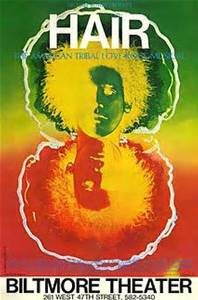

Groundbreaking Musical Hair Premieres at the Public Theater October 17, 1967

The year was 1966. Lyndon Baines Johnson was in his second term as president, America was in the trenches in Vietnam. Both President Kennedy and Malcom X had been assassinated, and the nation had watched on television years of violence surrounding desegregation and the horrors of the Vietnam War.

The year was 1966. Lyndon Baines Johnson was in his second term as president, America was in the trenches in Vietnam. Both President Kennedy and Malcom X had been assassinated, and the nation had watched on television years of violence surrounding desegregation and the horrors of the Vietnam War.

Visionary and legendary producer Joseph Papp was disgusted with the current discourse in the theater. “I am looking for plays that have some passionate statement to make that is commensurate with the times we are living in,” he would later say. “I don’t like plays that give me pat answers. There aren’t any. I don’t like story plays. I don’t like sentimental plays. But I like plays that are hard to explain, that leave you with more questions than answers, plays that have abstractions that I don’t totally understand.”

With that appetite for radical, visceral theater, he went looking for a way to transition from his revolutionary program of Free Shakespeare in the Park to a body of work in his new space downtown that would be an agent for change. An admirer of the Living Theater, established downtown in the late 1940’s by Judith Malina and Julian Beck, he was looking for theater that h ad real blood and guts. The kind of theater, as he put it, that was a “form of education, where you should be engaged spiritually and emotionally, and feel you know more when you leave than you did when you came in. You get your money’s worth not by looking at the scenery but inside your soul.” He was looking to create a theater that was not complacent, that was “doubting, questioning…”

ad real blood and guts. The kind of theater, as he put it, that was a “form of education, where you should be engaged spiritually and emotionally, and feel you know more when you leave than you did when you came in. You get your money’s worth not by looking at the scenery but inside your soul.” He was looking to create a theater that was not complacent, that was “doubting, questioning…”

Papp was at the time commuting back and forth to New Haven where he was teaching a class. It was at the Yale Repertory Theatre where he saw the Open Theater’s production of Megan Terry’s “Viet Rock” and first met Gerome Ragni, an Open Theater actor, who handed him the script of what would become the musical “Hair.” Originally Papp consigned the script to the bottom of his “to be read” pile. But on one of his many trips from Yale back to New York, Ragni spotted him on the train and sat next to him. He pressed his cause and handed the producer a few pages of lyrics to read. The thing that initially struck Papp was the feeling of loneliness of young people that the lyrics evoked. He wanted to do theater that was of the times they were living in and a sad little scene about a young man talking about going off to war struck a nerve. Papp invited Ragni and his collaborator James Rado to come to the Public to discuss the work. After they had plunked out a few of the tunes on the piano for Papp and Gerald Freedman, associate artistic director at the time, Freedman told them to find a composer. They felt that the tunes were terrible.

They returned with Galt MacDermot. As MacDermot put it, “I was an ex-organist and choir director from Montreal who had received my music degree in South Africa and had spent most of my life playing jazz and rock-and–roll on the piano. Having grown up in Canada, I wasn’t familiar with many Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals. I had had a hit song called “African Waltz” in England and here. To be honest, there was a lot of African and West Indian influence in what I was writing, but people didn’t know too much about that kind of music then. It was all rock-and-roll to them.” Papp and Freedman loved the music. Papp felt that the project was extremely provocative. In July of 1967, he informed his associates that he was going to produce the first rock musical. He assigned Gerald Freedman, an accomplished musician himself, to direct the piece.

The ensuing rehearsal period was by all accounts an unmitigated disaster. Freedman collided with Ragni and Rado on every word and decision. He complained that they often came to rehearsals stoned and undisciplined. The entire production team came to view the two as hippies who lacked the professional skills to write a play. Anna Sokolow, the choreographer, quickly began not speaking to Freedman. The conflict became so heated between the two of them that Freedman finally tendered his resignation. Papp did not refuse it. Instead he appointed Sokolow as the director, who promptly installed Rado in one of the roles he had written and had wanted to play from the start. A few days before the first preview, the Scenic Artists and Brotherhood of Painters, Local 829, went on strike, which trapped the scenery in a warehouse behind a picket line.

As scenic designer Ming Cho Lee described the mess: “The final dress rehearsal was hopeless. Nineteen thirties modern dance with half-finished scenery set to rock-and-roll.” After seeing it, Papp promptly fired Sokolow and wired Freedman, then in Washington D.C., to come home to finish directing the play. Freedman came back, fired Rado and returned the production back to his original staging.

Called “the first hippie musical,” the show opened to mixed reviews. It had music unknown to the musical theater vernacular. Songs such as “Aquarius,” “Good Morning Starshine” and “Frank Mills” would become enormous hits recorded by dozens of singers and groups. The musical itself would go on to be a pacifist symbol throughout the world. The innovations of non-linear structure and a new approach to music were ground breaking innovations that “Hair” brought to American musical theater genre.

We saw HAIR at the Cheetah in 1967 and it was amazing.