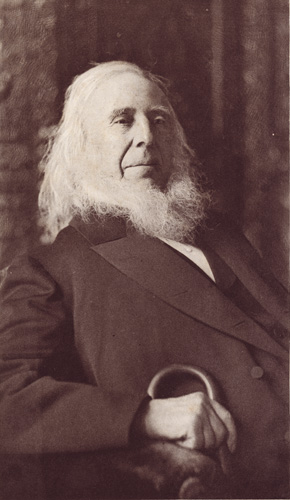

Saluting Peter Cooper

Born on February 12, 1791, Peter Cooper left his mark on the world as a pioneering industrialist and inventor, and his mark on the Village as a great philanthropist. Cooper began his career as a coachmaker’s apprentice, although he had only one year of formal schooling. He also worked as a cabinet maker, hatmaker, brewer, and grocer. From these humble beginnings he became one of the great American businessmen, innovators, educators, and humanitarians of the 19th century, leaving an enduring legacy which lives on to this day.

In 1824, Cooper purchased a glue factory on Sunfish Pond in Kips Bay in Manhattan, successfully developing new ways to produce glues, cements, gelatin, and other products. In 1828 he used profits from the factory to purchase 3,000 acres in Maryland, which he believed would skyrocket in value due to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. As he drained the swamps and flattened the hills, he discovered iron ore on his property and founded the Canton Iron Works in Baltimore. When the railroad foundered, Cooper developed the Tom Thumb steam locomotive in 1830, a groundbreaking advance as the first American-built steam locomotive. The engine drove the success of the B&O, allowing the railroad to purchase Cooper’s iron, which, along with his investments in real estate and insurance, earned him a fortune.

Cooper lived frugally and invested much of his fortune in philanthropy. In 1851, Cooper was one of the founders of Children’s Village. It was originally founded as an orphanage called the “New York Juvenile Asylum” and today serves over 10,000 children each year at ten New York area locations.

According to Edwin Burrows & Mike Wallace in Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, Cooper served as head of the Public School Society, which was a private organization that ran New York City’s free schools using city money. From this, Cooper developed the idea of having a free institute in New York that would offer practical education in the mechanical arts and science and in 1853 ground was broke for the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art.

Cooper’s social views were far ahead of his time. In a time of extreme class, race, and other divisions, classes at Cooper Union were non-sectarian and egalitarian (although 95% of the students were male). The Great Hall, also known as the Foundation Building, was designated a landmark in 1966. According to the designation report, The main building of Cooper Union is one of those proud buildings on the American Scene which may rightly take its place with the pioneer buildings of all lands. It was here that innovations were made both in the physical structure of the building and in the use for which it was designed – all of them brainchildren of the great philanthropist Peter Cooper.

The Cooper Union library remained open until 10 pm so working people could access it after work. Prior to the Civil War, Cooper was active in the anti-slavery movement. In 1860, Abraham Lincoln, who was not yet the Republican candidate for president, made an impassioned speech in the Great Hall that he and many historians believe propelled him to the presidency. In what is considered one of Lincoln’s most important (and longest) speeches, he claimed that the Founding Fathers would not want slavery tp expand into the western territories.

Following the Civil War, Cooper was active in the Indian reform movement. He privately funded the United States Indian Commission, which was dedicated to the protection of Native Americans and the elimination of warfare in the western territories. He personally sponsored Indian delegations to Washington, D.C. and New York City to meet with Indian rights advocates and to address the public on Indian policy.

At 85 years, Cooper ran for president in the 1876 presidential election for the Greenback Party. He remains the oldest person ever nominated to run for president. Also way ahead of his time on banking, Cooper was a passionate critic of the gold standard and the debt-based monetary system of bank currency. He advocated a credit-based, government-issued currency and in 1883 his addresses, letters, and articles on public affairs were compiled into a book, Ideas for a Science of Good Government.

Cooper’s son, Edward Cooper, would serve as Mayor of New York City from 1879-1880 and promoted reform of the city’s sanitation service and tenement laws. In addition, Cooper’s son in law Abram S. Hewitt would also serve as Mayor, from 1878-88 (prior to consolidation in 1898 mayors were elected to two-year terms; post-consolidation, terms were four years).

Cooper passed away in 1883 and was interred at Green-Wood Cemetery.