#SouthOfUnionSquare, Mexican Muralists Remake American Art: David Alfaro Siqueiros and the Experimental Workshop

This installment of Village Preservation’s “South of Union Square, the Birthplace of American Modernism” series explores how the Mexican Muralists shaped some of the most influential American artists via their studios and workshops in the area South of Union Square.

After a decade of conflict, the Mexican Revolution came to an end on November 30, 1920 when Álvaro Obregón was sworn in as President. Obregón’s administration would go on to usher in what Austrian-American historian Frank Tannenbaum described as the “greatest Renaissance in the contemporary world.” One of the cornerstones of this cultural renaissance was the monumental public mural program created by the Obregón administration in 1922. These vibrant fresco works depicted Mexico’s pre-Hispanic traditions and redefined the relationship between the arts and the general public. Obregón’s alignment with the Partido Laborista Mexicano, or the Mexican Laborist Party, was apparent in the egalitarian depiction of Mexican workers, men and women, and national pride in the murals. American lefitist and labor publications such as The Nation, New Masses, and Creative Art, many of which did a great deal of work with artists, intellectuals, and writers in the area south of Union Square, wrote glowing reports about the politics and the murals, encouraging a flood of progressive Americans to visit Mexico. Between the end of Obregón’s term in 1924 and his assassination following reelection in 1928, political tension flared in Mexico and mural commissions nearly vanished. Between 1927 and 1940, Mexico’s leading muralists—José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, among others —came to the United States to execute lithographs and easel paintings, exhibit their art, and create large-scale murals. Many of the artists settled or took studios downtown, particularly around and south of Union Square area. This is one of the many reasons that Village Preservation is advocating for landmark designation for this endangered but historic neighborhood. From February 2020 – January 2021, the Whitney Museum of American Art, another iconic Greenwich Village institution, mounted a monumental survey of the Mexican Muralists’ important role in the development of American art; curated by Barbara Haskell, it was called Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925–1945.

One of the most consequential studios created during this time was David Alfaro Siqueiros’ 1936 Experimental Workshop located at 5 West 14th Street (no longer extant). The collective was a revolutionary influence in the artistic development of Jackson Pollock’s signature drip technique style as well as an inspiration to countless other artists. With two previous extended stays in the United States under his belt, Siqueiros arrived in New York City in February of 1936 and immediately leased the studio space at 5 West 14th Street that would become the Experimental Workshop. Shortly after arriving, Siqueiros gave an impassioned speech at the first American Artists Congress, on behalf of the Mexican Delegation about the Mexican Revolution. That speech posited that modern, innovative art could only result from social justice movements where artists and activists worked together in solidarity.

Shortly after his speech, Siqueiros published the Manifiesto de New York, which outlined the methodology governing the Experimental Workshop:

- Experimentation

- Research of technical aspects of art

- Studying the relationship between classical and modern techniques of art creation and the corresponding epochs

- Development of new art production techniques appropriate to modern times

- Producing public forms of works of art that are understandable and accessible to the general public

- Working and studying collectively in an environment without hierarchy

The first cohort of Experimental Workshop members were twenty-four-year-old Jackson Pollock, Pollock’s older brother Sande McCoy, George Cox, Louis Ferstadt, Axel Horn (previously Horr), Harold Lehman, and Clara Mahl (later Moore), along with artists from throughout Latin America, such as Luis Arenal, Roberto Berdecio, Jésus Bracho, Antonio Gutíerrez, and Antonio Pujol. Early works at the Workshop were for “the public use of art, big banners, floats, and big demonstration pieces and things of that nature for parades, gatherings, conventions, meetings. Not particularly for exhibit,” and were “ephemeral” in nature according to Siquerios’ studio assistant, Harold Lehman.

