#SouthOfUnionSquare Tour — Libraries and The Formation of the NYPL

In 1754, there was no library in New York. Can you believe it? Today we are taking a wonderful journey through our neighborhoods to trace the beginnings of the New York Public Library which came to light through several important institutions, philanthropists, and buildings. With the help of our new Virtual Village map and its library tour, we can explore the history South of Union Square and find out how the New York Public Library came to be.

Six individuals would band together in 1754 to create a library which “would be very useful as well as ornamental to the City.” The premise was a simple one: anyone could join, and joining gave one the ability to check out a broad range of books, or enjoy books on-site. Books included fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and reference titles.

The New York Society Library originally occupied one room in the old City Hall at 26 Wall Street, which eventually came to be known as Federal Hall after George Washington’s inauguration there in 1789. In 1795, with a catalog of 5,000 books, the NY Society Library finally moved out of Federal Hall to 33 Nassau Street, where it hosted the likes of Washington Irving and James Fenimore Cooper. In 1840 the Society moved again, this time to Leonard Street and Broadway, where Henry David Thoreau and John James Audubon were members. In that space, they combined with the New York Athenaeum, a literary and scientific club of the day. As the library’s collection increased to thirty-five thousand volumes by 1856, it became necessary to build a much larger building.

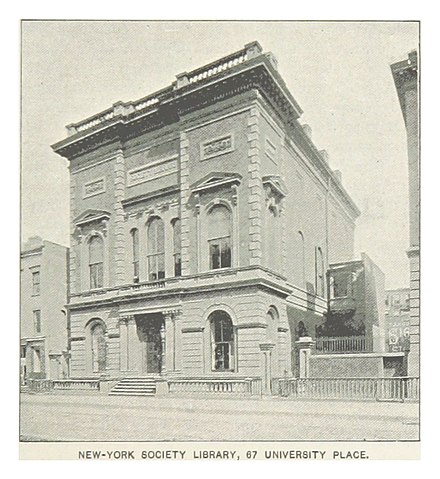

And so in 1856, the New York Library Society moved to Greenwich Village. It built and took up residence in a beautiful building located at 67 University Place between 12th and 13th Streets. The street numbers were changed in 1895, and 67 University Place became 109 University Place. Here the library remained for eighty-one years. In 1937, the library moved out and uptown again, to its current location. Sadly, their magnificent building on University Place was demolished, and in 1940 was replaced with the Art Deco apartment building found there today.

The Astor Library was a free public library founded in 1848 and developed primarily through the collaboration of New York City merchant John Jacob Astor, who died that same year, and New England educator and bibliographer Joseph Cogswell. It was meant as a research library, and its books did not circulate. It opened to the public in 1854 on Lafayette Place between Astor Place and Great Jones Street.

By 1879 the library had 189,114 volumes on its shelves. Space was lacking and John Jacob Astor III, grandson of John Jacob Aster, donated three lots of ground adjoining the northern side of the library’s lot for an addition. Both expansions, which opened in 1881, followed the building’s original design so seamlessly that an observer could not detect that the exterior was built in three stages.

The building was abandoned in 1911 and the books were moved to the New York Public Library’s newly constructed branch by Bryant Park. In 1920, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society purchased it, but by 1965 it was in disuse and faced demolition. The Public Theater (then the New York Shakespeare Festival) persuaded the city to purchase it for use as a theater and it was converted by Giorgio Cavaglieri. The building became a New York City Landmark and was designated in 1965.

Benjamin Hazard Field (1814-1893) was a leading philanthropist in New York City during the 19th century. He gave tirelessly of both time and money to some of New York City’s most notable charitable and educational institutions. Field and his family moved into 86 University Place (originally numbered 56, then numbered 50 between 1851 and 1898) around 1843, shortly after the house was built. New York City directories show the family at this location until 1856, when they moved to an elegant mansion on East 26th Street fronting Madison Square Park (demolished).

Field was one of the original founders of the New York City Free Circulating Library (NYFCL), when it was incorporated in 1880, and served as its president from 1885 to 1893. He was key to the NYFCL’s success and rapid growth, extending branches into poor neighborhoods and reaching New York City residents who could not access the private libraries of the day or gain much of any exposure to literature. Under Field’s leadership, the combined circulation of the library’s two original branches rose to 240,000 books per year.

NYFCL partnered with the Children’s Library Association (CLA) assigning a room of the Bruce Library for the exclusive use of children. In 1860, Field was among the founders and initial benefactors of the first women’s library in New York, located at New York University, an enterprise also supported by Horace Greely, Henry Ward Beecher, and Peter Cooper. In 1888, the Jackson Square branch at 251 West 13th Street was opened (extant, Greenwich Village Historic District); the lot, building, and books were all donated by George W. Vanderbilt.

In 1901, the NYFCL’s 1.6 million volumes and 11 branches – including Bond Street, Ottendorfer, and Jackson Square – were absorbed into the New York Public Library. This significantly increased the breadth and reach of the public library system.

57 and 59 Fifth Avenue were built around 1852 by James Lenox (1800-1880), the noted philanthropist and bibliophile whose mansion was located directly south of this building at 55 Fifth Avenue.

His father Robert, a Scottish immigrant, became one of the most successful real estate investors and developers in New York City in the early 19th century and one of its richest men. When he died in 1839, James inherited the family business, as well as 300 acres of property on today’s Upper East Side (the neighborhood now known as Lenox Hill). But by 1845, James Lenox was done with business and retired to pursue his passions of book collecting and building an unrivaled home for himself.

He succeeded wildly in both endeavors. Lenox quickly amassed one of the largest book collections in the country, with a special emphasis on rare books, Americana, and an unsurpassed collection of bibles, including the only Guttenberg Bible in America.

Lenox’s two passions came together when he turned his home at 55 Fifth Avenue into a repository for his ever-growing book collection. The library was, however, kept private, with only the notoriously reclusive Lenox knowing how the books were ordered and where they were kept. Visitors seeking to access the world-renowned private library – which included among other prized items George Washington’s farewell address, all known editions of Milton’s Paradise Lost, and several first editions of Shakespeare’s plays – were typically rebuffed.

Both the Astor and Lenox libraries would struggle financially during the 1870s and 80s. Although New York City already had numerous libraries in the 19th century, almost all of them were privately funded and many charged admission or usage fees. In 1895, along with the Tilden Trust, which was established in the will of Samuel J. Tilden upon his death in 1886 to “establish and maintain a free library and reading room in the City of New York,” the boards of the Lennox and Astor Libraries came together to create “The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations” in order to unify and save their unique and expansive collections. The newly established library would later consolidate with the grass-roots New York Free Circulating Library in February 1901.

And, they say, the rest is history! Notably, the Brooklyn and Queens libraries were never incorporated into the NYPL system because they felt they would not be treated as equals. Famously, Andrew Carnegie donated enough money to fund the purchase of land to construct 65 branches all across Manhattan, many of which still stand today. While the purpose of some of our neighborhoods’ former private and communal libraries have changed, the NYPL that lives on is a reminder of the tireless efforts of our residents to ensure that everyone has continued access to knowledge and that we should never stop questioning and learning.