Greenwich Village Folk Recording Released 58 Years Later by Smithsonian

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings recently released an album by Doc Watson and Gaither Carlton of old-time music produced from archival recordings by two legendary musicians performing live in Greenwich Village. These largely unheard tapes were recorded at Doc Watson’s two earliest concerts, in 1962. Those shows were among the rare appearances of Doc’s father-in-law and fiddler Gaither Carlton ever made outside of North Carolina. You can learn more and order it here.

On the songs and ballads, Doc’s readily recognizable baritone voice is accompanied by his own guitar and Gaither’s fiddle, or by the traditional combination of fiddle and banjo. Shortly after these recordings in Greenwich Village were made, Doc Watson embarked on a career as one of America’s premier acoustic guitarists, earning the National Medal of Arts and numerous Grammy Awards.

Born Arthel Lane in 1923 in Deep Gap, North Carolina, “Doc” lost his sight by the age of two. The virtuosos guitarist got his nickname from Sherlock Holmes’ partner. His father made him his first banjo out of cat skin, not unique at the time. The Smithsonian recordings come from two different concerts in the Village from October 1962. One performance was sponsored by the Friends of Old Time Music at NYU School of Education and held in the auditorium at 35 West 4th Street.

Tickets for $1.75 were available at the Folklore Center then at 110 MacDougal Street.

The other recording was from a performance at the Blind Lemon folk club in the West Village. According to an interview with Peter Siegel by Elliot Sharp in Premier Guitar:

After Doc Watson’s FOTM concert, Doc and [fiddle and banjo player] Gaither Carlton stayed in New York City an extra week. So there was a club on Sullivan Street between Bleecker and 3rd called Blind Lemon’s that was open for just like two weeks. [Folksinger and musicologist] Ralph Rinzler was friends with whoever had it, and they arranged for Doc and Gaither to play this gig for one night. Those are the tapes I’m now working with. Doc was singing beautifully.

Siegel refreshed his memory and confirmed in an email the address memory of exactly where on Sullivan Street the shortlived Blind Lemon was located (just north of West Houston Street). It was also noted in The Conscience of the Folk Revival: The Writings of Israel “Izzy” Young by Scott Barretta that the club was at 169 Sullivan Street.

In a personal email Peter Siegel mentioned some charming aspects of that very evening, recorded for posterity:

“…it was at street level. One of the things I remember was an old time cash register, which you can hear on the recordings (as well as a contemporary phone ringing) and a classic brass espresso machine. I think I remember those things because they made noises that, to my dismay, were going on the tape. Today those artifacts sound more charming.”

Doc Watson was playing near his home in tiny Deep Gap, North Carolina when he was “discovered” by folklorist Ralph Rinzler. It was Peter Siegel, who founded the Nonesuch Explorer Series, who recorded the historic concerts in New York.

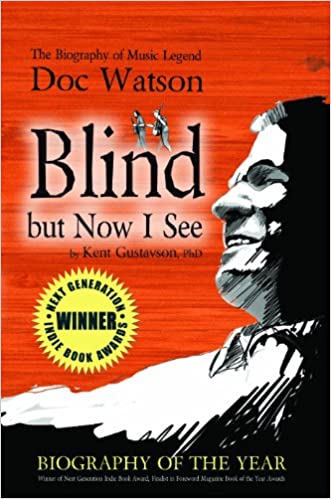

by Kent Gustavson

A Definitive Biography of an American Icon

The recordings feature Watson on guitar, banjo, autoharp and singing with Carlton on fiddle and banjo and it has some songs from the Friends of Old Time Music show from Friday, October 12 at NYU School of Education. The rest of the music is from October 18 at Blind Lemon’s, NYC. These recordings include songs the pair later played at the Newport Folk Festival.

It was in Greenwich Village that Doc Watson met legendary musician Mississippi John Hurt while he played with Tom Paxton for a run at the Gaslight cafe. According to Paxton:

“Bob Dylan, Dave Van Ronk, Patrick Sky and Phil Ochs, to name just a few, got to hear him three or four times a night and we all just soaked up that music by osmosis… It was during that short run at The Gaslight that John met Doc Watson and the two of them became instant buddies. To see this little black man from the Delta and a blind white man from the mountains of western North Carolina chatting and chuckling was really something for those days.”

Michael J. Kramer has an intriguing essay called When Mississippi John Hurt’s Head Moved.