Paulo d’Angola: the Former Slave Who Became One of Greenwich Village’s First Landowners

Paulo d’Angola came to New Amsterdam on the first ship bringing enslaved people to this region in 1626. Nearly twenty years later, d’Angola and others in this group successfully petitioned the Dutch West India Company for their freedom. Then, on July 14, 1645, d’Angola was granted a six acre plot of farmland in and around what is today Washington Square Park. While several other formerly enslaved individuals won their freedom and these land grants in the weeks and months before him, most of the land they were given was a bit further south, in what would today be called the Lower East Side, SoHo, and Tribeca. This made d’Angola the very first non-Native American settler in the heart of what is today Greenwich Village. His story is part of a critical, but largely forgotten, history of enslavement and early Black land ownership in our neighborhoods.

According to historian Christopher Moore, the first free Black community settlement in North America developed in Lower Manhattan, in an area that includes much of present-day Greenwich Village and the East Village. This settlement, sometimes referred to as “The Land of the Blacks,” was divided into individual landholdings, many of which belonged to people formerly enslaved by the Dutch West India Company. These early New Amsterdam landowners, both men and women, had been manumitted as early as within twenty years of the founding of New Amsterdam.

Like d’Angola, many of them were among the very first Africans brought to New Amsterdam as enslaved people in 1626, two years after the colony’s founding. Those who arrived on that first ship, including d’Angola, were originally from Congo, Angola, and the island of São Tomé, as reflected in the names they were given. Enslaved by the Dutch West India Company, they lived at the Saw Mill, in a camp called Quartier van de Swarten (Quarters of the Blacks) located along the East River by today’s 75th Street.

On February 25, 1644, several of these individuals petitioned the Dutch authorities for “half-freedom.” In return, they were granted parcels of land by the Council of New Amsterdam, under the condition that a portion of their farming proceeds go to the Dutch West India Company. Although Director General William Kieft offered land under the guise of a reward for years of loyal servitude, these particular parcels of land may have been granted by the Council, at least in part, for more calculated reasons.

The farms provided lay between the settlement of New Amsterdam on the southern tip of Manhattan Island and areas controlled by Native Americans to the north. Native Americans sometimes raided or attacked the Dutch settlement, and it is possible that the Council hoped to create a buffer between these two areas by giving land to the formerly enslaved individuals. Nevertheless, some scholars have noted that this area was among the most desirable farmland in the vicinity. The Dutch Governor Peter Stuyvesant established his own farm here in 1651.

From 1643 until 1716, about thirty land grants in New Amsterdam were owned by free Black men and women. Other landowners who were part of this community included Catalina Anthony, Domingo Anthony, Cleyn (Little) Manuel, Manuel de Garrit de Rues, Manuel Trumpeter, Widow Marycke, Gracia d’Angola, Simon Congo, Jan Francisco, Pieter San Tome, Manuel Groot (Big Manuel), Cleyn (Little) Anthony, Jan Fort Orange, Anthony Portuguese, Anna d’Angola, Francisco d’Angola, Anthony Congo, Bastiaen Negro, Jan Negro, Manuel the Spaniard, Mathias Anthony, Domingo Angola, Claes Negro, Assento Angola, Francisco Cartagena, Anthony of the Bowery, Anthony the Blind Negro, and Manuel Sanders. Their collective landholdings covered the area from the Bowery Road by the Collect Pond (near today’s Canal Street) to Fifth Avenue and 34th Street. Paulo d’Angola owned a portion of property from Minetta Lane to Thompson Street.

The status of the free Black settlement was not permanent, however. When the English captured the colony of New Amsterdam and renamed it New York in 1664, the newly established English government stripped free Black people of landowning rights and established strict and complex enslavement codes. By 1712, colonial New York law fully prohibited Black land ownership through both purchase and inheritance, denying free Black people all landowning rights and privileges. Within twenty years, the vast majority of land owned by people of African descent was seized by wealthy white landowners who turned these former free Black settlements into retreats, farms, and plantations.

