LGBT History in All Corners: the South Village

June is Pride Month, an especially exciting time to be in the Village. LGBT history is closely tied with our neighborhoods, and this month we’re highlighting the LGBT history of the West Village, East Village, South Village, and NoHo. All of these sites can also be found on our GVSHP Civil Rights and Social Justice Map, and we encourage you to check it out and let us know about any other histories or locations you think should be added. Today we’re focusing on the South Village; read about the West Village LGBT historic sites here, and those in the East Village here.

June is Pride Month, an especially exciting time to be in the Village. LGBT history is closely tied with our neighborhoods, and this month we’re highlighting the LGBT history of the West Village, East Village, South Village, and NoHo. All of these sites can also be found on our GVSHP Civil Rights and Social Justice Map, and we encourage you to check it out and let us know about any other histories or locations you think should be added. Today we’re focusing on the South Village; read about the West Village LGBT historic sites here, and those in the East Village here.

The South Village and nearby areas are home to some of the oldest pieces of LGBT history in the city (the neighborhood is also near and dear to GVSHP’s heart, as we waged a 15 year campaign to secure landmark designation for the entire area). In addition to gay life, the neighborhood was also home to the headquarters of many important LGBT rights activists and organizations. Below are a few of the standout sites that reflect the social and political landscape of LGBT life and activism in this neighborhood.

Black Rabbit (183 Bleecker Street)

In the 1890s, the Black Rabbit, located at 183 Bleecker Street in the building still standing on this site, offered live sex shows as part of its draw. It was closed by the police in 1899, reopened, and was raided again in 1900 by the Society for the Suppression of Vice. The Black Rabbit and the Slide (at 157 MacDougal Street) together represent the earliest known sites of LGBTQ activity in New York in the nineteenth century.

Portofino Restaurant (206 Thompson Street)

LGBT history was made in the South Village more than fifty years ago, at 206 Thompson Street, where the Italian restaurant Portofino was located from 1859 until 1975. It was a discreet meeting place frequented on Friday evenings by lesbians. The 2013 groundbreaking Supreme Court decision that overturned the federal Defense of Marriage Act had its roots here in the 1963 meeting of Edith S. Windsor and Thea Clara Spyer. Edith “Edie” Windsor was born in Philadelphia in 1929 to a Russian Jewish immigrant family. She graduated from Temple University and later moved to New York City to pursue a master’s degree in mathematics at New York University. She eventually became one of the first female senior systems programmers at IBM. Thea Clara Spyer was born in Amsterdam in 1931 to a Jewish family that fled to the U.S. to escape the Holocaust before the Nazi invasion of the Netherlands. She was expelled from Sarah Lawrence College after a guard caught her kissing another woman, but later received her bachelor’s degree from the New School for Social Research, and a master’s degree and PhD in clinical psychology from the City University of New York and Adelphi University, respectively. Windsor and Spyer began dating after meeting at Portofino in 1963.

Spyer proposed in 1967 with a diamond brooch, fearing Windsor would be stigmatized at work if her colleagues knew about her relationship. The couple married in Canada in 2007 after that country legalized same-sex marriage, and when Spyer died in 2009, she left her entire estate to Windsor. Windsor sued to have her marriage recognized in the U.S. after receiving a large tax bill from the inheritance, seeking to claim the federal estate tax exemption for surviving spouses. The Defense of Marriage Act was enacted on September 21, 1996 and defined marriage for federal purposes as the union of one man and one woman, and allowed states to refuse to recognize same-sex marriages granted under the laws of other states. United States v. Windsor was a landmark civil rights ruling which came down on June 26, 2013 in which the Supreme Court held that restricting U.S. federal interpretation of “marriage” and “spouse” to apply only to opposite-sex unions is unconstitutional. It helped lead to the legalization of gay marriage in the U.S. Two years later on June 26, 2015, the Supreme Court ruled in Obergefell v. Hodges that state-level bans on same-sex marriage were unconstitutional.

Daughters of Bilitis (final location, 141 Prince Street)

Originally founded in San Francisco in 1955, the Daughters of Bilitis was the first lesbian organization in the United States. By 1957, New Yorkers were beginning to comment on the absence of a chapter in New York City. Lorraine Hansberry anonymously wrote a blurb in The Ladder (the organization’s newsletter, which had become the first nationally distributed lesbian publication in 1956) calling for a presence on the East Coast. The following year, Barbara Gittings and Marion Glass founded the New York chapter.

The initially tiny chapter shared an office with the gay male organization Mattachine and bounced around the city for the next 13 years. The chapter’s final location was in a loft at 141 Prince Street, in a building that is still standing, one block outside of Greenwich Village. By 1972, editing The Ladder ran out of funds and folded, however the 14 year run of Daughters of Bilitis inspired the creation of dozens more lesbian and feminist organizations across the country.

Gay Activist Alliance Firehouse (former location, 99 Wooster Street)

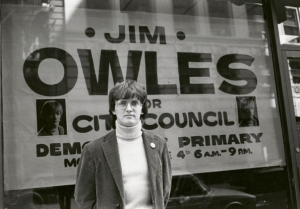

The building at 99 Wooster Street was formerly home to the Gay Activists Alliance, one of the most highly influential LGBT groups of the post-Stonewall era. Founded in 1969 by Marty Robinson, Jim Owles, and Arthur Evans, the group was an offshoot of the Gay Liberation Front.

Their location in an abandoned city firehouse at 99 Wooster Street became the first gay and lesbian organizational and social center in New York City. Their “zaps” and face-to-face confrontations were highly influential to other activist and political groups. In 1974 they were targeted by an arson fire and subsequently were forced to cut back on functions. They officially disbanded in 1981.

186 Spring Street Residence

In the era immediately following the Stonewall riots, 186 Spring Street was home to a number of important figures of the Gay Rights movement, serving for a time as a “gay commune” of sorts. Bruce Voeller, who lived in the building, co-led the first delegation of gay rights leaders to ever meet with the White House, helped end the federal government’s ban on employing gay people, helped get homosexuality removed from the American Psychiatric Association’s list of mental illnesses, got the very first piece of federal gay rights legislation introduced, and won the first Supreme Court case establishing rights for gay parents.

Another resident, Jim Owles, was the first openly gay person to run for public office in New York. Owles, along with Voeller and Arnie Kantrowitz, founded several of the country’s first and largest LGBT organizations. The 1824 house was purchased by a developer who originally claimed he would preserve the house, but later announced plans to demolish it to make way for a condo development. GVSHP fought to preserve the building but the Landmarks Preservation Commission failed to act. In 2012, the developer went ahead with plans to demolish the historic home.

GVSHP Civil Rights & Social Justice Map

GVSHP has released a map of sites of significance in the history of civil rights and social justice movements in Greenwich Village, the East Village, and NoHo. In addition to LGBT history, the map also covers African-American, Women’s, Hispanic, and immigrant history, as well as many other locations important to civil rights and social justice movements – view it at www.gvshp.org/civilrightsmap. The map is updated regularly and if you know any sites that should be included, feel free to email it, along with any information (and sources!) to info@gvshp.org.

One response to “LGBT History in All Corners: the South Village”