Beverly Moss Spatt Oral History: the Landmarks Preservation Commission’s First Woman Chair

Village Preservation shares our oral history collection with the public, highlighting some of the people and stories that make Greenwich Village, the East Village, and NoHo such unique and vibrant neighborhoods. Each includes the experiences and insights of leaders or long-time participants in the arts, culture, preservation, business, or civic life.

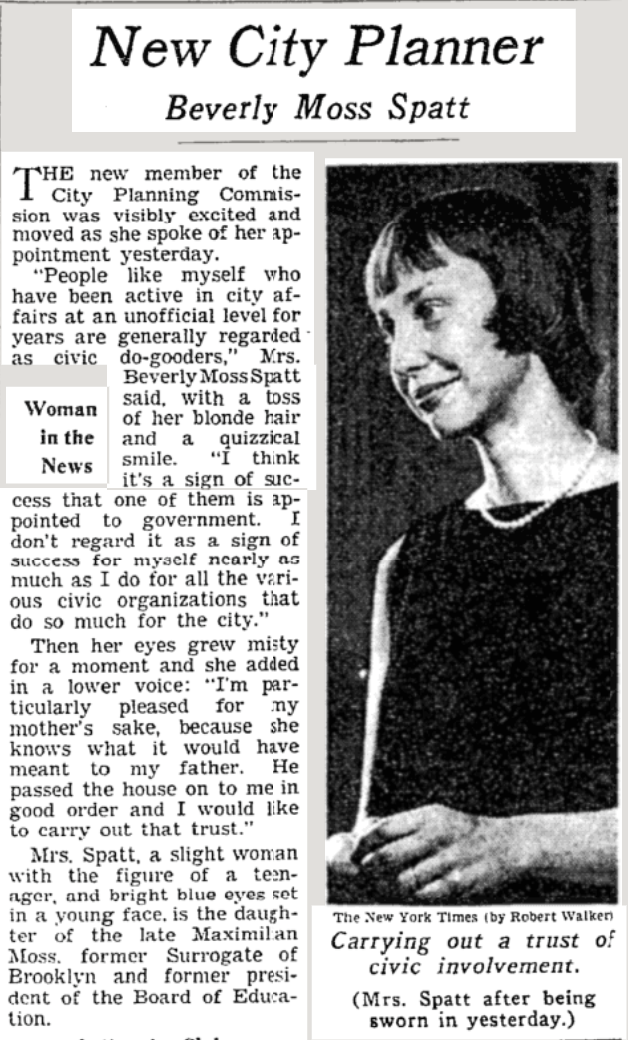

Beverly Moss Spatt has been a leading figure in city planning and preservation in New York City for over fifty years. In her Village Preservation oral history, Spatt discusses growing up in Brooklyn, how she helped form the first reform Democratic club in Brooklyn, how she earned her “maverick” reputation during her time on the City Planning Commission from 1966–1970, and serving on the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) from 1974-1982. At the LPC, Spatt was the first woman to hold the Chair position, which she did from 1974-1978. The 1973 Amendments to the New York City Landmarks Law went into effect the year of her appointment, allowing for the city’s first scenic and interior landmarks.

Beverly Adele Moss Spatt was born in Brooklyn, New York to Maximillian and Grace Moss. Her father was an attorney and the President of the New York City Board of Education, as well as an important philanthropic figure in Brooklyn and beyond. Her mother was a volunteer for the notable anthropologist Margaret Mead. Raised in the historic neighborhood of Brooklyn Heights, Spatt attended James Madison High School in Brooklyn, where she loved photography and rode horses in Prospect Park. Then, she went on to get her Bachelors’s degree at Pembroke College, the women’s college for Brown University (before the institution went co-ed), where she graduated cum laude in 1945. After graduation, Spatt met her husband, Samuel Spatt, who was a flight surgeon during World War II and later an internist physician. They had three children in quick succession: Robin, Jonathan, and David.

Spatt held several high-profile positions for the city of New York. She was a faithful member of the League of Women Voters, a chapter of which she helped to start in Brooklyn Heights. Spatt was active in civic life right out of college, and used her familiarity with city finances and government she’d gained in her time at the League, which proved to be an asset as she looked for work in public service, and as she pursued her graduate education in Urban Planning at New York University, earning her Ph.D. in 1976.

After a few smaller positions in the city, Moss joined the New York City Planning Commission in 1965, where she served from 1966–1970. During her time on the Planning Commission, she became famously known for her frequent dissents, which the New York Times often printed, dubbing her a “maverick” who sided with local communities. Among other issues, she dissented on a city-wide Master Plan, as well as on a zoning change affecting areas of the East Village, accusing the city of “selling zoning.” (Sound familiar?)

