Penn Station, New York Times architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable notably wrote “Any city gets what it admires, will pay for, and, ultimately deserves. Even when we had Penn Station, we couldn’t afford to keep it clean. We want and deserve tin-can architecture in a tin-horn culture. And we will probably be judged not by the monuments we build but by those we have destroyed.”

Let’s hope this warning, and the memory of the former Pennsylvania Station, is not forgotten.

To see images of Penn Station being demolished in our Historic Image Archive, click here.

Great piece, thanks for pointing readers to the New York Preservation Archive Project’s entry on Penn Station. Glad that we can all continue to learn from this loss and turn something destructive into something productive.