Remembering Japanese Internment Through East Village Experimental Theater

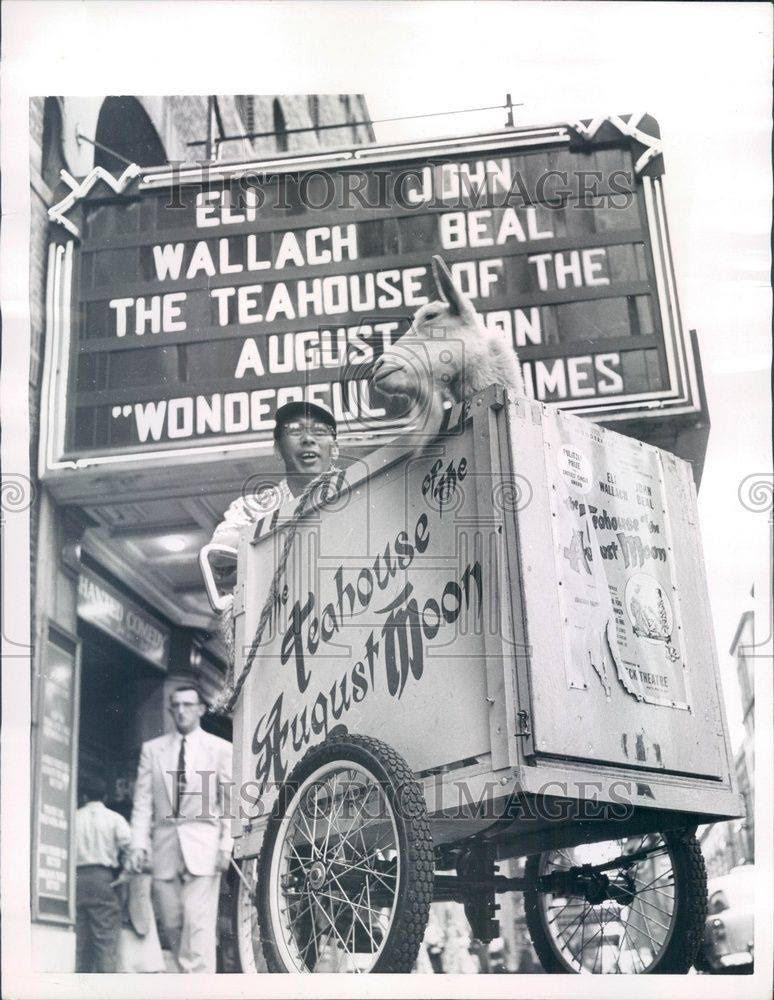

Jerry Fujikawa was a Japanese-American actor who had a long career in films, television, and Broadway. Jerry debuted on Broadway in the five-time Tony Award winning play The Teahouse of the August Moon. He was very a familiar face to film and television audiences whose career spanned over 30 years, including a wide variety of movies, plays, and television shows; Mr. T and Tina, M*A*S*H, and Chinatown were but a few of his most recognizable roles. Jerry was also one of over 110,000 Japanese-Americans interned in camps here in the United States during the course of World War II in response to American hysteria following the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941.

It seems unfathomable that the United States would be the home of internment camps. But on February 19, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the Secretary of War to prescribe certain areas as military zones, clearing the way for the incarceration of Japanese Americans, German Americans, and Italian Americans in U.S. internment camps. Jerry and his young family, along with his parents, his siblings, and their neighbors lost their constitutional rights and were forced to relocate to the Manzanar Camp in California in 1943. Most remained there until 1945.

Cynthia (Cyndy) Gates Fujikawa, Jerry’s daughter by a second marriage, followed in her father’s footsteps by becoming an actress herself. Cyndy’s pursuit of a career in the theater lead her from California to New York in the 1990’s. Very shortly after her arrival, Cyndy began developing a one-woman play based upon her father’s life, his incarceration at Manzanar, and her quest to uncover the story of his mysterious first family and the search for a long-lost sister she never knew she had. Her submissions process brought her to Mabou Mines, an artist-driven, experimental East Village theater collective generating original works and re-imagined adaptations of classics. Work at Mabou Mines is created through multi-disciplinary, technologically inventive collaborations among its members and a wide world of contemporary filmmakers, composers, writers, musicians, choreographers, puppeteers, and visual artists. Mabou Mines fosters the next generation of artists through mentorship and residencies, and remains a leading light in nurturing a variety of artistic voices at artistic home at PS122. Cyndy found herself embraced by the company and was given the space and mentorship to create her work through an extended development process with the Mabou Mines Resident Artists Program.

Lee Breuer served as Cyndy’s artistic mentor and Ruth Maleczech was her guiding light and champion of the project. The result of Cyndy’s quest is a beautiful and searing autobiographical account, called Old Man River, of uncovering a father very different from the one she thought she knew; a man whose life was destroyed by his internment.

