Seeing Wright in the Village

Frank Lloyd Wright’s (June 8, 1867 – April 9, 1959) contributions to American architecture are wide and varied; his low slung Prairie style homes that irrevocably changed American residential design and his smooth seashell spiral of the Guggenheim Museum overlooking Central Park are among the most significant architectural works of the 20th century. While neither would likely feel quite “at home” on the streets of our neighborhoods, Wright’s profound influence can still be felt here — through an influential unrealized project, and the works of his proteges.

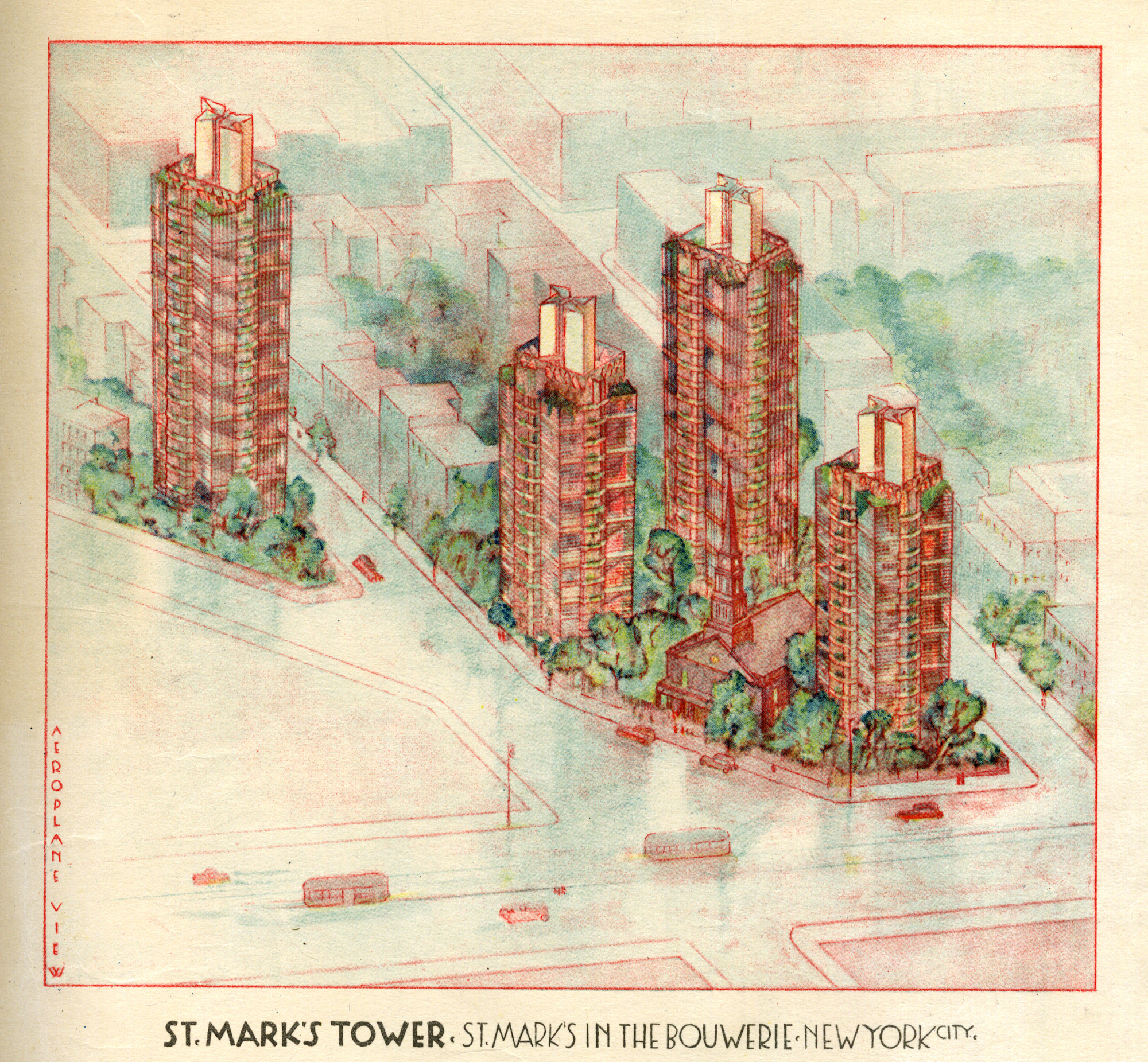

In 1927, Reverend William Norman Guthrie, a radical clergyman, author, visionary, and Rector of St. Marks-in-the-Bouwerie Church from 1911 to 1937 commissioned his friend and long time collaborator Frank Lloyd Wright to design several modern apartment towers in the East Village at 11th Street and 2nd Avenue just behind the historic church (next to the church’s rectory, which also happens to be the current home of Village Preservation).

