Beyond the Village and Back: Bowne House in Flushing, Queens — Birthplace of Religious Freedom in America

In our series Beyond the Village and Back, we take a look at some great landmarks throughout New York City outside of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and NoHo, celebrate their special histories, and reveal their (sometimes hidden) connections to the Village.

One of New York’s most historic but least known landmarks is the Bowne House, built ca. 1661 at 37-01 Bowne Street in Flushing, Queens. The two-and-a-half story wood house is the oldest building in the Borough of Queens and one of the oldest in New York City. And while we tend to think of our neighborhoods as defined by an iconoclastic struggle against authority and for greater personal freedoms, the Bowne House speaks to an oft-forgotten period of our history when absolute power and authority emanated from here, and was used to deny exactly the pluralism and liberties our neighborhoods came to be known for celebrating and embracing.

Bowne House was built by John Bowne (March 9, 1627-1695), a Quaker and the family patriarch, whose defense of religious freedom led to the creation of the principles later codified in the Bill of Rights, the first ten amendments of the United States Constitution. After emigrating from England to Boston in 1649, he eventually settled in Flushing, then under Dutch rule. Over the course of 300 years, the family, and the home itself, left an indelible mark on American culture, participating in events of both regional and national significance.

Robert Bowne (b. 1744), the great-grandson of John Bowne, was both an early and prominent abolitionist active in the anti-slavery movement. In 1785, he joined with Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, Thomas Eddy, and George Clinton (who was married to Hannah Bowne Franklin) to form the Manumission Society of New York, which in turn founded the African Free School in 1787. The Manumission Society’s work included protesting the widespread practice of kidnapping black New Yorkers (both slave and free), only to sell them elsewhere, and providing legal assistance to both free and enslaved blacks who were being abused. The Society additionally lobbied for passage of the 1799 law in New York which granted gradual manumission of slaves.

Initially, children of New York slaves born after July 4, 1799, were freed but indentured until they were young adults. In 1817, a new law was passed which freed New York slaves born after 1799, but not until 1827. Nevertheless, fugitive slaves from the South and free blacks in the North still faced significant risks and danger of captivity. The Bowne House Historical Society, which maintains the home itself and an extensive archive, recently discovered correspondence that directly links Robert Bowne’s niece, Mary Bowne Parsons, her sons, and the home, to the Underground Railroad. A letter dated September 28, 1850, soon after the passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, requested assistance in the escape of a “colored man.” Robert and William Parsons are asked if they can keep the man perfectly unobserved in his neighborhood as Williamsburg was considered too close to the City for safety. The letter concludes by stating “[t]his is a strong case and great care and caution is involved”. The obituary of another son of Mary Bowne Parsons, Samuel Bowne Parsons, Sr., who ran the Parsons’ nursery on land near the House with his brother Robert, noted his boast that he had “assisted more slaves to freedom than any other man in Queens County.”

With all of this incredibly rich history, perhaps the most significant thing connected to the Bowne House, and the basis for its original place in American history, took place almost 200 years before John Bowne’s descendants were risking their lives to protect African Americans, and is inextricably linked with the history of our neighborhoods. In fact, Bowne’s foundational role establishing the American system of religious freedom would not have been possible were it not for one of the East Village’s earliest — and most notorious — residents.

Soon after he arrived in Flushing, Bowne was butting heads with one of the most powerful men in the New World: Director-General of New Netherland Peter Stuyvesant. The St. Mark’s Historic District in the East Village is built entirely upon land which was part of the farm Stuyvesant purchased in 1651. Stuyvesant Street, at the heart of the district, was part of a grid of streets eventually laid out upon lots on that farm, which followed true east-west, rather than the somewhat eschewed orientation of Manhattan Island which today’s Manhattan street grid follows. Stuyvesant Street is the only remaining street from that pre-Manhattan grid, and originally divided two farms, or “Bouweries” (the Dutch term)

