The Birth of the NAACP, and Their Deep Roots in Greenwich Village

For over 100 years, the NAACP has been fighting to ensure the political, educational, social, and economic equality of rights of all persons, and to eliminate race-based discrimination. Though their headquarters is now located in Baltimore, Maryland, the organization called our neighborhood home for decades, and held its first public meeting here as well. Founded on February 12, 1909, the 100th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth, any time is a good time to highlight their history and their profound connections to our neighborhood.

The Race Riot of 1908 in Springfield, Illinois, the state capital and President Abraham Lincoln’s hometown, was an explosive catalyst in revealing the urgent need for an effective organization advocating tot the civil rights of African Americans in the United States. During the first decade of the 20th Century, the rate of lynchings of African Americans, particularly men, was at an all-time high. Suffragist Mary White Ovington, journalist William English Walling (the wealthy Socialist son of a former slave-holding family), and philosopher Henry Moskowitz met in New York City in January of 1909 to work on organizing for black civil rights. They sent out solicitations for support to more than 60 prominent Americans, and set a meeting date for February 12, 1909. While the first large public meeting did not take place until three months later, the February date is cited as the founding date of the organization.

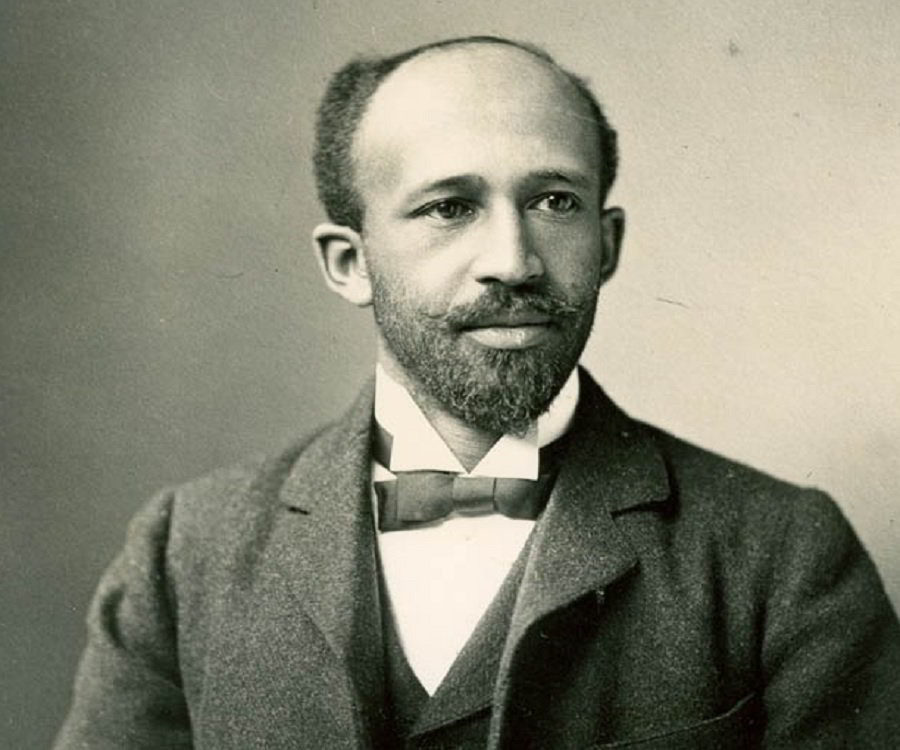

The founding group of the NAACP, was, officially, a much larger group and included African Americans W. E. B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells, Archibald Grimké, Mary Church Terrell, Florence Kelley, Oswald Garrison Villard, and Charles Edward Russell (who was a renowned muckraker and close friend of Walling). On May 30, 1909, the Niagara Movement conference took place at New York City’s Henry Street Settlement House and the predecessor to the NAACP, the National Negro Committee, was born, with lawyer Moorfield Storey serving as its first president. During the next year, they would hold five conferences, including their first public meeting at Cooper Union in the summer of 1909, eventually incorporating as the “National Association for the Advancement of Colored People” in 1910. Du Bois himself played a key role in organizing and presided over the proceedings. Ida Wells addressed the conferences on the history of lynching in the United States and called for action to publicize and prosecute such crimes.

