Thaddeus Hyatt: Trailblazing Greenwich Village Abolitionist and Inventor

Greenwich Village has long been the home of many of New York City’s most radical social justice advocates. With Village Preservation’s interactive map of the Greenwich Village Historic District we can take a virtual walk through the neighborhood to visit the homes of many of these remarkable activists. One recent addition to that map is Thaddeus Hyatt.

In 1854, Hyatt (July 21, 1816 – July 25, 1901), a prominent inventor and ardent abolitionist, built four Anglo-Italianate row houses from 46 to 52 Morton Street in the Greenwich Village Historic District. Hyatt lived with his family at #46. It’s rare to find a Greenwich Village resident who embodied the bohemianism and whimsy of the Village alongside contributing to the unique architectural character and social activism quite as well as Thaddeus Hyatt.

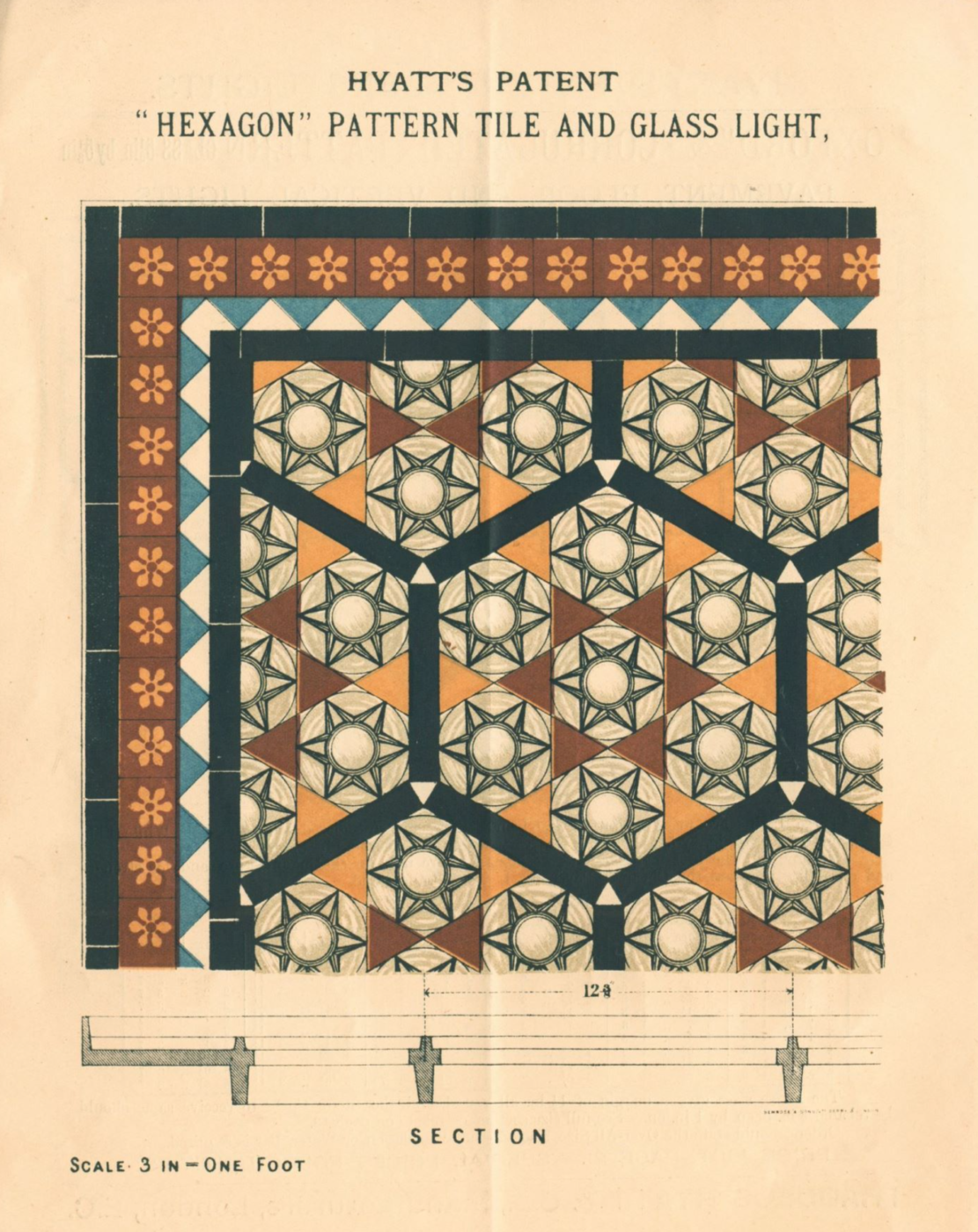

An accomplished structural engineer, Hyatt invented vault lights — glass lenses set into cast iron and/or concrete — which illuminated the basement rooms below. The success of Hyatt’s invention (many of which still dot the sidewalks of SoHo, Greenwich Village, and large sections of Lower Manhattan today) made him quite wealthy, allowing him to commit time and resources to social and political causes. Following the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, which put the legalization of slavery in the hands of the Kansas Territory’s voters, Thaddeus Hyatt became heavily involved in the anti-slavery movement. He was President of the New York Kansas League, an anti-slavery organization that provided support and resources for anti-slavery Kansans in the “Bleeding Kansas” conflict. By July of 1856, Hyatt had been elected President of the National Kansas Committee which raised over $100,000 to support 2,000 new “free state” supporting settlers in the territory. The settlement of Hyattville, Kansas was named for him.

Through his work with the National Kansas Committee, Hyatt became a close friend and supporter of John Brown, a radical abolitionist leader who helped lead free state forces in the Bleeding Kansas conflict. Whenever Brown was in New York City, he made Hyatt’s townhouse at 46 Morton Street his unofficial headquarters. In October 1859, Brown led a raid on a federal armory in Harpers Ferry, Virginia in hopes of inciting a slave rebellion in the southern states. Brown and his party of 22 abolitionists were defeated by the United