Beyond the Village and Back: Congregation Shearith Israel

In our series Beyond the Village and Back, we take a look at some great landmarks throughout New York City outside of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and NoHo, celebrate their special histories, and reveal their (sometimes hidden) connections to the Village.

Congregation Shearith Israel, now located at 2 West 70th Street, takes pride in being the very first Jewish congregation in North America, where something like half the world’s Jewish population now lives. It was founded in 1654 by 23 Jews of Spanish and Portuguese descent who had been living in a Dutch colony in Brazil. When the colony changed hands and the Portuguese took over, the Jewish community fled to avoid the imposition of Inquisition policies, which had previously pushed their families out of Portugal and Spain in the late 15th and early 16th centuries.

About Congregation Shearith Israel

Shearith Israel was the only Jewish Congregation in New York City from 1654 until 1825. As the only synagogue, it was Shearith Israel to which Jewish residents of New York turned for education, worship, charity, and community.

At the time of its founding, the Congregation wasn’t even legally allowed to practice their religion publicly, but this didn’t stop them from renting space on Beaver Street at the southern tip of Manhattan. However, it did take until 1730 for the community to build a synagogue of its own, and since that time it has resided in four locations.

The First Mill Street Synagogue, which they moved into in 1730 and expanded in 1818 (on today’s South William Street) was consecrated in 1730. It was the very first structure in North America designed and built as a synagogue.

Next, they moved to 60 Crosby Street, in today’s SoHo. That synagogue was completed in 1834.

From there they moved to 5 West 19th Street, just west of Fifth Avenue, in today’s Flatiron District. That synagogue was completed in 1860.

Finally, they moved to the synagogue’s current landmarked location at 2 West 70th Street on the Upper West Side, which was built in 1897.

Today’s grand Seventieth Street Synagogue of the Congregation Shearith Israel was designed by Arnold Brunner with interior and windows by Louis Comfort Tiffany.

According to the synagogue, their current location had previously housed a duck farm. To create the building, the Congregation selected Brunner, an American Jewish architect with a distinguished career. Brunner designed this beautiful neo-classical style building, called by the Congregation “a reflection and reaffirmation of its commitment to tradition.” Louis Comfort Tiffany designed the interior, its color scheme, and most notably the gorgeous stained glass windows.

So Shearith Israel never had a synagogue in Greenwich Village or the East Village, leapfrogging over these neighborhoods in their 19th century uptown migration. So what’s their connection to the Village? One could argue that they owe their existence to one East Villager, and they left a pretty memorable legacy in Greenwich Village.

Rebuffed by Peter Stuyvesant

Much of Congregation Shearith Israel’s early fate was determined by one very powerful resident of the East Village — Peter Stuyvesant. Stuyvesant’s home, farm, and chapel were all located in today’s East Village, and many vestiges of Stuyvesant’s wealth, power, and visions for the neighborhood are still visible today We’ve written extensively about Stuyvesant, whose authority also made him an arbiter of rights in the colony. He was strongly opposed to religious pluralism, and as such made life quite hard for the Jewish refugee founders Congregation Shearith Israel. For context, Stuyvesant also sowed conflict with Lutherans, Roman Catholics, and Quakers as they sought to practice their faiths publicly and privately.

When the Jewish refugees arrived in New Amsterdam after fleeing Brazil, Stuyvesant seized their possessions and ordered them sold at auction, and jailed two members of the group. Stuyvesant wrote to the Dutch West India Company in Amsterdam, asking permission to expel the Jews. The Jewish community in Holland petitioned the Dutch West India Company, and the company ultimately denied Stuyvesant’s request, thus giving the Jews of Shearith Israel (and by extension of New Amsterdam) a permanency and stability which they previously did not have, though they were not given permission to worship in a public synagogue for some time.