The NAACP would soon find a more permanent home nearby in our neighborhood. The striking 12-story Beaux Arts style office building at 70 Fifth Avenue was constructed in 1912 by architect Charles Alonzo Rich for the noted publisher and philanthropist George A. Plimpton. Other than minor ground floor alterations, the building’s original century-old design is almost entirely intact. Shortly after it opened, the NAACP, as well as Du Bois’ journalistic endeavors The Crisis (the very first magazine dedicated to African Americans, and still printed today) and DuBois and Dill Publishing, called this their home. This was a time of extraordinary growth, accomplishment, and challenges for what would become our nation’s oldest and largest civil rights organization.

During the NAACP’s time at 70 Fifth Avenue, the status of civil rights for African Americans was arguably deteriorating in many ways. States were introducing legislation to ban interracial marriages and formalize barriers to voting and access to housing. In 1913, President Woodrow Wilson introduced segregation into federal government agencies, establishing separate workplaces, bathrooms, and lunchrooms for blacks and whites. Among the NAACP’s first campaigns while at 70 Fifth Avenue was to challenge the newly-instituted segregation within the federal government with a highly-publicized “Open Letter to President Wilson.” At this time, the NAACP also succeeded in securing the repeal of an American Bar Association resolution barring the admission of black lawyers, as well as in the opening of the women’s suffrage parade in Washington D.C. to black marchers.

