The Death and Life of Louis Sullivan

On April 14, 1924, the architect Louis Sullivan, the “father of modernism,” key figure of the Chicago and the Prairie Schools of Architecture, progenitor of the skyscraper and coiner of the phrase “form follows function,” died.

None of these descriptors would lead one to believe that Sullivan would have any relationship to Greenwich Village, much less a beloved one. But much as his sad and tragic death gave little indication of the stature and influence of his life and career, his pioneering work giving visual identity to the skyscraper and stripping architecture down to its most essential elements nevertheless found a distinct and remarkable home in Greenwich Village.

When Sullivan died, he was a penniless alcoholic, his burial and funeral paid for by Frank Lloyd Wright. Sullivan was a mentor to Wright, his student; Wright so revered Sullivan, he called him “Lieber Meister,” German for “dear master.”

Sullivan’s route to such an ignominious ending was a tortuous one. Born September 3, 1856, his career as an architect was on a meteoric rise in the late 19th century, when with partner Dankmar Adler he pioneered the visual expression of the new built form, the skyscraper.

For this exciting technological marvel of the new world, Sullivan chose to eschew old world forms and thinking. The author of the manifesto “The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered,” Sullivan urged architects not to mimic traditional building forms when designing skyscrapers, but to let their tallness define them, to look to nature for inspiration in forms, to draw the eye upward, and to inspire. Rather than the neo-Renaissance or Gothic or Second Empire style skyscrapers which were being built in New York City, Sullivan’s “Chicago Style” buildings were ahistoric. They looked like nothing which came before them, and took their visual cues from the steel structure underneath, accentuated by florid, naturalistic ornament.

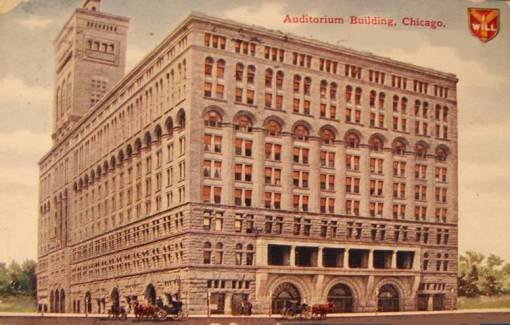

This took the form of many stunning skyscrapers in his hometown of Chicago, including the Auditorium Building, the Carson Pirie Scott Department Store, and the Chicago Stock Exchange, as well as the Guaranty Building in Buffalo, and the Wainwright Building in St. Louis.

Sullivan’s sole work in New York comes from this first period of his career, when he was still designing skyscrapers. The Bayard-Condict Building at 65 Bleecker Street, completed in 1899 at the head of Crosby Street, is a stunning surprise. Unlike most of his other skyscrapers, the Bayard-Condict Building is wedged between other buildings on three sides, and thus has only one façade with which to express Sullivan’s revolutionary design ideas.

But what a façade it is. Its thirteen stories rise to one of the most lushly decorated cornices anywhere, capped by a sextet of angels which are a final burst of glory before the building meets the sky. The façade is literally drenched in terra cotta ornament one could only describe as “Sullivan-esque,” with urns and arches and lacey foliate forms (many of these decorative elements had actually been removed from the first and second floors during a 1960’s renovation to “modernize” the storefronts; they were meticulously restored in 2002, winning a GVSHP “Village Award“.)

Sullivan’s groundbreaking design, while beloved now, had little impact upon design in New York at the time. The location of this, one his last skyscrapers, in a then-gritty, industrial area, was indicative of the relatively recent but dramatic downturn in Sullivan’s fortunes. One of the most celebrated American architects of the 1880’s and early 1890’s, Sullivan was winning commissions throughout America and influencing design. He put the United States on the architecture map in a way that it had not been before, turning the young country for the first time away from mimicking European models and showcasing a building form and a style which was uniquely its own.

In fact, Sullivan may have been at the apex of both his career and his skills in 1893 when he was commissioned to design the Transportation Building at the World Columbia Exposition in Chicago. Possibly one of the most stunning buildings ever created, this temporary World’s Fair structure took Sullivan’s aesthetic to a whole new level, imbuing his innovative proto-modern, organic designs with a visual embodiment of the then-new electricity which powered the fair.

Sullivan’s stunning design stood out not just because of its electrifying style, but because nearly every other structure at the fair hued to a Beaux Arts aesthetic referred to as “The White City.” This imperial vision turned its back on Sullivan’s distinctly modern and American style. Where Sullivan sought to express and impress based upon the realities of his time and place, the Beaux Arts White City of the fair sought to paint America as a natural continuation of the empires of Europe, an emerging power which looked toward the imperial designs of Rome or Paris rather than the American Plains or the steel skeleton of a skyscraper for inspiration.

In the proverbial blink of an eye, in spite of designing what may have been the most stunning building of his career or his age, Sullivan and his aesthetic almost immediately fell from fashion.

Commissions dried up even in Sullivan’s hometown of Chicago. But at least into the 1890’s the great innovator continued to design skyscrapers and other large buildings, though a shocking number of these were demolished in later years.

But by the turn of the 20th century, the Beaux Arts movement in America, which had also come to be known as the “City Beautiful” movement, was in complete ascent. Following the Spanish-American War and the United State’s acquisition of its own oversees empire, Sullivan’s innovative style lost more and more adherents in favor of this new imperial aesthetic. Through the first two decades of the 20th century, Louis Sullivan, once the brightest light in American architecture and builder of Chicago’s Auditorium Building, the “tallest, largest, and heaviest building of the time,” was relegated almost exclusively to designing banks in small Midwestern cities and towns.