The West 11th Street Shearith Israel Cemetery

Soon after the 23 Spanish and Portuguese Jews of Sherith Israel arrived in New Amsterdam, they began to make arrangements for the creation of a cemetery — the very first Jewish burial ground in North America. In 1656 the New Amsterdam authorities granted the Shearith Israel Congregation “a little hook of land situated outside of this city for a burial place.” Its exact location is unknown, and it has long since been destroyed. The Congregation’s second cemetery, which is today known as the “First Cemetery” because it is the oldest surviving one, was purchased in 1683. That “First Cemetery” was located at 55-57 St. James Place near Chatham Square in Lower Manhattan, and many of the bodies from the actual first cemetery were moved there.

When the “First” cemetery began to fill to capacity, a “Second” cemetery needed to be established, and they purchased a much larger plot of land in then-rural Greenwich Village. The West Eleventh Street cemetery, or “Second Cemetery” of Congregation Shearith Israel, was consecrated on February 27, 1805. Some of the bodies from the First cemetery were moved there, including some which date to the earliest Jewish settlers of New York. At first, this was only a satellite cemetery. But in 1823, city public health ordinances banned burial in the congregation’s first cemetery at Chatham Square, making the West 11th Street Cemetery the congregation’s only burial ground. Among those buried here are the Revolutionary War veteran Ephraim Hart, and the noted painter Joshua A. Canter.

The Second Cemetery on 11th Street operated until 1829; during that time the establishment of the Manhattan street grid cut 11th Street through the cemetery, dislodging most of it (many of those bodies were moved to the “Third” cemetery, which still exists on West 21st Street). The small triangular section of the much larger, original cemetery that remains today on West 11th Street is still owned and maintained by the Shearith Israel congregation, now located on the Upper West Side.

Greenwich Village’s Oldest and Narrowest Houses

Two of the most iconic landmarks of Greenwich Village — its oldest house and its narrowest house — owe their existence to members of Congregation Shearith Israel and the descendants of those 23 original Jewish settlers of New York.

In 1799, when Greenwich Village was still a place of farms and rolling hills, Joshua Isaacs began building his wooden home on the corner of Bedford and Commerce Streets, now numbered as 77 Bedford Street. Isaacs finished the house a year later, making it the oldest surviving building in Greenwich Village, and one of its few surviving wooden houses (though a brick front was added years later). Almost immediately, Isaacs was forced to declare bankruptcy. His son-in-law, Harmon Hendricks, who was married to his daughter Sarah, bailed him out by buying the property in 1801. Both were members of Shearith Israel (which was still at the time the only synagogue in New York), and descendants of the original Sephardic Jewish settlers of New York. The house has come to be known as the Hendricks-Isaac House.

Some sources, including The Book of Jewish Lists, say that Hendricks, an iron and metal titan, was the first millionaire in the country. It bragged: “The first millionaire in America…was Harmon Hendricks, a Sephardic Jew who founded America’s first copper rolling mill in the late 1700s.” The New York Times also profiled Hendricks, calling him a “pioneer.” Along with his brother Solomon, their office on South William Street was prosperous, and among other clients, they were agents for the well-known Bostonian Paul Revere, which would put them deep in the realm of revolutionary supporters. That and the War of 1812 generated a great deal of work for Hendricks, and his father-in-law Jacob Isaacs, who partnered with him in his work. In addition to 77 Bedford Street, Hendricks purchased the block of Greenwich Avenue between Bank and 12th Street, among other properties both north and south of the Village.

When Hendricks died in 1838, he was buried in the Third Shearith Israel Spanish Portuguese Synagogue Cemetery on 21st Street in Chelsea. Hendricks left his estate to his six children. His daughter Hettie, who was married to Aaron L. Gomez, another Sephardic Jew who was also a member of the Shearith Israel Congregation, got the Bedford Street house. They left the house to their son Horatio. Dr. Horatio Gomez was a 19th-century doctor and descendant of Abraham Haim de Ludena, one of the original Jewish refugees who fled Brazil in 1654, when the Congregation was founded. Dr. Gomez was also a philanthropist and a prominent member of Shearith Israel. He was a longtime member of the Board, and an active participant in the Congregation’s charitable and educational societies. When the synagogue at 2 West 70th Street was consecrated in 1897, Dr. Gomez had the honor of being the first to open the Aron Kodesh, the ark which holds the holy Torah scrolls. This same honor was bestowed upon his great-great-grandfather Luis Moses Gomez in 1730, at the consecration of their Mill Street building.