In 1974, Spatt was appointed to the Landmarks Preservation Commission as chair after proving her commitment to preservation issues and the public good. As Chair, Spatt’s goal was to be transparent, to serve the neighborhoods and communities. She strove to cultivate a Landmarks Commission comprised of non-partisan professionals who would not be influenced by political gain and the various persuasive tactics practiced by politicians. She also created an open-door policy—a first at the Landmarks Commission—that made her accessible to community members, students, and colleagues alike, and gave her the reputation as someone who was hands-on, and willing to listen to the public’s concerns. As she said in her oral history with us:

The powers that be didn’t like me, but most people are not powers that be. And that was helpful when I was on, became Chairman of Landmarks. They knew that I was there for them… When I dissented on the master plan, which caused me a lot of trouble, the regional planners’ association had a big meeting on the master plan, but of course, they didn’t invite me to speak…I had dissented, and my dissent was in the Times, and everything like that…

I didn’t want to become a dissenter, but, you know, I really believe that I was supposed to do what was good. The public will. The public good. And, you know, it’s always been real estate oriented, and real estate has always had power over––even now. I mean, this is not something new in preservation. And preservation wasn’t important then. But it was, it was very hard. (From Spatt’s Village Preservation Oral History.)

Spatt worked within communities to make preservation desirable and affordable to property owners, and educated the public about the benefits of owning a landmarked building and how to find public and private sources of funding to help owners with maintenance costs of historic buildings. She speaks about the importance of a having a nonpartisan commission and of working with other city agencies in order to be effective in the city. She speaks about the importance of working with communities when seeking landmarking and designation, and of keeping aware of the different ideas that various communities might have as regards to their built environment. As she also said:

You know, if you do good for the people, and you believe in something, people trust you.

Spatt’s tenure at the LPC also saw her involved in some iconic locations and battles in the city. Spatt notably persuaded then-mayor Robert F. Wagner to appeal the Grand Central demolition decision, given that the LPC had designated the building a landmark — this showed the true power of the LPC to stand up for buildings against developers who would see historic sites destroyed. Of this, Spatt said:

Grand Central––even though Jackie Onassis and the MAS [Municipal Art Society] gets all the credit, actually we at Landmarks, the city did not want to appeal the case. They didn’t want to because it’d cost a lot of money if we lost. So Dorothy Miner, who doesn’t get a lot of credit––Dorothy and I thought about it a lot, and I met with his deputy mayor, who was an old politician, who knew Beame, and I went down there, and I told him all the reasons why they have to appeal it. But we didn’t get credit for it. And he said to me, he said, “You and your assistant sure got balls.” Well, you know, as a feminist, I might object to that, but I didn’t object. I was happy that [laughing] they were going to appeal it. We don’t get credit for it.

Spatt was also involved in saving the Villard houses, designed by Stanford White, and gained private and public funding for over sixteen new programs including the Landmarks Scholar Program. She also oversaw the controversial designation of the Grace Church townhouses on Fourth Avenue (of which she said “The two sides were just up in arms”) and the new structure replacing the house destroyed by the Weatherman bomb explosion on West 11th Street.

During this time, Spatt also taught planning, preservation, public policy, housing, and community advocacy at the New School for Social Research (1967-1970) and Barnard College (1970-1983).

Following her service on the Landmarks Commission, Spatt stayed in Brooklyn and steped out of the public limelight. Spatt continued teaching, and also worked for Bishop Joseph Sullivan as a special assistant and speechwriter until 2013, and has kept involved in her communities.

After 61 years of marriage, Spatt’s husband passed away from heart failure. Moss remains in her family’s home in Brooklyn.

This is one of nearly 60 oral histories we’ve conducted which you can find in our collection, with prominent preservationists, activists, planners, artists, community, and business leaders. Some others you can find include Jane Jacobs, Rick Kelly, Mimi Sheraton, Ralph Lee, Fred Bass, Peter Ruta, Richard Meier, Merce Cunningham, Matt Umanov, David Amram, Verna Small, Marlis Mober, Jonas Mekas, Margot Gayle, Wolf Kahn, Lorcan Otway, Frances Goldin, Chino Garcia, Penny Arcade, and James Polshek, among many others. Explore them all HERE.

For more, check out…

- The full transcript of Spatt’s NYPAP Oral History with Spatt

- Brown University Library’s Page on the Beverly Moss Spratt papers here.

- Spatt’s oral history with Brown University, here.