Electric Lady Studios: Jimi Hendrix, And So Much More

Jimi Hendrix would have turned 75 this week. In his brief 27 years and even briefer musical career, Hendrix left an indelible mark upon guitar playing and rock music, permanently transforming both art forms. But perhaps in some ways his most lasting impact came from a project completed just three weeks before his death–the opening of Electric Lady Studios at 52 West 8th Street in Greenwich Village. On August 26th, 1970, the studio opened, the only recording artist-owned studio at the time. It provided Hendrix with affordable studio space that would also meet his personal technical and aesthetic specifications.

Kicked off by an opening party near summer’s end, Electric Lady Studios was the location of Hendrix’s last-ever studio recording–an instrumental known as “Slow Blues”–before his untimely passing on September 18, 1970. Fortunately, this was only the beginning of the studio’s incredible run recording some of the greatest rock, hip hop, and pop albums of the last nearly half-century and only the latest incarnation of one of the Village’s most unusual and storied structures.

The Clash, Lou Reed, Kiss, Led Zeppelin, Blondie, Run DMC, The Roots, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, Nas, Kanye West, Madonna, Beyonce, Stevie Wonder, Billy Idol, U2, Adele, Frank Ocean and Daft Punk, among many others, have recorded at Electric Lady Studios. By many accounts, Patti Smith ushered in the punk era by making her first recordings there. David Bowie was propelled to superstardom in the United States as a result of his collaborations with John Lennon there. The Rolling Stones’ comeback album “Some Girls” and AC/DC’s “Back in Black,” the best selling hard rock album of all time, were both recorded there as well.

As fascinating as its history as a recording studio, Electric Lady Studios and the building which houses it has an interesting and unusual history prior to its current incarnation. Before being turned into a recording studio, 52 West 8th Street housed the popular music venue the “Generation Club,” where Hendrix, Janis Joplin, B.B. King, Chuck Berry, and Sly and the Family Stone, among many other musicians of the day, performed.

Prior to that, the basement of the building contained “The Village Barn,” a country-themed nightclub and dining hall, from 1930 to 1967. Believe it or not, The Village Barn even spawned an eponymous country music program on NBC, the first country music program on American network television. The show ran from 1948 to 1950, and featured weekly performances from the likes of “Pappy Howard and His Tumbleweed Gang,” “Harry Ranch and His Kernels of Korn,” and even Oklahoma Governor Roy J. Turner, who performed his single “My Memory Trail.”

In one of the more stunning cultural juxtapositions, Abstract Expressionist painter Hans Hoffmann lectured upstairs in a studio in the building from 1938 through the 1950’s, contemporaneously with the Village Barn’s residence and TV run.

Painting and music were not the only art forms which called this building home. Until 1992, it also housed the beloved 8th Street Playhouse, which pioneered the midnight movie and hosted the Rocky Horror Picture Show and its floorshow every Friday and Saturday night for eleven years starting in the late 1970s.

And the building was an architectural landmark as well as a cultural one. It was first built in 1929 as the Film Guild Cinema, one of the earliest examples of modernist or constructivist architecture in New York, designed by architectural theoretician and De Stijl member Frederick Keisler. He intended the theater to be “the first 100% cinema,” with a modernist design intended to fully immerse the viewer in the film.

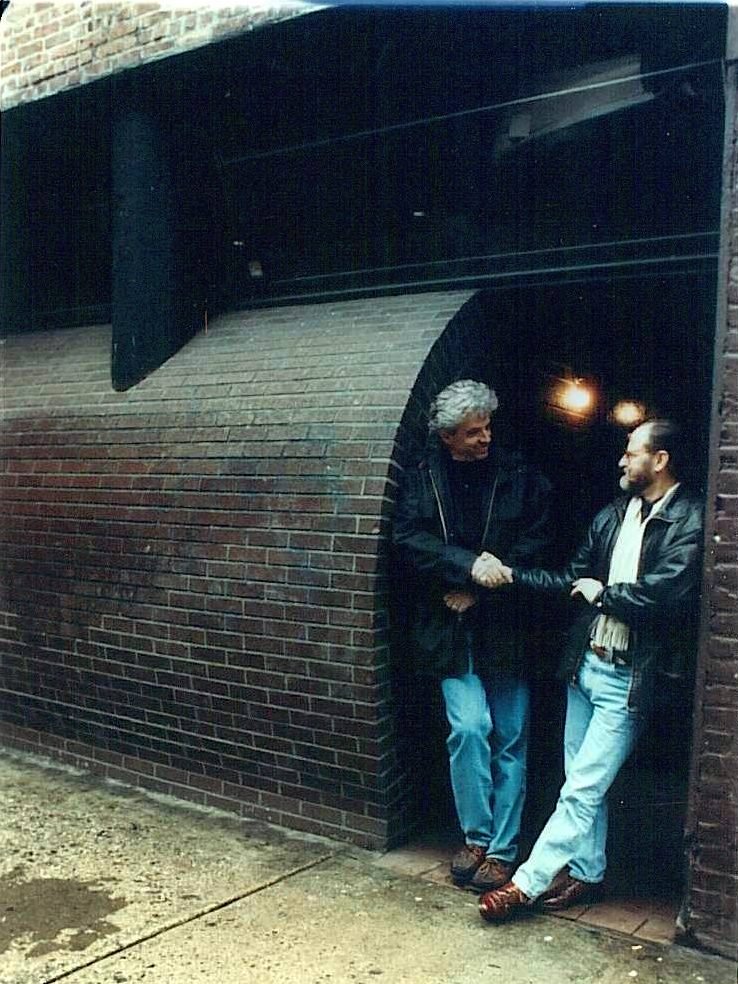

Sadly, by the end of World War II, the distinctive modernist and constructivist ornament and marquee on the theater had been stripped away. The building would have to wait another 25 years, for the arrival of Hendrix and company for an avant-garde design to again take hold here. For Electric Lady Studios, Hendrix, John Storyk, an architect and acoustician, and Eddie Kramer, Hendrix’s producer and engineer, dreamed up rounded windows, a concave brick exterior, and a 100-foot-long floor-to-ceiling mural on the interior by artist Lance Jost, which gave the studios an unmistakable connection to Hendrix which survived long after.

Much as with the Film Guild Cinema, however, the cutting edge look would not last. About 20 ago the building was given a mundane makeover, eliminating the undulating brick façade. But artistry and innovation remain alive and well inside. Just a few of the landmark recordings made there: The Clash’s “Combat Rock,” Blondie’s “East to the Beat,” Stevie Wonder’s “Fulfillingness’ First Finale,” Prince’s “Graffiti Bridge,” Led Zeppelin’s “Houses of the Holy,” Billy Idol’s “Rebel Yell,” Run DMC’s “Tougher Than Leather,” and Alice Cooper’s “Welcome to My Nightmare.”

A version of this article originally appeared in 6sqft.