Catholic Churches: Anchor of New York’s 19th Century Irish Community

Irish Catholic immigrants to New York were one of the earliest and largest major immigrant groups to our city, outside of the Protestant immigrants from the United Kingdom who were much more readily accepted as “Americans.” They came here in ever-increasing numbers from the 18th century, seeking food security, jobs, religious and political freedom. Upon arrival, many met hostility emanating from anti-Irish and anti-Catholic sentiment. But they did not take these challenges lying down. Their fight for dignity, equality, and even survival can be seen in the stories of their churches, as can their remarkable success and eventual ascendance to power in New York City.

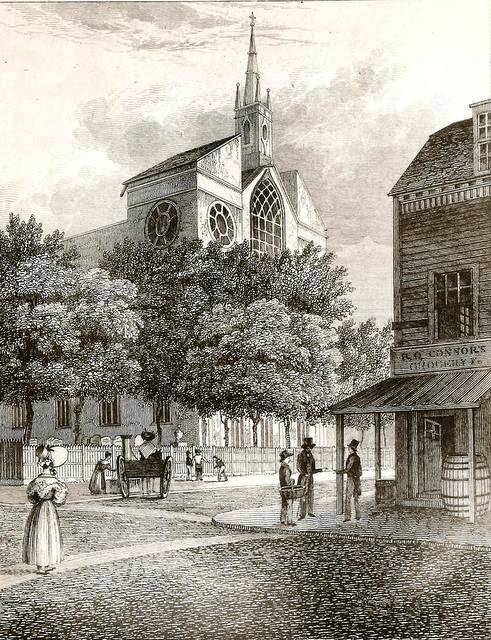

New York City didn’t have a Roman Catholic Church until 1785 when St. Peter’s Church was constructed on Barclay Street, placed beyond the city limits at the time at the urging of city leaders due to the prevalent anti-Catholic sentiments of many in New York (the present landmarked church there replaced the original in 1836.) And though they were a small minority of New Yorkers at the time, by 1808 the number of Catholics in New York had increased so much that Pope Pius VII established the Diocese of New York, appointing Jesuit Antony Kohlmann and several of his Jesuit brothers to lead it. Part of their task was to establish the Diocese’s first cathedral; Kohlmann chose the site of St. Paul’s Cemetery on the corner of Mott and Prince Streets. Joseph Mangin, a French-born architect and engineer, designed the church. St. Patrick’s Cathedral (now referred to as “Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral”) was completed in 1815 (it later burned down and was reconstructed on site), and John Connelly, an Irish Immigrant, became the city’s first Bishop.

In 1842, after two other bishops, who were unsatisfactory to the largely Irish Catholic population of the city, the Irish got someone who they felt represented them. Archbishop John Hughes, the son of poor Irish farmers from Country Tyrone, left behind poverty and British oppression, originally settling in Pennsylvania to study at St. Mary’s college. A popular apocryphal tale was Hughes would later gain the nickname of Dagger John for the shape of his dagger and the way he carried it by his chest. Actually, it meant that he was a man you did not cross lightly. In 1842, Hughes was appointed bishop of the growing archdiocese of New York City, which was coming under attack from growing anti-Catholic sentiment in the city, emblematic of the anti-immigrant, nativist “Know-Nothing” movement which was ascendant in the country at the time.

In the 1830s, growing anti-catholic sentiment began to explode. In 1831, St. Mary’s Church, the third Catholic Church built in NYC (a wooden structure), was burnt down. This violence prompted the diocese to raise the wall around the old St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Mott Street in 1834. The attacks continued, and Irish men were stationed at the walls to protect the Chruch, believed to have been placed there by John Hughes, serving as first as coadjutor and later administrator-Apostolic of New York before becoming Archbishop.

In 1844, tensions between the Irish Catholics and nativists began to come to a head in nearby Philadelphia. Simultaneously, James Harper, the head of the anti-immigrant party, was elected Mayor of New York. Galvanized by the believed support behind the anti-Irish stance, nativists torched two Catholic churches in Philadelphia, and a torch party gathered in City Hall Park who were preparing to march up the Bowery and burn St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Archbishop Hughes stationed gunmen along the church’s wall and sent a letter to Mayor Harper stating if a single Catholic church burned in New York, the state would become “a second Moscow,” referring to the scorched earth tactic from the Napoleonic invasion of Moscow.

The Irish continued to fight for their churches, including St. Joseph’s Church, constructed in 1829 in Greenwich Village, which is now the oldest intact Catholic Church in New York City. Archbishop Hughes continued establishing churches, such as St. Brigid’s or the “Famine Church” in the East Village, constructed in 1848, and colleges, including St. John’s College or Fordham University. Hughes then set his sights on establishing a grand Cathedral, soon dubbed Hughes’s Folly. The new St. Patrick’s Cathedral was something the people of New York thought would never get built, but James Renwick Jr. designed the Cathedral, and Archbishop Hughes laid the cornerstone of the new cathedral’s foundation in 1858. The Cathedral was constructed on donations from wealthy and poor Catholic New Yorkers alike. By the Cathedral’s completion, Tammany Hall was gaining power, and the Irish were taking a more and more dominate role in New York City politics, moving from outsiders to insiders. And of course, St. Patrick’s Cathedral became a draw for the wealthy citizens of New York, receiving massive donations for continued improvements over its lifetime.

The siting, burning, defense, and expansion of Irish Catholic churches (and eventually grand cathedrals) in and around our neighborhoods shows the evolution of the place of Irish immigrants in our city, from an underclass often treated with hostility or even violence, to attaining the height of economic and political power. We have previously highlighted some of the most influential Irish Political leaders and philanthropists in New York City, many of whom were rooted in our neighborhoods. Their story continues to shape our city today.

“Hughes would later gain the nickname of Dagger John for the shape of his dagger and the way he carried it by his chest.”

I believe this claim is mistaken.

Catholic bishops in the 1800s traditionally signed their name beginning with a “t” to symbolize the holy cross, then their name and title followed.

Those who received correspondence from Archbishop John Hughes and were unaware of this Catholic clerical tradition misinterpreted the cross that preceded his name as a dagger; hence, t Archbishop John Hughes became known as Dagger John.

See, https://aoh.com/2021/03/16/archbishop-dagger-john-hughes/

Need the Irish parish which was close to 30th Street in Manhattan. Have heard of JTB, but could have been another. My Grandpa and Grandma were married in April 1920 and my Grandpa lived near 30th Street and he worked at the USPO. Any help is welcome… Rf