The Gilded Village: Where Two Thirds of the Population Lived

Our Gilded Age blog posts have previously looked into some of the major stores and influential people of the era in our neighborhoods South of Union Square. This period, from the end of the Civil War until around 1900, is renowned for its excess, luxury, and wealth enjoyed across American cities. Rapid economic growth bolstered by industrialization and urbanization raised workers’ wages and prompted immigration from countries not experiencing the same prosperity as the United States. The ever-expanding railroad was shrinking the country, making it easier for those settled in rural areas to move to cities in search of work. This era, which saw such dramatic economic growth, also saw a huge increase in income inequality. By the end of the Gilded Age, over 80,000 tenements had been built in New York City, even as the mansions on Fifth Avenue were being constructed, high-society parties were being thrown, and elegant and indulgent shopping emporia were being built. But more than two-thirds of the city’s population was living in cramped, unsanitary, and poorly regulated conditions in buildings known as tenements.

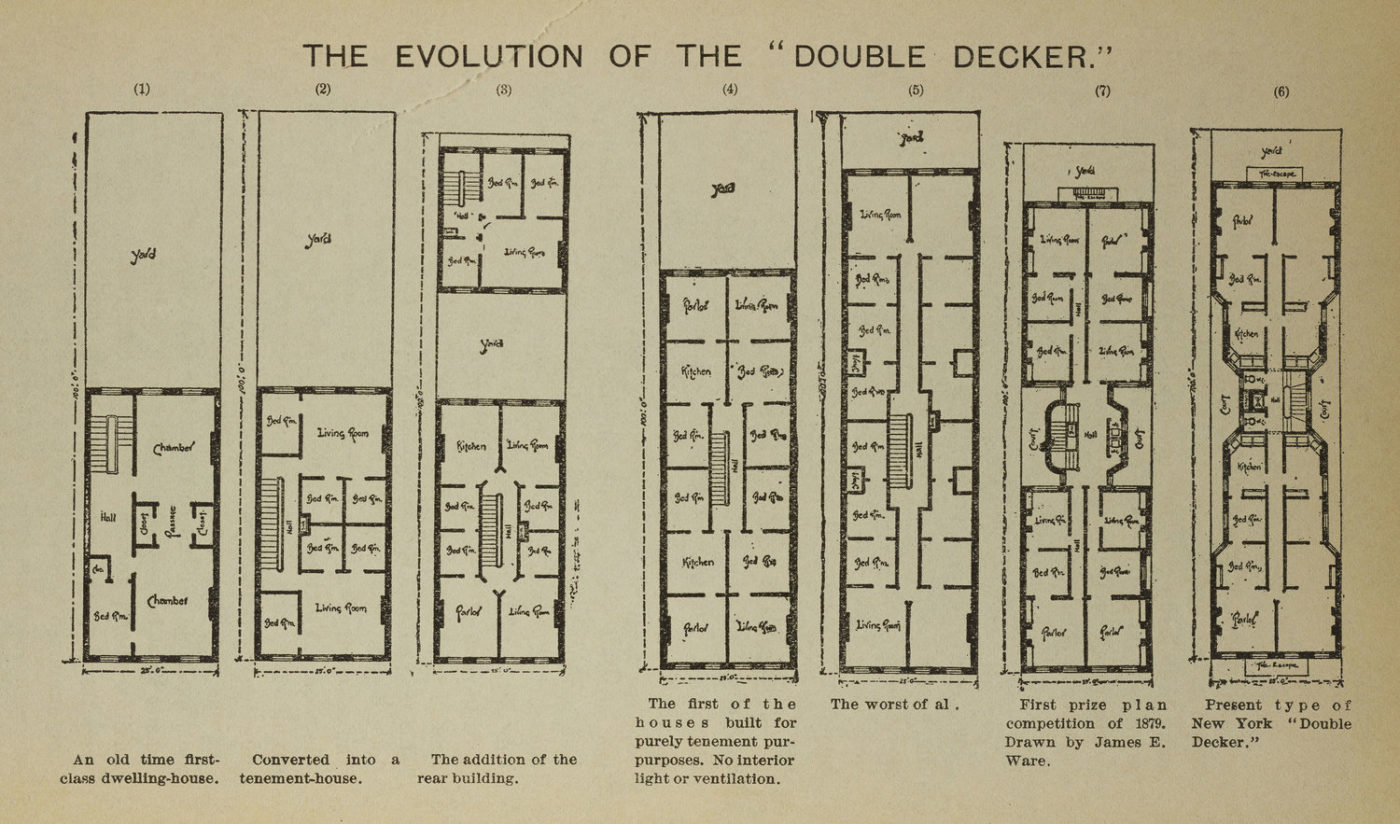

New York City tenements are typically divided into three categories: “pre-law,” “old-law,” and “new-law.” The first pre-law tenements were built in the 1830s; some were purpose-built as multi-family housing, while others were former single-family homes converted (often via expansion) to accommodate many families. Famine in Ireland and revolution in Germany — both in the 1840s — were major catalysts for massive immigration to New York City and the construction of tenements (read more about tenements in the East Village here and the South Village here).

