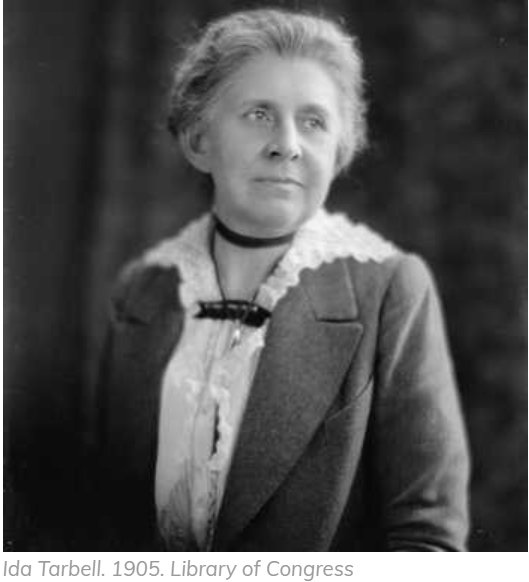

Ida Tarbell: An Icon of Investigative Journalism

Ida Tarbell was a woman far ahead of her time, as were many of those who found their way to Greenwich Village at the beginning of the 20th century. She was truly a trailblazer and remains an icon of reform. She famously took on big business and won in a way few others can claim to have. She pioneered the field of investigative journalism, and with her dogged demand for facts, she set the standard. We look to Ida Tarbell, and women like her, for much-needed inspiration in these challenging moments in our democracy.

Born in a log home on November 5, 1857, Ida Minerva Tarbell grew up in the oil region of northwestern Pennsylvania. Her father, Frank Tarbell, built wooden oil storage tanks and later became an oil producer and refiner. “Things were going well in father’s business,” she would write years later. “There was ease such as we had never known; luxuries we had never heard of. …Then suddenly [our] gay, prosperous town received a blow between the eyes.” The 1872 South Improvement scheme, a hidden agreement between the railroads and refiners led by John D. Rockefeller, hit the Pennsylvania oil region hard, and left independent producers and refiners out in the cold. The reverberations of this Trust would be felt in the industry for many years to come and would lay waste to the independent companies.

Ida Tarbell graduated Allegheny College as the sole woman in the class of 1880. Her inquisitive mind and her determination to have a career pushed her to become intensely invested in her writing and research projects. Her hope was to become a research scientist.

After graduation, Tarbell pursued the traditional role of becoming a teacher, one of the few career options open to women at the time. She intended to save money while teaching so that she could further her passion for scientific study. She reportedly hated teaching and soon thereafter abandoned it. Instead, she turned her pen to writing for a Methodist journal, The Chautauquan, serving a local but growing religious and educational movement. She discovered that she loved writing, and followed her passion to Paris, where she freelanced for several years.

She was subsequently hired by Sam McClure, editor of the eponymous McClure’s magazine, and returned to the United States. She was initially engaged to write biographies of Napoleon Bonaparte and Abraham Lincoln. But Tarbell’s greatest accomplishment lay ahead of her. Following the great success of those articles, McClure determined that she was ready for stronger stuff. He presciently decided that the next great topic would be the rise of monopolies and the consolidation of American industries in the hands of a few businessmen. He wanted Tarbell to write about one of them: John D. Rockefeller, whose Standard Oil Company controlled 75 percent of the market.

Readers were ultimately riveted by the 19-part series, written while she lived at 40 West 9th Street. Her story explained how the oil industry came to be dominated by one person, John D. Rockefeller, and how a monopoly could take control of public resources and marshall them for its own benefit. Her career took off from there, and Rockefeller’s reputation lay in shambles. Standard Oil was broken up, and Tarbell’s exposé forced the United States Courts to define and reinforce an area of previously vague law — which would become a powerful tool in later antitrust cases.

Tarbell later moved to The Hotel Griffou at 19 West 9th Street, where she lived from 1909 until 1919.

She is also closely associated with the 1848 Greek Revival townhouse on East Tenth Street that was owned and occupied beginning in 1923 by the Pen and Brush Club. Under the presidency of accomplished writer and suffragist Grace Seton, the Pen and Brush became an established legal corporation. Its founding mission was to offer opportunities for women in the arts at a time when women were excluded from membership in male-only arts club. The organization continued to flourish under the 30-year presidency of Ida Tarbell. Members have included Pulitzer Prize-winning authors Marianne Moore, Margaret Widdemer, and Pearl S. Buck, who also received the Nobel Prize in Literature; and renowned visual artists Isabel Whitney, Malvina Hoffman, Clara Sipprell, and Jessie Tarbox Beals.

Although Tarbell was not herself an advocate for women’s issues or women’s rights, as the most prominent woman in journalism and arguably the “Mother of Investigative Journalism,” as well as one of the most respected business historians of her generation, she nevertheless broke barriers for women by succeeding in the male-dominated worlds of journalism, business analysis, and world affairs.

As the author of “Ida Tarbell Portrait of A Muckraker,” I was so happy to see Lannyl Stephens’ piece about her and the photos of places she lived in the Village. I dearly wish plaques with her name could be placed at these addresses. I tried to explore this possibility at 40 West 9th Street long ago but I had no luck. If Village Preservation has any interest in pursuing this, or in any other project connected with her, I would be happy to help. Thank you!

What an important project to embark on – especially with so few women ever being recognized.