Gen. George Washington Establishes HQ at Richmond Hill, April, 1776

Richmond Hill was a Colonial estate built on a 26-acre parcel of the “King’s Farm” in 1767 by Major Abraham Mortier, paymaster of the British army in the colony. Located southeast of the modern intersection of Varick and Charlton Streets, it served as George Washington’s headquarters in April-May and June-August of 1776, a period of critical importance during the early part of the Revolutionary War.

While many consider July 4, 1776 “America’s Birthday,” by then the Revolutionary War had already been going on for over a year, since the battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775. On June 19, 1775, the Continental Congress commissioned George Washington as Commander in Chief of the Continental Army. Throughout the fall and winter of 1775, Washington’s forces surrounded the British in Boston.

But even before the siege of Boston was resolved, Washinton knew New York would be a critical position. In January 1776, Washington dispatched General Charles Lee to survey the city and plan its defenses.

On March 17, 1776, the British evacuated Boston for Canada, where they would plan for the expected invasion of New York. Washington left Boston for New York on April 4th, 1776, staying in eight locations in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New York, before arriving in New York on April 13th, in advance of the expected attack.

From April 13th to 17th, Washington stayed at the William Smith House, located at Pearl Street, opposite Cedar Street.

On April 17, 1776, Washington moved his headquarters north to Richmond Hill. Richmond Hill was described as, “a mansion of massive architecture, with a lofty portico supported by Ionic columns, the front walls decorated with pilasters of the same order, and its whole appearance distinguished by a Palladian character of rich though sober ornament.“

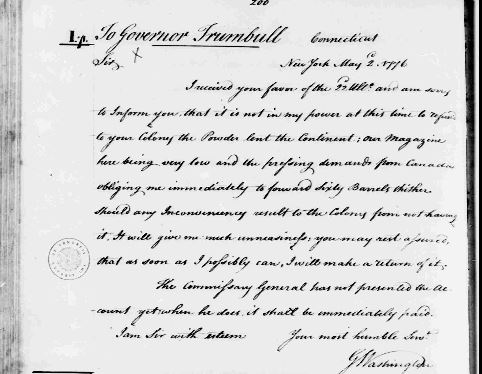

While at Richmond Hill, Washington wrote every day to various generals, lieutenants, and John Hancock, the President of the Continental Congress at the time. He was regularly in touch with the New York and New Jersey Committees on Safety, and on April 17th, he wrote a letter to the New York Committee of Safety regarding the city’s defenses. On April 24th he wrote to inquire about the raising of regiments and the state of their men and arms: From the accounts I have had, I have reason to fear there is a great deficiency in the latter; which at a Crisis, when nothing else seems left to decide the contest we are engaged in, is truly alarming & calls aloud on every power for their utmost exertions to procure ’em;

On April 29th, Washington issues a Proclamation on Intercourse with British Warships: Whereas an Intercourse and Correspondence with the Ships of War, and other Vessels belonging to, and in the Service of the King of Great Britain, is highly detrimental to the Rights and Liberties of the said Colonies.

On May 20th he wrote Benjamin Franklin with the bad news that the Siege of Quebec has been abandoned with some loss of cannon, a number of small arms, and provisions, but ended on a positive note: Things may assume a more promising appearance than the present is, and your difficulties in some degree be done away.

Washington left on May 21 for a short trip to New Jersey, returning to Richmond House on June 6. On June 28, he noted that his men had counted 130 British ships headed from Canada towards New York, carrying thousands of troops. On July 2, fifty British ships began landing troops on Staten Island.

Six days later, on July 9th, 1776 Washington’s army listened to a reading of the Declaration of Independence. Washington’s army was inexperienced and he believed that the Declaration would serve as a “fresh incentive” for his men to stay committed to fighting for the birth of a new nation.

Washington remained at Richmond Hill until August 27, when he moved his headquarters to Brooklyn for the Battle of Brooklyn, which was a disaster for the Continental Army and almost ended the war. Luckily, the army escaped back over the East River to Manhattan.

Washington led his Army through a calculated retreat up the east side of Manhattan, winning a minor victory at the Battle of Harlem Heights on September 16th. On October 21st he was forced to abandon Manhattan and make his headquarters in Yonkers when he realized the British were attempting to trap him on the island.

The campaign over New York that began in August 1776 continued to November 1776, when Washington fully retreated. The campaign featured the largest battles in the war to date, and the Americans suffered a series of defeats.

The war lasted seven more years before Washington victoriously returned to Manhattan on November 25, 1783. Follwing the war, Richmond Hill was purchased by Aaron Burr, John Jacob Astor, and later became a theater and opera house. It was Burr who mapped the property into lots of 25 by 100 feet on the three streets now known as Charlton, King, and Vandam Streets, much of which lies within the Charlton–King–Vandam Historic District.