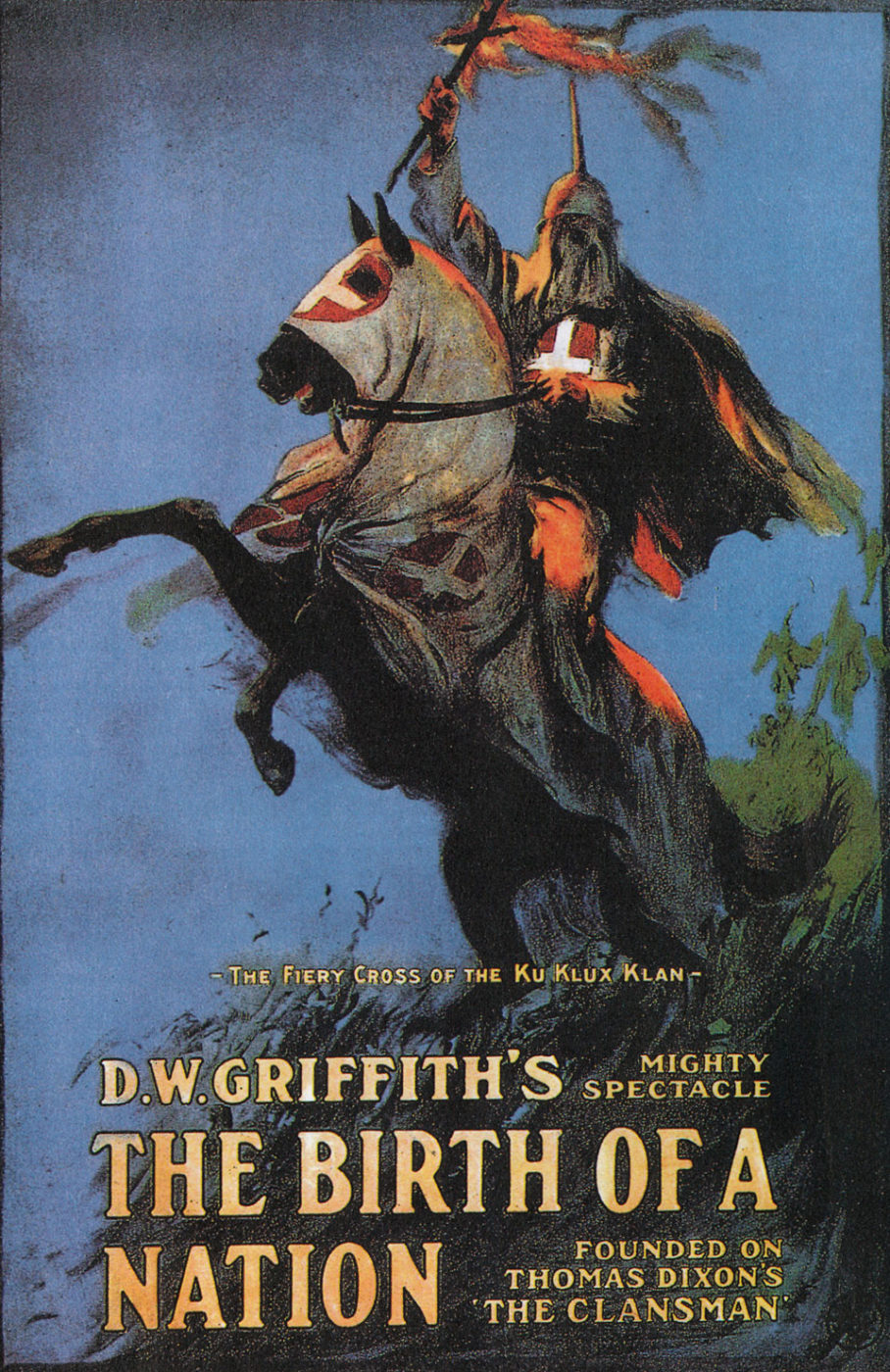

In 1915, their second year in the Village, the NAACP launched its campaign against D. W. Griffith’s film The Birth of A Nation, arguing that it distorted history and slandered the entire black race. The wildly successful film was credited with the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan (also inspiring their use of burning crosses) and an increase in violence against African Americans; its prominence was raised by being shown at the White House by President Woodrow Wilson, the first film showing ever in the presidential residence.

Later that same year, the NAACP participated for the first time in litigation to advance its agenda – just the beginning of a storied history of changing the national landscape through the courts, which of course included the landmark Brown vs. Board of Education Supreme Court decision in 1954, eventually ending legal segregation and the doctrine of “separate but equal” in this country. Moorfield Storey successfully argued the case of Guinn vs. U.S. before the Supreme Court, striking down a “grandfather clause” in the Oklahoma Constitution which effectively barred most black men from voting by limiting the franchise to literate men or those whose ancestors were eligible to vote before January 1, 1866.

In 1916, the NAACP responded to the mutilation, burning, and lynching of an illiterate 17-year-old black farmhand in Waco, Texas accused of raping and murdering a white woman. Labeled “The Waco Horror” by the NAACP, the organization sent an investigator to Texas whose report, including pictures of the horrifying act, was published in their newspaper and distributed not only to the magazine’s 42,000 subscribers, but 700 white newspapers, members of congress, and affluent New Yorkers in an effort to gain support for their newly established anti-lynching fund. The NAACP’s anti-lynching organizing brought national attention to the oft-overlooked crime and mobilized political and business leaders in both the north and south to speak out against this de facto state-sanctioned domestic terrorism

In 1917, following the brutal East St. Louis race riots in which between 40 and 250 African Americans were killed, thousands were made homeless from the burning of their homes, and thousands eventually left the city, the NAACP organized a silent protest down Fifth Avenue of nearly 10,000 African American men, women, and children. They marched to only the sound of muffled drums, carrying signs with messages such as “Thou Shalt Not Kill,” “Make America safe for democracy” and “We march because we want our children to live in a better land.” This was the first protest of its kind in New York City, and only the second instance of African Americans publicly demonstrating for civil rights.

In 1918, the NAACP secured passage of an amendment to the New York State Civil rights law protecting African Americans, their first such statewide success which they used as a model for progress in other states in subsequent years. After bitter resistance, the NAACP also finally secured from President Woodrow Wilson a public pronouncement against lynching, which he had previously refused to do. That same year, an anti-lynching bill was introduced in the House based on a bill drafted by NAACP co-founder Albert E. Pillsbury. The bill called for the prosecution of lynchers in federal court and made state officials who failed to protect lynching victims or prosecute lynchers punishable by up to five years in prison and a $5,000 fine. It also allowed the victim’s heirs to recover up to $10,000 from the county where the crime occurred.

In 1919, the NAACP released its landmark report “Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States, 1889-1918,” in which it listed the names of every African American, by state, whom they could document had been lynched. This continued to bring unprecedented attention to this longstanding and uncontrolled epidemic of violence in America. In the aftermath of the end of the First World War and the subsequent unrest and intolerance which gripped the nation, 26 race riots erupted across the country during that “Red Summer,” and a record number of lynchings took place. Membership in the NAACP grew to about 90,000.