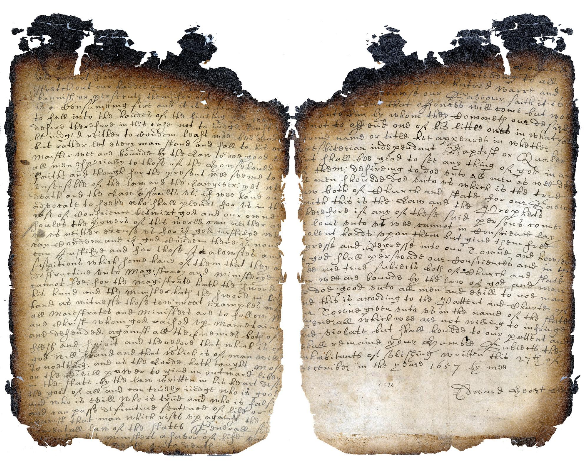

St. Mark’s Church is built on the site of Peter Stuyvesant’s former private church, thus making it the oldest site of continuous religious worship in New York City. On December 27, 1657, some thirty residents of the Flushing settlement, then called Vlissingen, signed a petition known as the Flushing Remonstrance (read the full text), requesting an exemption to Stuyvesant’s 1656 ban on Quaker worship (and his insistence that everyone practice under the Dutch Reformed Church), which included an Ordinance declaring that any person entertaining a Quaker Meeting House for a single night was to be fined and that vessels bringing any Quaker into the province would be confiscated. Sentiment grew quickly in Flushing to oppose this infringement upon the right to enjoy the liberty of conscience as provided in the town charter of 1645. The Remonstrance is now considered an important precursor to the United States Constitution’s provision on freedom of religion in the Bill of Rights.

Stuyvesant ignored the petition, punishing a few of the signers, and his ban on religious diversity remained in effect. It was John Bowne who forced the issue by allowing Quakers to gather in his home for worship. John’s wife Hannah had joined the Society of Friends (as they were known) and became a minister. Family lore tells that Bowne was converted by Hannah, with evidence he was a Quaker by 1661 when they attended out-of-state Friends meetings together.

