The Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade Has Strings Attached to the Village

This post is part of our “Beyond the Village and Back” series, in which we look at great New York City landmarks outside of the Village, and trace their (sometimes surprising) roots back to our neighborhood.

On Thursday, November 24, 1927, the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade as we know it was launched. While the first Macy’s parade was held in 1924, it was not until 1927 that Villager, filmmaker, business owner, teacher, children’s book author, and “father of puppetry” Tony Sarg was commissioned to design the parade’s trademark balloons, which remain a staple of the event today, almost a century later.

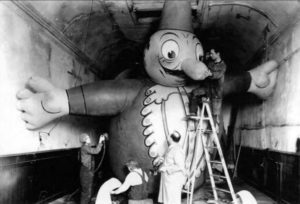

The 1924 parade had little to do with Thanksgiving beyond its timing, instead celebrating Macy’s expansion over the whole city block between Broadway and Seventh Avenue along 34th Street, and anticipating the Christmas season. In addition to featuring floats and an enthroned Santa Claus, Macy’s flaunted Central Park Zoo animals, which the company had rented for the day. However, the creatures proved unruly as the six-mile march progressed, growling at the onlooking crowd. Macy’s determined that the zoo animals had to go and a new, more pleasant plan had to be developed. And so in 1927, Tony Sarg, who spent much of his adult life in Greenwich Village and was already working as the Macy’s parade’s artistic director, introduced his large, rubberized silk puppets, among them Felix the Cat. These first puppets were filled with oxygen rather than helium, and while they were smaller than the balloons we see today, they were still large enough to require that they be propped up by as many as fifty handlers on the ground, most of them Macy’s employees.

In 1928, the balloons were filled with helium and, at the parade’s finale, released into the sky. The next year, the balloons were designed with release valves to facilitate a smoother ascent, and Macy’s offered rewards to those who could find the puppets and bring them back. In 1932, pilot-in-training Annette Gibson attempted to capture sixty-foot Tom the Cat with her biplane when the rubber material perilously caught on her vehicle’s wing. Witnesses watched the plane rapidly fall from the sky, expecting it to crash. Inside the cockpit, however, Gibson’s instructor switched places with her and was able to propel the plane upwards, averting disaster a mere eighty feet from the ground. Afterward, Gibson said, she saw children picking up the pieces of the balloon.

That year, Jerry the pig was picked up in East Islip, Fritz the dachshund was found in the East River, and Georgie the drum major was torn to bits by those who found him in Long Island City. Most likely, this instance of vandalism, in addition to the near-crash, contributed to the screeching halt of the Macy’s competition to find the roaming puppets.

Still, in years when they did not spur such a scandal, Sarg’s puppets generally elicited attention, respect, and admiration. A 1931 New York Times article documented one of many small moments at the parade:

As the 171-foot dragon passed Ninetieth Street a girl, slightly bewildered, looked wonderingly at her mother. As she did so a woman, perhaps too critical, remarked to her companion, ‘Ultramodern, my dear.’

‘Mother,’ the girl asked, ‘what kind of animal is an ultra-modern?’

This charming scene demonstrates how the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade puppets, and Sarg’s work more generally, uniquely sits at the place where high art meets children’s entertainment – and productively confuses the boundary between the two.

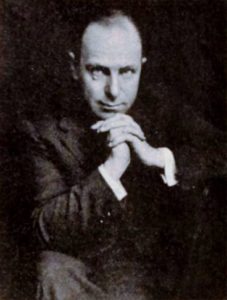

Anthony (Tony) Frederick Sarg (April 21, 1880–March 7, 1942), the man behind the puppets, was born in Guatemala to a German father who worked as a sugar and coffee planter and an artist. His grandfather had trained as a woodcarver, and his grandmother was a collector of marionettes and toys. Sarg spent most of his childhood in Germany, then served in the military before moving to England in the early 1900s, where he worked as a commercial artist for advertising and created a series of posters for the London Underground. Around the start of the First World War, Sarg, his wife, and his daughter faced anti-German sentiment and decided to move to New York, where Sarg worked as an illustrator for the New York Times, the Saturday Evening Post, Colliers, Cosmopolitan, Boy’s Life, and Vanity Fair.

In 1917, Sarg opened the Tony Sarg Company, where Sarg taught puppetry, produced marionette shows, and trained emerging puppeteers including Bill Baird, Margo Rose, and Rufus Rose. Sarg’s classes and the accompanying books and articles he authored were unprecedented and broke open the art of puppetry which until this time was a craft passed down within individual families. In the 1920s, Sarg began working for Macy’s as an artistic director. In addition to the enormous parade puppets he introduced in 1927, Sarg’s legacy lives on today in the nationwide trend of animatronic Christmas window displays, which Sarg developed for the first time for the department store in 1935. It was around this time, in the 1930s, that Sarg moved to 54 West 9th Street in the Greenwich Village Historic District.

Sarg had a prolific and multifaceted career designing children’s barbershops and the toy sections of department stores, as well as textiles, wallpapers, and furniture for children. He owned his own children’s stores in New York and Nantucket, where he had a second home, as well as marionette theaters in New York and Chicago. He is also responsible for creating over twenty animated films and a display at the 1939 World’s Fair. Tragically, Sarg died in 1942 from complications after an appendectomy. Nevertheless, in his relatively short life, he engineered remarkable puppets for all purposes and audiences, he expanded the art and joy of puppeteering, and he transformed Thanksgiving for New York City and for the world at large.

Of course Sarge isn’t the only connection the Macy’s Thanksgiving Parade has to Greenwich Village. Macy’s itself began in 1858 in Greenwich Village on the corner of Sixth Avenue and 14th Street. While that original building has long since been demolished, a slightly later Art Nouveau-influenced Macy’s which dates to 1898 still stands there at 56 West 14th Street — a striking (but often overlooked) building which was landmarked in 2011.

To learn more about the artists who lived and worked in Greenwich Village, see the over one hundred entries in the Artists’ Homes tour in our interactive map Greenwich Village Historic District, 1969-2019: Photos and Tours.

The Sarg story is fascinating beyond its Village connection. Wonderful bit of NY and cultural history. Thank you for a well written informative piece.