Rooted in Wright’s Usonian vision, the design of the apartment towers featured an organic “tap-root” structural system with a central load-bearing core extending to the subterranean bedrock. This freed the interior from intrusive load-bearing walls which allowed for custom partitioning and a curtain wall to grace the exterior façade. (St. Mark’s would also have been the earliest modern tower in New York, predating the UN building and Lever House by more than 20 years.)

The project, which would have been one Wright’s few works in New York City, is also one of the architect’s very few and earliest skyscraper designs. The Great Depression and the reluctance of many to live in such a modern environment killed the project. However, the major features of the design were included in his 1956 H.C. Price Company Tower in Bartlesvile, Oklahoma.

But Wright’s legacy in our neighborhood extends well beyond the theoretical or unrealized. Edgar Tafel (March 12, 1912 – January 18, 2011) was a long-time Greenwich Village resident and one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s earliest and most successful proteges. Tafel was one of the original group of Taliesin Fellows in Spring Green, Wisconsin. He studied and worked with Wright for 9 years. During a time when “glass box” architecture was cutting edge and considered the height of modernism, Tafel was not afraid to reference surrounding historical forms in a distinctly modern way. One of the best examples of this is his 1958 Church House of First Presbyterian Church, located on the northwest corner of the church’s property on West 12th Street just west of Fifth Avenue. In his design for the Church House, Tafel was tasked with creating a modern gathering space that was in conversation with the historic 1844-1846 sanctuary designed by Joseph C. Wells. Tafel was resoundingly successful in this task. The 1969 Greenwich Village Historic District designation report glowingly describes the building:

“Here, with its fifty-foot frontage on Twelfth Street, Edgar Tafel, the architect, has managed, through the use of subdued colors, harmonizing materials, and good design, to achieve a building that complements its older neighbors and enhances the neighborhood. Dark brown Roman brick walls are carried up as piers between the windows and are further enhanced by dark green terra cotta mullion strips which lend a vertical accent. Horizontal terra cotta balconies at second and third-floor levels display a continuous, traditional Gothic quatrefoil pattern. The parapet, of similar design and material, crowns the whole composition successfully. Although the large windows are of plate glass, the detail of the terra cotta, the brickwork, and the balconies tend to keep in scale with the adjoining residential buildings and thus keep the larger building in character with them. The Church House is an example of good design, used intelligently, to bring a much needed contemporary building into harmony with a neighborhood.”

Another example involves Albert Ledner (January 28, 1924 – November 14, 2017). Ledner was born in the Bronx and moved with his family to New Orleans, Louisiana at just 9 months old. After high school, Ledner enrolled in the Tulane School of Architecture, but by his sophomore year the United States was fully involved in World War II and Ledner was recruited to the Camouflage Corps and later the Army Air Corps. During this time, Ledner was based in Tuscon, Arizona, just a short drive from Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin West, and he began to work with the famed architect. After the war and graduating from architecture school in 1948, Ledner began a fellowship at Taliesin in Spring Green, Wisconsin. Ledner learned from Wright a sensitive way to connect a building with its environment. This is evident in Ledner’s best-known New York building, the National Maritime Union of America at 20-40 Seventh Avenue. While a distinctly different architectural style than the surrounding neighborhood, the scale and proportions of the building are in conversation with the built environment. The 1969 Greenwich Village Historic District designation report describes the building:

“The large five-story building of the National Maritime Union of America is a striking contemporary structure. Erected in 1962-63 from plans by Arthur A. Schiller and Albert Ledner, it serves both as National Headquarters and as its Port of New York office. The main portion of this building fronting on the Avenue is a glistening white, built above two curving glass block walls. It has two overhangs at the top floors which are dramatized by their scalloped edge profiles. These overhangs produce an interesting play of light and shade. The rectangularized pattern of the jointing of the stone veneer lends a new dimension to the building, making us double aware of the various wall planes. Bubble-shaped covers of Plexiglas serve to display ship models around the base, outside the glass block walls. Behind this main mass a six-story section rises up, extending through from street to street. On West Twelfth Street it runs from Nos. 211 to 219.”

So while you may only be able to imagine Wright’s work when walking around our neighborhoods, you can actually see that of two of his most prominent acolyte, set within the context of the Greenwich Village Historic District.