Rose Schneiderman: Making History at the Intersection of Labor and Women’s Suffrage

A remarkable number of people and places in Greenwich Village, the East Village, and NoHo played important roles in the move towards women’s suffrage. These neighborhoods were long centers of political ferment and progressive social change, and women and men here played a prominent part in removing barriers to women voting in New York State (which didn’t grant women the right to vote until 1917) and the country. In honor of the centennial of the passage of the 19th Amendment, Village Preservation has created a StoryMap that chronicles the impact our neighborhoods and its residents had to ensure the right to vote for women.

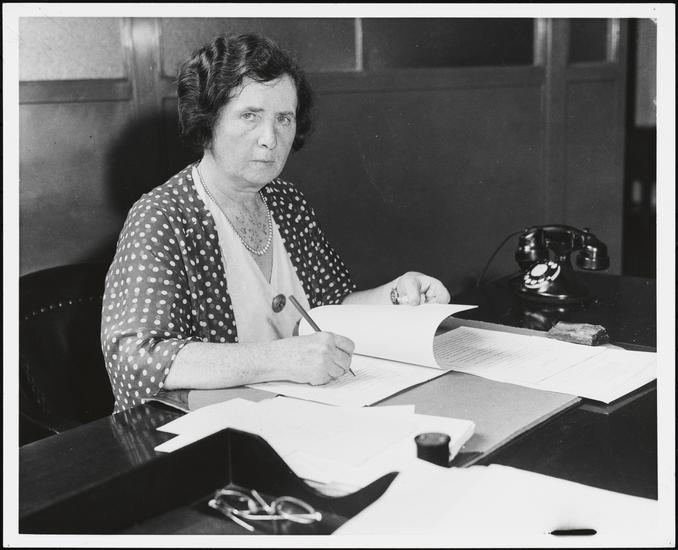

Today, we highlight one of the entries from our StoryMap, Rose Schneiderman, the first woman voted into national office in any American labor organization, and an outspoken suffragist.

ROSE SCHNEIDERMAN — 57-59 SECOND AVENUE

A resident at 57-59 Second Avenue, suffragist Rose Schneiderman was an essential player in the New York Women’s Trade Union League (NYWTUL) for thirty-five years. She organized the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union from 1909 to 1914, and the 1909 Shirtwaist Strike. In 1911, she participated in founding the Wage Earner’s League for Woman Suffrage and promoted the Ohio suffrage referendum in 1912. A key player in New York’s suffrage movement, Schneiderman is one of many who spoke on the subject at ht he rallies and meetings called at Cooper Union. She is famous for saying “What the woman who labors wants is the right to live, not simply exist — the right to life as the rich woman has the right to life, and the sun and music and art. You have nothing that the humblest worker has not a right to have also. The worker must have bread, but she must have roses, too.”

Born in Saven, Poland on April 6, 1882, Rose Schneiderman’s parents, Samuel and Deborah, were tailors. They insisted that Rose go to school, which she did in both public and Jewish institutions. In 1890, the family moved to New York City, and in 1892, Samuel died. Rose was sent temporarily to an orphanage, while her mother struggled to find work that could support the family. At thirteen, Rose joined the workforce. These experiences no doubt informed Rose’s later passion and activism for feminism and labor.

Schneiderman worked in retail sales for three years, but her low salary pushed her into the harder factory work of cap making. We know that factory women were still paid low wages, and were endangered by poor working conditions. Schneiderman became interested in the labor movement as a solution for the working class, and so she organized her workplace into a branch of the United Cloth Hat and Cap Makers’ Union. From such a small woman came powerful oration, and Schneiderman soon became the first woman voted into national office in any American labor organization.

Schneiderman led strikes at her job, and through that work became involved with the New York Women’s Trade Union League (NYWTUL), founded by middle-class women to help working women unionize. By 1906, she was vice president of the NYWTUL. As Vice President, Schneiderman was given a stipend which allowed her to work full-time as the union’s East Side organizer.

In 1908 she began working as the League’s chief organizer specializing in garment workshops. Schneiderman’s organizing work helped set the stage for the “Uprising of the 20,000,” sparked by East Villager Clara Lemlich. That 1909-1910 general strike by garment workers — most of whom were young women — had many concrete results, along with the incalculable ripples that were the result of its powerful magnitude.

Schneiderman was also an influential figure in the activism following the tragedy of the Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire, which killed 146 garment workers (mostly young immigrant women) on March 25, 1911. The fire, and all the negligence and mismanagement that created the conditions for the fire, caused widespread grief and outrage, in addition to galvanizing labor movements to push for real, systemic change.

According to the Jewish Women’s Archive, in a speech Schneiderman gave at a meeting protesting the fire, “[she] expressed her anger that the lives of working people were not valued more and held citizens accountable for the poor conditions of workers’ lives. Responses to the fire such as Schneiderman’s led to the creation of more effective fire and safety regulations for the workplace.”

In the years before the 19th Amendment passed in 1920, Schneiderman played a key role in the New York State suffrage campaign. In 1920, she ran for the U.S. Senate as a member of the Labor Party, bringing well-needed attention to her labor movement’s agenda and the needs and rights of working people. This gave Schneiderman a kind of national notoriety, and brought her into contact and friendship with another Villager, Eleanor Roosevelt. As such, Schneiderman became the only woman at the time to serve on the National Labor Advisory Board, helping to shape New Deal legislation. In 1937, she became Secretary of Labor for New York State. An incredible journey for a young Jewish immigrant from Poland.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Schneiderman got involved in the American Jewish efforts to rescue Jewish refugees from Europe.

Schneiderman never married, but we know that she had relationships with several other prominent women she encountered and worked with thorugh her labor organizing. She died in 1972, at age 90.

Rose Schneiderman is just one of over two dozen people, places, and organizations featured on our 19th Amendment Centennial StoryMap, including activists, labor organizers, and religious leaders including former First Lady and First Daughter Margaret Woodrow Wilson, Chinese-American teenage suffrage and civil rights activist Mabel Ping Hua Lee, and three of our country’s most renowned abolitionists connected to the Mother Zion AME Church, which was located in Greenwich Village in the late 19th century. Want to find out more? Explore our interactive map further!