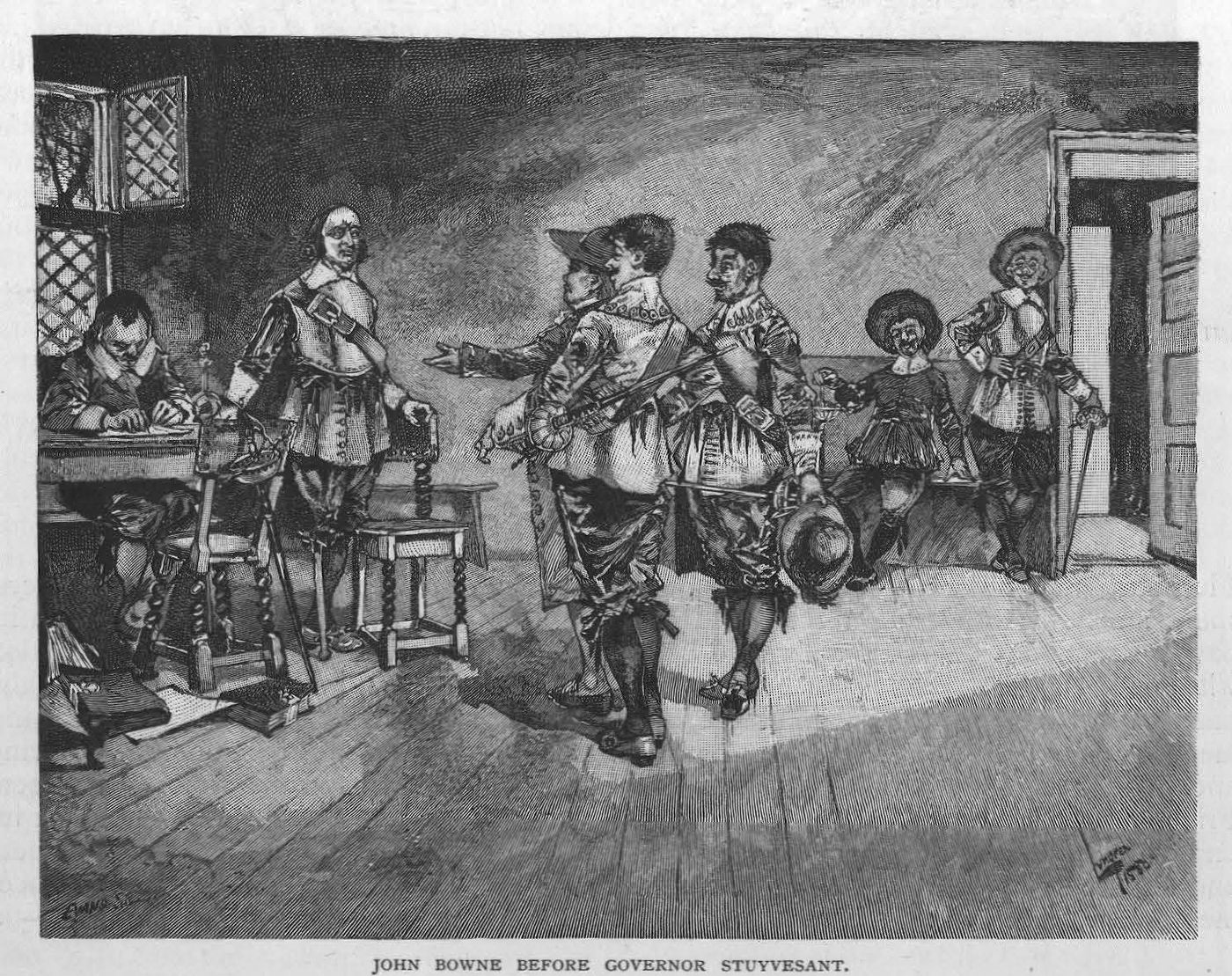

In 1662, Stuyvesant sent his sheriff to arrest Bowne and take him to jail in New Amsterdam. Bowne remained there for several months. When it became clear that Bowne would not recant, repent, or pay the fine demanded, Stuyvesant had him deported. Bowne made his way to England, and then to Holland, where, citing the language of the Flushing Charter, he testified at his trial before the Dutch West India Company, which owned the colony of New Amsterdam and, thus, was responsible for Stuyvesant’s actions. The Company agreed and ordered Stuyvesant to permit freedom of religion in the colony.

This freedom evolved over 100 years later into the guarantees in the First Amendment to the Constitution. Also guaranteed there are the rights of assembly and freedom of speech — all principles advanced by John Bowne in 1662 with the simple act of welcoming Quakers into his home.

Bowne returned home in 1664. He continued to farm, acquired extensive land holdings in Queens and in Pennsylvania, and had a successful business selling books and engaging in other commercial ventures. After Hannah’s death, he remarried twice and had a total of sixteen children, of whom eight survived. He helped to acquire the land for the Flushing Quaker Meeting House and burial ground on Northern Boulevard. The Meeting House still stands and is one of the oldest Meetings in America. The site is now a National Historic Landmark.

Both John Bowne and Peter Stuyvesant were buried underneath their respective houses of worship, Bowne at the Meeting Burial Ground and Stuyvesant underneath what is now St. Mark’s church.

Fascinating History. A man who stood by his principles. I believe I am one of many descendants. My GreaT Grandmother was Sophia Bowne who’s father was John Edgar Bowne. . Just trying to trace the lineage

Amazing story of sticking through your perinciples and bending down to anyone’s will even going to a forigen place agasint all odds for you.Very interesting!!Thank you for the simplicity.