Angel Hair Press: “A Rush of Poetic Chutzpah” in the East Village

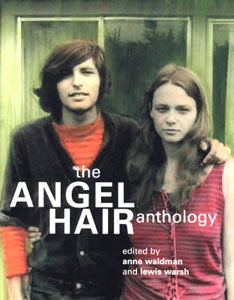

The poets and New York natives Anne Waldman and Lewis Warsh met at the Berkeley Poetry Conference in 1965, while absorbing the Zen-influenced poems of San Francisco-based writer Robert Duncan. This chance encounter begat a romantic and creative partnership that, back across the country in the East Village, lit a spark within the Downtown poetry scene. Lewis remembers: “we were going on nerve, all of twenty years old, but trusting in our love, which was less tricky and in the moment defied all uncertainty.” Angel Hair, the beloved yet short-lived magazine and small press, was, he says, “our way of giving birth — as much to the actual magazine and books as to our selves as poets.”

Lewis had graduated from the New School and was based in Manhattan; Anne, after finishing her undergraduate degree at Bennington College in Vermont, joined him in the East Village. Anne recalls in the introduction to Granary Book’s Angel Hair anthology titled Angel Hair Sleeps with a Boy in My Head: “here was a fellow New Yorker, same age, who had also written novels, was erudite about contemporary poetry. Mutual recognition lit us up.” She had written stories, plays, and “ee-cummingesque poems in high school,” submitting them to publications like the Village Voice with little luck. Anne had also met, and been greatly inspired by, the late Diane di Prima at the Albert Hotel, a legendary artists’ residence in Greenwich Village.

The first print run of Angel Hair, in its first incarnation as a literary magazine, cost $150 to print. It was printed with leftover materials from SILO, the literary magazine that a younger Anne had edited during college. The duo sent out the magazine to “a range of family, friends, poets, other folk, receiving back modest support.” Angel Hair ran six magazine issues; the poets then began publishing the work of their fellow poets in book form, using mimeograph, offset, and occasionally letterpress printing. The first book they published, Lee Harwood’s The Man with Blue Eyes, was released on January 1, 1966. “Each book had its own reality,” Anne said, “we were making [it] up on the spot, stumbling along improvisationally.”

Anne and Lewis were living at 33 St. Marks’ Place, between Third and Second Avenues in a “skinny railroad apartment,” which, as Lewis notes in one interview, is now a body piercing shop. Their rent was $110 a month. After Angel Hair’s debut, the space was transformed into what Anne describes as a “veritable salon” for the poets, writers, and fellow travelers of the downtown scene. “The cranky lady next door,” she recalls, “often called the police as decibels mounted.” Friend and collaborator Ted Berrigan, who lived on Second Street between Avenues C and D, was a mainstay at these parties. Friends of the Velvet Underground and Andy Warhol were in attendance, and after the night’s festivities subsided, Anne and Lewis would stay up working on Angel Hair until sunrise. After dawn, they might spot their neighbor W.H. Auden out the window, taking his morning constitutional.

Anne was recently employed as an assistant at the newly formed arts organization the Poetry Project, located at St. Marks’ Church-in-the-Bowery. (The Project is still alive and well and, as many blog readers may be aware, is Village Preservation’s neighbor at the church’s former rectory). The Wednesday night readings at the Project brought huge spillover crowds into the 33 St. Mark’s apartment. Poet Barbara Guest writes in the spring 1968 edition of Angel Hair Magazine, evoking this revelry: “we had a secret/ (able to live gracefully/ in tenements)… no longer/’traditional’ or ‘isolated.'”