During the course of the Experimental Workshop, Siquerios developed a technique he called the “controlled accident” in which he would set up unconventional mark-making materials using industrial techniques and allow the materials to fall and react to one another where they may to compose the work. Siquerios shared the promise he saw in this technique in a letter to his friend María Asúnsolo:

“We have discovered something most wonderful…using the accident in painting, that is, using a special method of absorption of two or more colors on the surface produced snails and conches of forms and sizes most unimaginable with the most fantastic details possible. The discovery we made almost playing, but this “little game” would not have occurred to us if our theory did not include the initial investigation of all technical concerns, and if our theory was not based on the principle that without modern technique you cannot have modern art.”

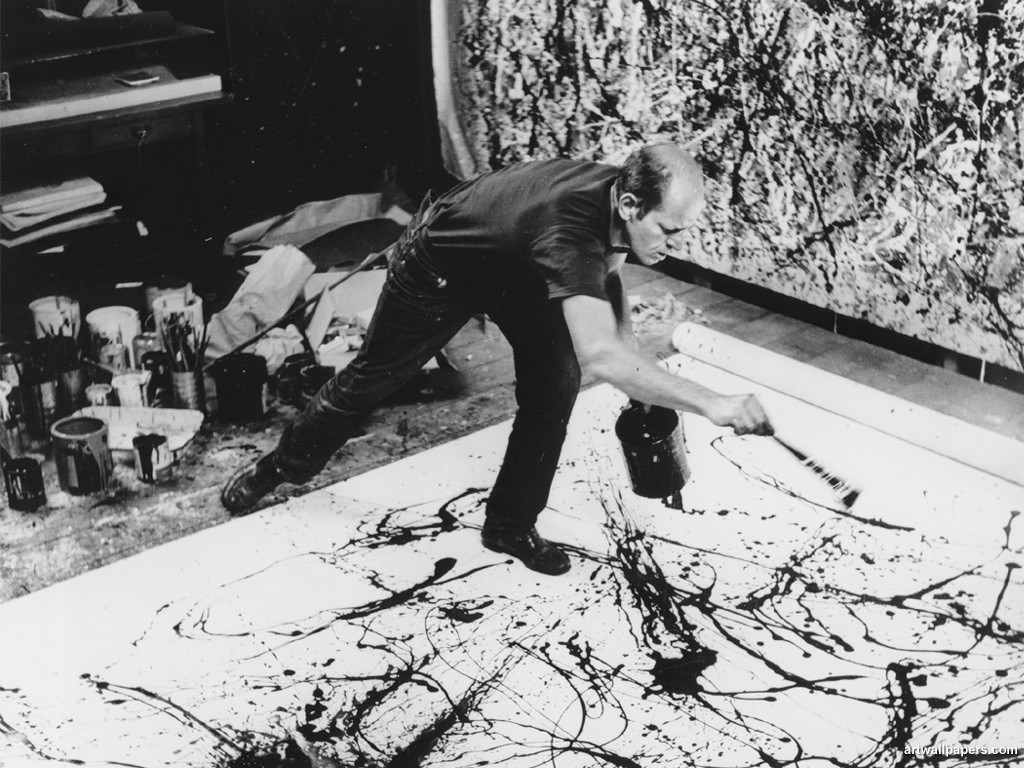

There is no question that the concept of the “controlled accident” had a seismic impact on Jackson Pollock. Image-making techniques ranged from dripping nitrocellulose from paint cans to build vivid fields of colorful streaks or punching holes in the lids of paint cans and spinning them on a Lazy Suzan atop a horizontal canvas.

Pollock’s works from this time period use the same visual language as the works from Siqueiros’ Experimental Workshop. The image-making techniques discovered in the course of the studio opened the door to his revolutionary drip painting technique. Siqueiros’ interest in automation, industrial technology, and unconventional materials set the stage for the American Abstract Expressionism movement. Pollock himself lived and in many ways began his artistic career South of Union Square, on East 10th Street.

Village Preservation has recently received a series of extraordinary letters from individuals across the world, expressing support for our campaign to landmark a historic district south of Union Square. While 5 West 14th Street is no longer extant, there are still dozens of buildings in this area related to the story of American art. You can help us landmark them by clicking here. To read more history of the buildings and area south of Union Square, and our preservation efforts in the area, click here.