Prior to 1879, there was very little regulation regarding tenement design or construction. However, in 1879 the Tenement House Act of 1879 or “Old Law” was passed. Tenements that pre-date the law’s requirements are often referred to as “Pre-Law” tenements, or, more awkwardly, “Pre-Old Law” tenements.

The 1879 law created the iconic “dumbbell” tenement that often comes to mind when thinking of New York City tenements (the “dumbbell” refers not to any over-simplicity or lack of thoughtfulness to the design, but to the small air shafts it required in the middle of the building which gave it the shape of a dumbbell when viewed from above, as per the below right). While this law mandated a minimum of light and air in tenement house rooms (of questionable value; the narrow shafts helped spread as much disease, fire, and refuse as they did light or air), it didn’t place any regulations on the existing tenements; it’s requirements to provide access to light and air in each room through a street-facing window, a rear yard-facing window, or an air shaft only applied to new construction.

Following the 1879 tenement law, even greater waves of immigration to the United States and specifically New York began — no longer just from Great Britain, Ireland, Germany, and France as in earlier waves, but from all across Southern, Eastern, and Central Europe as well, among other locations (there was also the migration of African Americans from the South, though in small numbers compared to the “Great Migration” of the early 20th century). This prompted developers to begin constructing rows of tenements in neighborhoods like Greenwich Village and the East Village, as well as the nearby Lower East Side.

Many were overcrowded with few if any sanitary facilities or baths, and ten to twenty or more people living in three-room apartments. Diseases such as cholera, typhus, and tuberculosis began to spread. The wealthy in the city were not unaware of the living conditions, in large part thanks to Jacob Riis’ How the Other Half Lives. But it wasn’t until the 1890s that the public on a large scale began to acknowledge the severe deficiencies in the conditions in many of these tenements, especially those which dated to before 1901.

During the winter of 1893, the East Side Relief Work Committee (ESRWC) was formed to “whitewash” the tenements. The ESRWC hired unemployed men and women to sweep the streets, nurse the sick, clean the sewers and trash, scrub the floors and walls, and whitewash the apartments, alleyways, cellars, and airshafts. When cleaning the tenements, the ESRWC found so much trash that some piles reached nearly 3 feet high. The call for help and donations was put out in the NYTimes in February of 1894, describing it as a “benefit that will be felt by the rich and poor alike.” This work was aided by rich society men and women in New York and even Tammany Hall. It led to several other committees forming that had little impact on the conditions until 1898 when the Tenement House Committee was formed.

The Tenement House Committee investigated the conditions in tenements and sought to educate the public on the conditions those living there were facing. This committee fought hard for changes in building codes. In 1899, the city proposed a new building code, and a state commission drafted the new Tenement House Act. The act was passed on April 12, 1901. It outlawed the dumbbell shape and set a minimum lot size requirement for the building. It also required running water, lighting, ventilation, and indoor bathrooms. This act became a model for housing regulation across the United States.

While Riis’ How the Other Half Lives was very enlightening, the title was perhaps a bit misleading; How The Majority of the City Lives might have in many ways been more accurate. The men and women, mostly immigrants, who worked as vendors, laborers, and tailors in sweatshops and came to the United States in search of religious or political freedom, economic stability, or food security often faced incredibly challenging living conditions. The city failed them for a long time, and though the Tenement House Act of 1901 was a giant leap forward that finally addressed many of these shortcomings, the next phase of efforts to address inadequate housing in our city took the form of “slum clearance” — a practice which leveled and destroyed existing communities, which almost always consisted of immigrants, the poor, and/or people of color, and rarely provided them with a worthy substitute in its place.

Fascinating, and one would like to read more about life in tenements. Also, photos of tenements that still stand (outside and interiors) would help to illustrate the three ‘laws’ by example. At some point well into the 20th century toilets were used by many tenants in back courtyards. Bathtubs were of course in the kitchen. These buildings still exist.