In Cyndy’s words about her experience:

“I had written a short story called OLD MAN RIVER, which was, in my head, my dad’s anthem: a classic song he couldn’t sing, but would continually attempt. One day, I listened to the lyrics and made the connection between his life and the song. That was the beginning of the road. Where I went from there was an odyssey. My half sister, Tirsa, had been missing since 1946.The subject of her had been off limits for years, but I had made attempts to track her down, with no luck. In 1993, that changed. I found Tirsa after an exhaustive search and the story of my dad became my story, and I documented every step.

I had just three meetings with Lee Breuer, but the one I remember was him comparing me to another one man show which dealt with racism. It was a wonderful piece, written by an African American male, but it was a bit more artsy. “He’s is a pussy. You’re a tiger.” Lee repeated “You’re a tiger.” Such a simple piece of advice. I still bear it in mind to this day.

But Ruth Maleczech was definitely the force behind this program. She lead our bi-monthly meetings and spoke up. She didn’t tip her hand, but you could tell she cared deeply about new works and about giving the artists their space to make their voices heard. My pages – all 200 of them – were very raw. And although she referred to my script as “a book” she never stopped me from trying all 2 hours and 15 minutes (plus intermission) in front of an audience at PS122.

For my part, I was working on not just the story of my dad, but how it fit into our national amnesia and ignorance of the Japanese American experience. Ruth recognized the need to tell this story.

Ruth invited artistic directors and literary managers from other East Village theatre companies to see my monologue, including folks from the Public Theatre and New York Theatre Workshop (the latter scooped me up into stage 2 of development, and a few weeks later I was on a NYTW artist retreat with Jonathan Larson, Ain Gordon, Jefferson Mays, and many other amazing artists on the verge).

And don’t forget…the online archives and personal histories that would inform a project like Old Man River just didn’t exist in 1995! Along with my friend — researcher and visual consultant Jill Cornell — we ripped very low res photos from a handful of library books for the multi-media component, and dug into our family stories for knowledge. Our difficulty in finding source material was woven into the story. I believe that our work was a pioneer for many subsequent shows on the subject. This information is now at our finger tips for those who are curious. But it started with the witness telling her story; stories that were not easily pried out of our aunts and uncles. I credit PS122 and Mabou Mines for recognizing the the subject matter, and giving it voice, stage time, and the writer/performer a place to work, research, fail and succeed.

Having a physical space, and the umbrella of Mabou Mines at PS122 (then called Mabou Mines Suite) anchored each of our projects and breathed life into our plays. I remain so grateful to Mabou Mines for the opportunity and I recall fondly on the days I would traipse downtown to PS122, unlock the door, and explore the work with my friends and fellow artists.”

Mabou Mines continues to nurture new voices in the theater through the RAP, which offers emerging artists the opportunity to work in residence for six months and helps them breathe life into their works, as they did with the work of Old Man River.

Because February 19th is the day President Roosevelt signed the order mandating Japanese internment, it is now known as “The Day of Remembrance.” In keeping with remembrance, it is fitting to note here two Japanese-American visual artists who were residents of our neighborhoods and suffered through internment: Mine Okubo, who resided at 17 East 9th Street, and Isamu Noguchi, who from 1942 until the late 1940’s lived and worked at 33 MacDougal Alley.

For many years, Mine Okubo was interned at Tanforan and later at Topaz, following President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066. She is best known for her 1946 book Citizen 13660, in which she recounts her experiences at Tanforan and Topaz. Citizen 13660 was one of the first widely-circulated personal accounts of the repression and indignities faced by the interned.

Okubo documented her experience at the camp in her sketchbook, recording images of the humiliation and everyday struggle of internment. In time, Fortune magazine learned of her talent and offered her assignments. When the War Relocation Authority began allowing people to leave the camps and relocate in areas away from the Pacific Coast, Mine took the opportunity to move to New York City, where Fortune was located. Upon her arrival, she moved to 17 E 9th Street. It was here that she completed her work on Citizen 13660, named for the number assigned to her family unit, containing more than two hundred pen and ink sketches. Citizen 13660 is considered a classic of American literature and a forerunner of the graphic novel and memoir.

Noguchi, the son of an Irish-American mother and Japanese father, was one of the 20th century’s most important and critically acclaimed sculptors. He was also an outspoken advocate against the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II, and though he could have avoided internment himself, was voluntarily interned in a camp for seven months. From 1942 until the late 1940’s Noguchi lived and worked at 33 MacDougal Alley, which was soon after demolished to make way for the high-rise apartment building at 2 Fifth Avenue

On this Day of Remembrance, I would like to invoke an adage that I think about a great deal these days: “Those who do not remember their past are condemned to repeat their mistakes.” We remember and we honor those whose lives were inexorably altered by their experiences in the wars of the world.