Is there a Doctor in the Village? Yes, and Her Name Was Elizabeth Blackwell

Continuing our celebration of Women’s History, today we look at a seminal figure not only in women’s history but medical history as well — Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell. You may already know that she was the first woman in the United States to receive her medical degree. But did you know that she not only lived and practiced in our area, but also started the first women’s hospital staffed exclusively by women, as well as the first women’s medical school, both located in our neighborhoods? In fact, three sites are identified on GVSHP’s Civil Rights and Social Justice Map that are associated with Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell and her groundbreaking work.

Born on February 3, 1821, in Bristol England, Blackwell was born into a liberal family which stressed education. She and her family moved to the United States in 1832, first settling in New York City and then moving to Cincinnati, Ohio. Following the terminal illness and death of a friend who felt she would have been better served by a female doctor, Elizabeth decided to pursue her medical degree. Every school she applied to turned her down until 1847 when Geneva Medical College in Western New York State accepted her. The story goes that the faculty, assuming that the all-male student body would never agree to a woman joining their ranks, allowed them to vote on her admission. As a joke, they voted “yes,” and she gained admittance, despite the reluctance of most students and faculty.

Blackwell received her degree on January 23rd, 1849, becoming the first woman in America to receive a medical degree and thus to formally practice medicine. Following her graduation in 1849, she worked in clinics in Paris and London, and in 1851 she returned to the United States. She moved to New York City and rented a floor in the building still located at 80 University Place, which was at the time numbered 44 University Place, and used it as her medical office and home. Despite insults and objections from her landlady and neighbors, Blackwell began providing medical services to patients at this location, most of whom were females and members of the local Quaker community.

In response to the squalid conditions and a lack of available medical care on the Lower East Side, Blackwell opened a dispensary in a since-demolished house at 207 East 7th Street which consisted of a single rented room. Here Blackwell would see and treat destitute women and children three days a week. She moved the dispensary to 36 Avenue A/136 East 3rd Street (present-day 150 East 3rd Street) for more space, and in 1854 the New York Dispensary for Poor Women and Children was incorporated and the institution moved to a small house on the corner of East 15th Street and Second Avenue.

But in 1857, Blackwell made an even greater leap forward when she established the first hospital for women, staffed by women, and run by women called The New York Infirmary for Women and Children. It was located in the house at 58 Bleecker Street, which was originally numbered 64 Bleecker Street. Built in 1822-1823, the house was erected for James Roosevelt, great-grandfather of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who lived there until his passing only ten years before Blackwell began renting there. Blackwell’s hospital opened its doors on May 12, 1857, the 37th birthday of Florence Nightingale, whom Blackwell had befriended earlier in her career. The hospital was open seven days a week and provided medical care for needy women and children free of charge. The staff at first consisted of Elizabeth, director; her sister Dr. Emily Blackwell, surgeon; and Dr. Marie Zakrewska. The hospital provided practical medical instruction for women studying for their medical degree, which was unavailable elsewhere. The hospital was operated solely by a staff of women, and its opening was attended and praised by the noted abolitionist preacher Rev. Henry Ward Beecher.

However, many others were not enthusiastic about this enterprise, and according to Blackwell she was told that no one would rent her a space for this purpose, that the police would shut the hospital down, that they would not be able to control the patients, and that no one would financially support such an institution. However, the hospital was able to operate and over time views on women in medicine evolved. The hospital was responsible for innovations in hygiene critical in preventing disease and in educating the public on those benefits, such as bathing ailing patients and encouraging them to keep clean. Blackwell also launched a “Sanitary Visitor” program to visit the needy in their homes in the slums and improve hygiene. The program later expanded into the hospital’s “Out Practice Department,” a precursor of the Visiting Nurse Service. The first Sanitary Visitor, Rebecca Cole, was also the first black woman doctor.

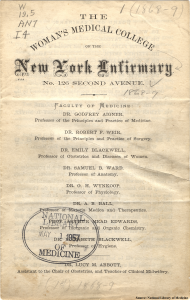

According to one source, the hospital moved in 1861 to 126 Second Avenue (present-day 128 Second Avenue) where Blackwell would also establish the first women’s medical college. In 1865 the trustees first applied for a charter to become a medical college, and in 1868, The Woman’s Medical College of the New York Infirmary began, with fifteen students and a faculty of nine, including Elizabeth as Professor of Hygiene, and Emily as Professor of Obstetrics and Diseases of Women. The college was only staffed by women, and offered four-year educational programs during a time in which medical schools, catering almost exclusively to men, only offered two-year programs. In its thirty-one years of successful operation, the Women’s Medical College educated more than 350 female physicians.

Elizabeth left for England shortly after the opening of the college, and the work of the college and hospital was carried on by her sister Emily. Elizabeth spent the rest of her years in England continuing on her work. She died there in 1910.

For more information on Blackwell and other revolutionary women in our area, see the GVSHP Civil Rights and Social Justice map or our page on the historic plaque we placed on Blackwell’s former clinic on Bleecker Street.