States Marines. Ten were killed on site, seven were captured, tried, and executed by the United States government, and five escaped. John Brown was captured and found guilty of treason as a result of the raid. Following Brown’s arrest, Hyatt spearheaded a fundraising effort to support John Brown and his family. Brown was executed for his role in raid on December 2, 1859. In the aftermath of Harpers Ferry and John Brown’s execution, Congress learned how much the National Kansas Committee and Thaddeus Hyatt personally offered aid and support to John Brown, and subpoenaed Hyatt to testify before the congressional committee investigating the matter. Hyatt refused to do so, and was jailed in Washington, D.C. from March to June of 1860.

While jailed in Washington, D.C., Hyatt made light of his unfortunate predicament. According to his obituary in the New York Times, “Instead of taking his imprisonment seriously he had his prison room decorated and furnished and then issued invitations to his friends. He never lacked visitors.” Hyatt had checks emblazoned with the jail’s return address printed up, mailed “at home” calling cards to friends and politicians in Washington, and sent out his photograph to various friends complete with a self-important inscription from the Washington Jail. When the Senate completed its investigation into John Brown and Harpers Ferry, Hyatt was released from jail. He quickly wired friends and family in New York with a wry twist on the news: “Have been kicked out; will be home tomorrow.”

Following his release from jail, Thaddeus Hyatt continued to advocate strongly for abolition and remained active in Kansas politics. From 1860-1861, he was instrumental in organizing the Kansas Relief Committee to combat the economic crisis in Kansas caused by the great of drought in 1860. In August 1861, Hyatt was appointed American consul at La Rochelle, France, where he served until 1865. His interest in Europe did not end with the termination of his position as consul, and thereafter he divided his time between the two continents, crossing the Atlantic a total of 43 times during his life. Hyatt moved to London in 1869 and in England became a pioneer in the development of reinforced concrete. Thaddeus Hyatt died in 1901 at the age of 85 at his summer home in the Isle of Wight.

You can explore more about Hyatt and other champions of civil rights and social justice on our Greenwich Village Historic District Map and our Civil Rights and Social Justice Map.