The New York Tribune set an atmospheric scene in its writeup of the dedication:

Slowly and with dignity a gray-haired man, wrapping his talith about his shoulders (the talith is a fringed shawl of white silk, bordered with blue, which ministers and members of any Orthodox Jewish congregation must wear when performing religious rites), came forward and opened the doors. He was Dr. Horatio Gomez, a lineal descendant of Louis Gomez, who was one of the first Jews to arrive in New York, some time before 1680… In the hallway was a forest of white satin rolls, the “scrolls of the Law,” held in the arms of distinguished men. Behind them were the five Spanish-Portuguese ministers of America.

The Gomez family also built 75 1/2 Bedford Street between 1854 and 1862, now known as the narrowest houses in New York City. One of its first occupants was German-born shoemaker Jacob Bloom and his family. Some of its later occupants were a bit more famous than Mr. Bloom, including the poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, Cary Grant, John Barrymore, and children’s author Ann McGovern, who wrote Mr. Skinny’s Skinny House with illustrations showing 75 1/2 Bedford Street. Another children’s author who lived here was William Steig, who wrote Shrek and Sylvester and the Magic Pebble, as well as being a cartoonist for The New Yorker. Steig’s sister-in-law, anthropologist Margaret Mead, also lived there. Dr. Gomez died in 1909 and the properties on Bedford stayed in the Horatio-Gomez family until 1923. After they were sold, they almost immediately acquired by a group of artists, including Millay, who turned them into theaters and housing for artists, including today’s Cherry Lane Theatre.

Greenwich Village, and New York’s, Landmark Legacy

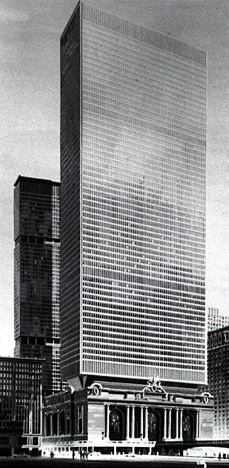

In a delightful twist of fate, it was the great-great-grandson of Harmon Hendricks (of Congregation Shearith Israel and of 77 Bedford Street fame), Harmon Hendricks Goldstone, who became the first full-time Chair of the newly-established New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1968, and who presided over the landmark designation of the Greenwich Village Historic District, which included 75 1/2 and 77 Bedford Streets and about 2,200 other historic properties in Greenwich Village. Goldstone oversaw many of the great early landmark designations in New York City, including that of the St. Mark’s Historic District (which includes the final resting place of Peter Stuyvesant, the man who tried to expel Goldstone’s forebearers from New Amsterdam) and the SoHo Cast Iron Historic District. Perhaps his most lasting legacy, however, was his rejection of plans to build a skyscraper above the landmarked Grand Central Terminal, which resulted in the successful Supreme Court decision ultimately affirming the legal basis for landmark designation, which remains with us to this day protecting our city’s architectural and historic legacy.

Learn more about Congregation Shearith Israel here, and discover more about a long history of a place on 70th Street with deep connections to Greenwich Village and the East Village.

My grandfather, Louis Napoleon Levy, was Parnas (President) of Shearith Israel for 32 years. He was born at 117 Bank Street. He died in 1921 at the age of 66.

Unbeknownst to me then, my husband and I purchased 72 Bank Street in 1964, at auction from the real “Auntie Mame”, Marion Tanner, where I still reside.

I am a 10th generation New Yorker. I derive from the 23 original Sephardic Jews who landed here in 1654. From its beginning, my family has been interwoven with the development of New York as a great port City. Harmon Hendricks and Harmon Hendricks Goldstone are in my family tree.

The article you wrote interests me and my family greatly. Thank you for writing it.

Sincerely, Nancy B. Hoffman