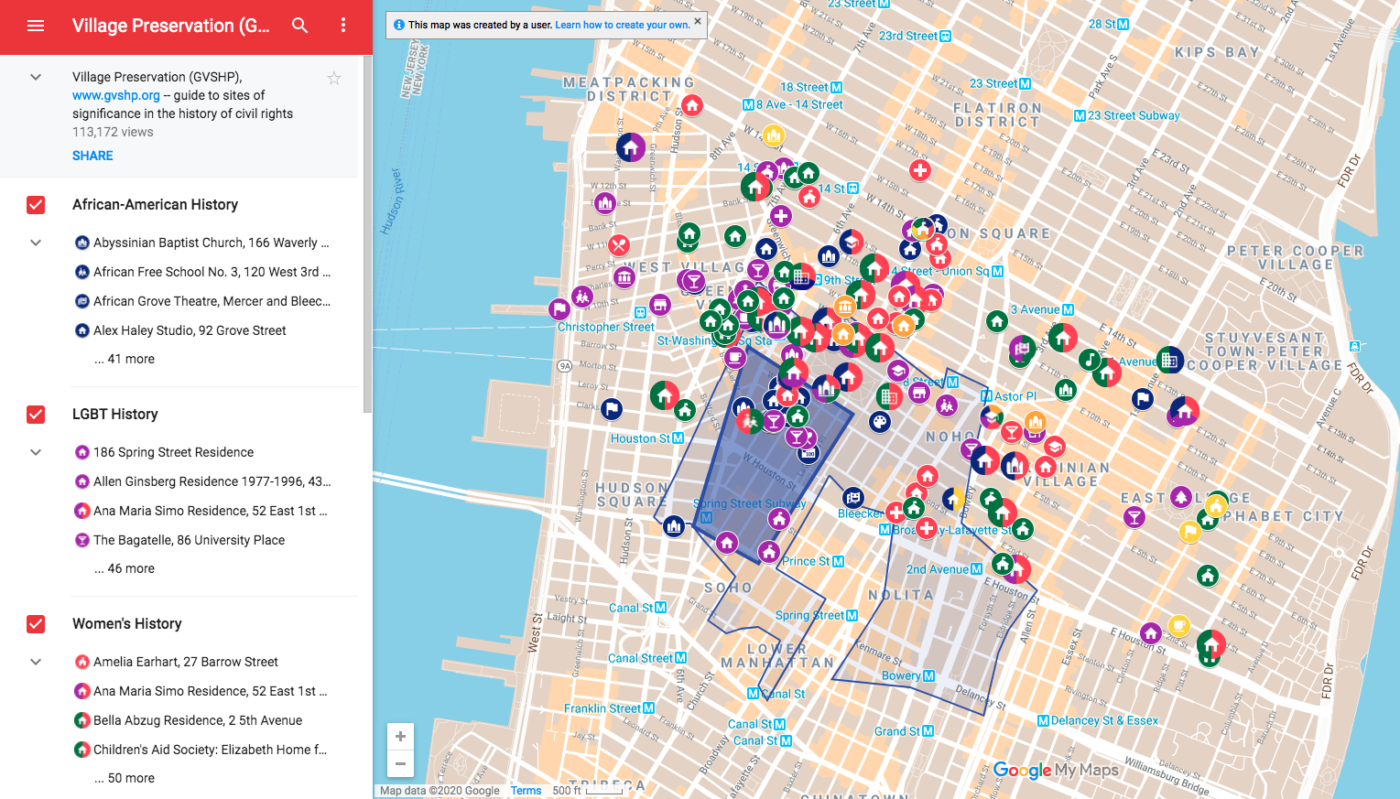

The remarkable story of Paulo d’Angola, and the community of Black landowners of which he was a part, is an essential part of Black history in our neighborhoods, New York City, and the country at large. For more information please see the African American History tour on our interactive map Greenwich Village Historic District: Then & Now Photos and Tours and our Civil Rights and Social Justice Map.

Sources:

“Black New Yorkers” by The Schomburg Center

The iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498-1909 (v. 6), by I.N. Phelps Stokes

There was a period in, essentially, pre-colonial times, when slaves were a product of conquest, regardless of skin color. Colonial times were dominated by the British. Under the British, skin color seems to have become a definitive part of slavery.

How does this relate to the history of New World slavery in areas controlled by the Spanish and Portuguese empires?

I have never had the privilege of spending some hours at the Schomburg Center. That is now high on my list of todos as soon as I am able to do so.

I think there is a mistake in here…. Should be Peter Stuyvesant and not Peter Amsterdam.

Fixed this, thank you.