Villager David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake At Night at the Whitney Museum

GVSHP took a trip to the Whitney Museum’s exhibition called “David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night,” and learned about this incredible Villager, artist, poet, and activist. His work from the 1990s, before his death of complications from AIDS, agitated for change and strove for visibility, supporting and nurturing a community of artists through hard times. Though firmly rooted in the New York of the 1990s, Wojnarowicz’s art still feels relevant today. The exhibition reflected a person who was figuring out how to live with his angers and pleasures, how to make activist art, and how to find his place in the world.

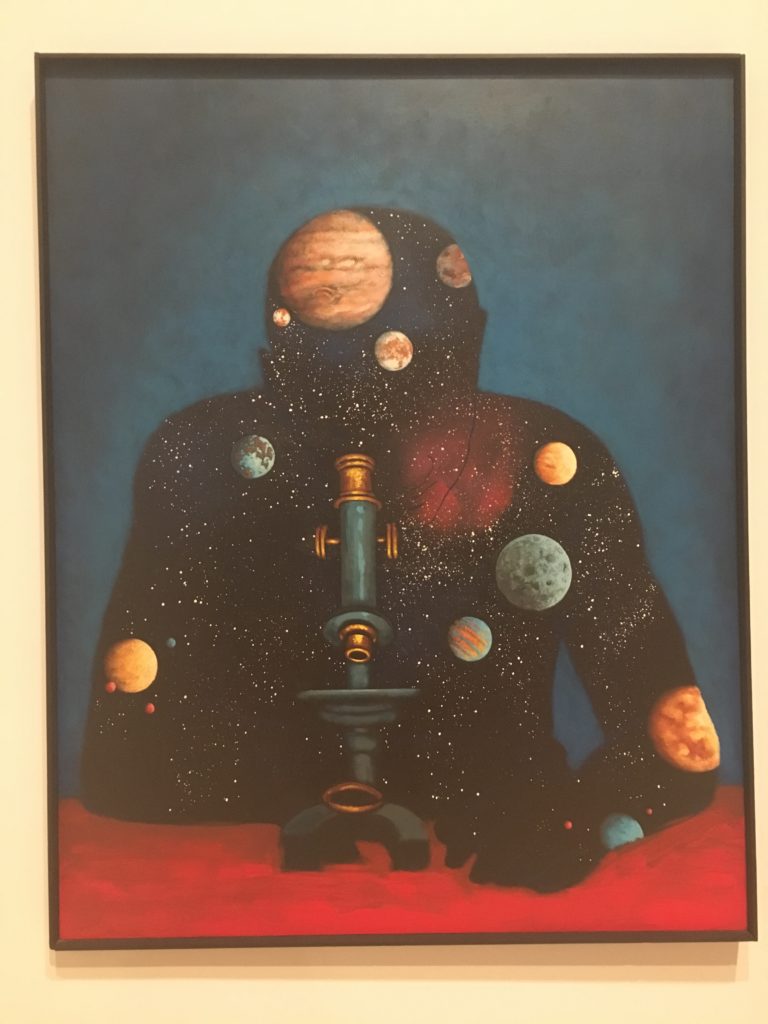

David Wojnarowicz: Self Portrait

Early Life

David Wojnarowicz (pronounced voy-nah-ROH-vitch) was born in Red Bank, New Jersey in 1954. His parents divorced and disappeared when he was 2 years old, leaving him in a succession of temporary homes. He was placed in the foster system at 8, where he experienced enough cruelty that he ran away from that home at 9. He spent his teen years as a street hustler. He dropped out of high school at 15, with no formal art training and a deep love for writing poetry.

When Wojnarowicz was 20 he met the East Village photographer Peter Hujar on the Christopher Street piers. After a short sexual relationship, they decided to be friends, but became much more. This marked a turning point for Wojnarowicz, and Hujar became a mentor, an intimate caretaker, and chosen family member. Hujar was 20 years older, and was already living and working in the Village’s art scene. Hujar and Wojnarowicz would make art together, taking trips around the New York City area to take photographs and video and to graffiti art on the abandoned structures of the Greenwich Village piers.

Art and Public Life

Wojnarowicz’s artwork caught the public eye in the 1980s, a time when New Wave and No Eave music, photography, performance, and neo-expressionist painting made New York, in the words of the Whitney, “a laboratory for innovation.”

The first art exhibition that featured Wojnarowicz’s work was curated by New York artist Nan Goldin in 1989, and it was called “Witness Against our Vanishing.” The funding for the exhibition came from the National Endowment for the Arts, and the funding got pulled because of the “controversial” nature of the work – the collection was meant to raise awareness about the AIDS crisis, which was being essentially ignored and rejected by the U.S. government. “An inconceivable number of friends, lovers, and strangers were dying due to government inaction,” according to the Whitney. Wojnarowicz jumped on the opportunity and sued the National Endowment for the Arts, raising a lot of media attention and awareness about him, his art, and the AIDS fight. At that time, Peter Hujar and Wojnarowicz himself had been diagnosed. This changed the nature of Wojnarowicz’s work and introduced a clear interest in death, which can be seen in many of his artworks.

The Whitney’s exhibition description gives Wojnarowicz and his work some important cultural context:

Wojnarowicz’s work documents and illuminates a desperate period of American history: that of the AIDS crisis and culture wars of the late 1980s and early 1990s. But his rightful place is also among the raging and haunting iconoclastic voices, from Walt Whitman to William S. Burroughs, who explore American myths, their perpetuation, their repercussions, and their violence. Like theirs, his work deals directly with the timeless subjects of sex, spirituality, love, and loss. Wojnarowicz, who was thirty-seven when he died from AIDS-related complications, wrote: “To make the private into something public is an action that has terrific ramifications.”

Continuing the Work and the Fight

After the lawsuit against the National Endowment for the Arts, Wojnarowicz also sued the American Family Association of Tupelo, Mississippi, an anti-pornography political action group that Wojnarowicz accused of misrepresenting his art and damaging his reputation. He won the lawsuit and gained more notoriety for himself and his cause. At this time, Wojnarowicz was making art that was pointedly political, fusing image and text, and creating art from collages of maps, dollar bills, the words of government officials, sheet music, and more. He would paint over those collages, building new art out of the found objects. Wojnarowicz’s art is bold in its colors and subjects, engaged deeply with pop culture, and very occupied by the body. The art is sexy – both in its text and visual content – as Wojnarowicz was committed to presenting his whole self, as a gay man who felt that his body and desires were silenced by the world around him. These small details of his art are balanced by very clear, big ideas about history and art as tools of agitation, learning, and empathy.

When Peter Hujar died in 1987, Wojnarowicz spent two hours photographing his body as a final act of devotion and documentation. These photos were used in his art in multiple ways, and are on display at the Whitney. Wojnarowicz moved into Hujar’s loft on East 9th Street and lived there until his death.

Death and Legacy

Wojnarowicz died of AIDS-related illness in New York City in 1992. He was 37 years old. His partner, Tom Rauffenbart, traveled to Washington DC in 1996 with members of the AIDS activist organization ACT UP to take part in one of their “Ashes Actions,” during which Wojnarowicz’s ashes were spread on the lawn of the White House in continuing protest of President George H.W. Bush’s inaction on funding and supporting AIDS research. Wojnarowicz is remembered as a visionary multimedia artist, poet, musician, and activist.

“David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake At Night” is on view at the Whitney through September 20th. It was co-curated by David Kiehl, Curator Emeritus, and David Breslin, DeMartini Family Curator and Director of the Collection.