At this time, remembers Anne, “St. Mark’s [Place] was a hotbed of anti-Vietnam War political activity.” Scholar Daniel Kane writes: “as the East Village from 1966 to the early 1970s found itself home to the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church, the Kerista free-love movement, the predominantly Latino Young Lords self-help organization… the Bowery Poets Coop, the Filmore East performance space, the East Village Other, and dozens of other countercultural ‘institutions,’ the poems in Angel Hair served as lyrical counterparts to communitarian radical organization.” As an example of Angel Hair’s countercultural verse, Kane offers Jack Anderson’s “American Flag:” “The American flag/ is being set on fire. The match touches, first one stripe, / then the rest…. The reason why the American flag has been set on fire is to/ protest American policies regarding the Vietnam War.”

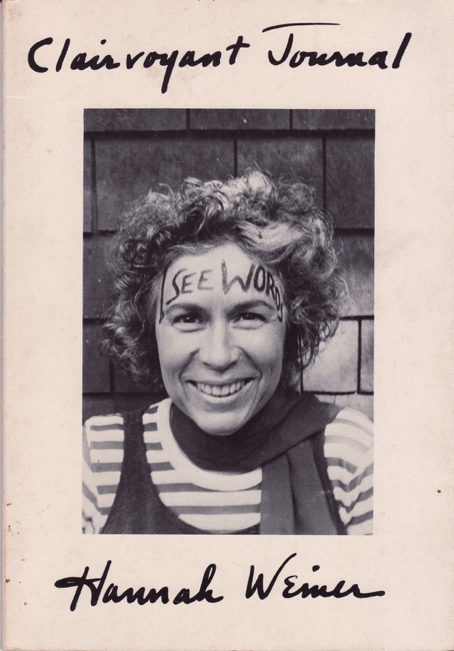

The production of Angel Hair and its communitarian, neighborhood-informed sensibilities provided, as Kane suggests, a “metaphoric parallel” to the already-radical nature of the East Village. It gave young poets the knowledge, Anne says, “that you can take your work, literally, into your own hands. You don’t have to wait to be discovered.” Its values of friendship, artistic collaboration, and do-it-yourself ethos, characterized this so-called “second-generation New York School,” and the successive L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E Poetry movement of the 1970s. Along with six magazine issues, Angel Hair published such influential works as Bernadette Mayer’s Eruditio Ex Memoria, Moving, and The Golden Book of Words; Joe Brainard’s I Remember, and Hannah Weiner’s Clairvoyant Journals — over 35 books and broadsides total. When Angel Hair’s publication of Ted Berrigan’s The Sonnets was picked up by Grove Press, the pair and their friends “celebrated all week.”

Testifying to Angel Hair’s legacy, Anne said: “A major consequence of Angel Hair’s publishing debut books and pamphlets and other items was the launching of an array of young experimental writers, including ourselves, onto the scene and into the official annals as second-generation New York School poets. In retrospect Angel Hair seems a seed syllable that unlocked various energetic post-modern and post-New American Poetry possibilities.” “So-called ephemera,” she concludes, “lovingly and painstakingly produced, have tremendous power.” Journalist Tysh George characterized the literary endeavor as a “rush of poetic chutzpah… The New York Poets are in love with life and its words. Like Walt Whitman, their illustrious progenitor, and the city they call home, these impetuous wordiacs embrace it all.”

In the summer 1967 edition of the magazine, Robert Duncan recalls the serendipitous day that gave birth to Angel Hair. He writes in “At the Poetry Conference: Berkeley After the New York Style,”

“I put the coda towards the last

for friendship’s sake

Envoys and buses O’Hara needed

To get where I am behind time and scenes

[Do this passage in a BIG VOICE]

The audience is crowding in

To hear what we need and is lovely.”

In Lewis Warsh’s memory, The Poetry Project has collected a series of texts and remembrances on the poet’s life and work, available here.

Anne Waldman is one of among many creative luminaries featured in Greenwich Village Stories, edited by Judith Stonehill in collaboration with Village Preservation, available here.

You can learn more about significant sites in the East Village, through our interactive resource, East Village Building Blocks.

2 responses to “Angel Hair Press: “A Rush of Poetic Chutzpah” in the East Village”