While the Commissions may have been modest and the locations obscure, Sullivan’s designs were anything but. Buildings like the National Farmer’s Bank in Owatonna, Minnesota (1908) and the Merchants’ National Bank in Grinnell, Iowa (1914) were stunningly lyrical monuments which belied their modest scale. As revelatory and sublime as these buildings were, unfortunately they could not stop Sullivan’s continuing fall from fashion and favor. By the late 1910’s Sullivan’s commissions grew smaller and smaller, including the Purdue State Bank in West Lafayette, Indiana (1914), the People’s Federal Savings and Loan Association in Sidney, Ohio (1918), and the Farmers and Merchants Bank in Columbus, Wisconsin (1919).

Often referred to as Sullivan’s “jewel boxes,” these tiny structures were no less rich in texture, ornament, or innovation than his larger projects. Ironically, unlike many of his larger and once-celebrated commissions in big cities which met the wrecking ball, almost all of Sullivan’s bank buildings from this very difficult period of his life and career still stand. This is likely owing at least in part to the fact that they were located in less economically successful, off-the-beaten path locales which, unlike the major cities in which many of Sullivan’s grander commissions were located, were less interested in the shifting winds of architectural fashion and therefore less anxious to redevelop and replace any structure no longer deemed de rigeuer.

Unfortunately by the 1920’s even these obscure commissions dried up for Sullivan. His final work, the Krause Music Store, was an incredibly modest two-story residence above a music shop located in a quiet and relatively removed residential neighborhood in Chicago. Adding insult to injury, the commission by store owner William Krause did not even go to Sullivan, but to his former student William Presto, who in turn asked his one-time mentor to design of the facade. Sullivan was broke, in poor health, and living in a rented room at the time. Perhaps knowing that this would be his swan song, Sullivan seemed to pour every ounce of his talent and ingenuity into this humble work.

The façade is a final burst of glory embodying Sullivan’s genius with ornament; an unimaginably rich composition in terra cotta on an otherwise humdrum commercial strip. The deeply inset entryway for the store and the medallion above the second floor reflect Sullivan’s brilliant juxtaposition of geometric and curvilinear forms of nature.

Not even this final burst of brilliance could save Sullivan, however. While the store opened in 1922, Sullivan did not receive another commission, and died two years later at the age of 67. He was crushed not only by debt, alcoholism, and a cruel lack of recognition of his contributions to architecture. According to biographer Robert Twombley, though he never publicly identified as such, Sullivan likely also faced the challenges of being gay at a time when such an identity or orientation faced harsh social and legal stigma and sanction.

The fate of the Krause Music Store, like the Bayard-Condict Building on Bleecker Street, in some ways reflected the continuing descent and gradual rehabilitation of its visionary designer’s reputation, detailed here:

The store opened to sell pianos and sheet music, and was a pioneering retailer for the introduction of the radio. Tragically, with the onset of the Great Depression, William Krause committed suicide in the family’s apartment on the second floor. His widow rented and eventually sold the building to a funeral parlor. During the next 60 years, the building functioned as a funeral home, undergoing much neglect and alteration. The terra cotta façade was acid washed, which ultimately damaged and lightened its color. The basement was converted into a workspace for embalming the dead.

On September 20, 1977, the City of Chicago recognized the historic significance of the building and designated the façade as a Chicago Landmark. Thirteen years later, Scott Elliott opened Klemscott Galleries and restored the front of the building to its original intent. By the turn of the new century, a gift shop called The Museum of Decorative Arts occupied the space. In May 2005, the building was purchased by Pooja and Peter Vukosavich, who painstakingly restored the historic Sullivan façade and completed a modern renovation of the main floor for their company offices, Studio V Design – a marketing communications and design agency. The building is now a serene and elegant space with a meditative “zen” garden, fostering a dynamic environment for creative design.

After a long period of foresakenness and neglect, the Krause Music Store now finally shines again, its breathtaking façade has been restored and granted the recognition it deserves. So too, fortunately, has Sullivan’s place in history.

Sullivan was hugely influenced by his brief employment in the Philadelphia office of architectural visionary Frank Furness. There he learned the Furness Office method of developing plans from funtional need rather than formulae or archetype; massing and embellishment to emphasize heierarchy of use; steel as both exposed structure and ornament; the embracing of industrial materials and techniques; ornament divorced from historical president; and a language for abstracting natural forms into original decorative designs – all manifested throughout his brilliant career.

Sullivan’s earliest independent works were clear paraphrases of Furness projects – as Wright’s earliest independent works were paraphrases of Sullivan. In the 1950s at the absolute nadir of Furness’ reputation as an architect, Wright journeyed to Philadelphia to see the buildings that had so inspired and influenced his master, pronouncing the then reviled buildings as “the works of a true artist”.

Great article. Thank you for showing me the music building which I mus5 now see in person. This great architect gave us so mischievous beauty and so much to discover again.

Great Article! Thank you!

He is my hero and the reason I wanted to go to Columbia for historic preservation. Sadly, in the years since I returned to Chicago three of his few remaining buildings have caught fire. One, however is being converted into the National Museum of Gospel Music – the former Pilgrim Baptist Church (originally built as a synagogue).

https://nationalmuseumofgospelmusic.org/

DID LOUIS SULLIVAN HAVE ANY CHILDREN

He did not.

Wonderful article. Thank you.

I went to Grinnell on a tour of America, looked over at his jewel box bank and was hit by the thunderbolt.