Multiple accounts also say that the NAACP began flying its iconic flag printed with “A Man Was Lynched Yesterday” in simple white sans-serif letters against a plain black background from its headquarters in 1920. While the sole photographic record of this appears to be an image from 1936 when the flag flew from their next location just up the street at 69 Fifth Avenue (demolished), if this frequently-cited date is correct, then this powerful campaign began at 70 Fifth Avenue.

In 1922, the anti-lynching legislation was finally approved by the House by a vote of 230 to 119, after a vigorous campaign by the NAACP which included newspaper ads across the country entitled “The Shame of America.” While the bill died in the Senate after a filibuster by Southern Democrats, congressmen in New Jersey, Delaware, Michigan, and Wisconsin who voted against the measure were defeated in the election of 1922 after their stance was made an issue in their campaigns.

In 1923, the NAACP had another successful case before the U.S. Supreme Court when they appealed the convictions of 12 African American men sentenced to death and 67 to long prison terms by an all-white jury. Those sentences had resulted from bloody riots in Arkansas in 1919 precipitated by a white mob attacking a mass meeting of black farmers trying to organize a union, in which as many as 200 blacks and 20 whites were killed. In Moore v. Dempsey, those convictions were overturned, ruling that the defendants’ mob-dominated trials were a violation of the due process guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. The landmark decision reversed the court’s previous ruling in the 1915 case of Leo Frank, a Jewish man convicted of murdering Mary Phagan, a 13-year-old employee of the Atlanta pencil factory that he managed, on specious evidence in what was widely seen as a case motivated by anti-Semitism. Later, Frank’s death sentence was commuted by Georgia’s governor, which led a mob to storm the prison and lynch Frank.

Though their time at 70 Fifth Avenue would end in 1925, the NAACP’s momentum did not. Relocating to 69 Fifth Avenue for a time, then to various offices in Manhattan and Brooklyn, they would eventually move to Baltimore in the late 1980s. The organization, however, still maintains three regional offices scattered throughout the city. Since 1925, they have successfully fought for desegregation; created the Legal Defense fund; took part in organizing the March of Washington for Jobs and Freedom; supported same-sex marriage; created the Afro-Academic, Cultural, Technological and Scientific Olympics (ACT-SO) to recognize and award African-American youth who demonstrate accomplishment in academics, technology, and the arts; argued for greener and more environmentally sound policies; and continue to ensure the political, educational, social, and economic equality of rights of all persons, and to eliminate race-based discrimination.

For over a hundred years now, the NAACP has been an integral part of American history. Tooth and nail they have fought for equal rights and demanded justice where it seemed justice would never prevail. Their time in our neighborhood, while critical in the 1910s and 20s, is just as critical now as Village Preservation fights to landmark 70 Fifth Avenue. We provided extensive research and documentation on the significance of the building to the Landmarks Preservation Commission as part of our ongoing campaign to win landmark protections for this and other buildings south of Union Square. In January of 2021, the LPC voted unanimously to calendar, or begin the process of formally considering for landmark designation for 70 Fifth Avenue.

While we are heartened by this hard-fought and long-overdue victory, we must continue our pressure on the city and the Landmarks Preservation Commission to extend landmark protections even farther in this unprotected area south of Union Square, which contains many other great but unprotected landmarks of civil rights history. 70 Fifth Avenue is but one of nearly 200 vulnerable but historically significant buildings in this area from east of 3rd Avenue to west of 5th Avenue, 9th to 14th Streets for which we have proposed and are fighting for landmark designation via a historic district. After 2 1/2 years, this is the only additional building the City has agreed to move upon. We must note that a significant factor in this lack of progress is that unlike 70 Fifth Avenue, 90% of this vulnerable historic area lies in the district represented by City Councilmember Carlina Rivera, who has not supported the proposed landmark designation of this area, and who led the City Council’s approval of the nearby Tech Hub upzoning without the protections for the surrounding neighborhood she promised would be a condition of her support, thus vastly increasing pressure on this area.

We invite you to continue exploring the area South of Union Square using our South if Union Square map which features dozens of tours that highlight the extensive history of this area. Our Civil Rights and Social Justice map also features sites like 70 Fifth Avenue and Cooper Union’s Great Hall that have impacted not just African American rights, but LGBTQ, women’s rights, and more, and is a fantastic way to uncover the amazing impact our neighborhoods have had on American history.

One response to “The Birth of the NAACP, and Their Deep Roots in Greenwich Village”