Social Realism in Greenwich Village: The Work of Ben Shahn

Ben Shahn (September 12, 1898 – March 14, 1969) is one of those artists whose work is familiar even to people who may not know his name. For many, he is the quintessential political artist; a classic Social Realist who first gained recognition for the series of 23 paintings he did in the early 1930s,The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti. Shahn’s life and career were largely spent in Greenwich Village.

Ben Shahn once said, “I hate injustice. I guess that’s about the only thing I really do hate.” Born in Lithuania (then part of the Russian Empire) in 1898, Shahn grew up in a family of leftist political activists. When Shahn was only four years old, his socialist father was exiled to Siberia because the Russian government suspected he was a revolutionary. Shahn remembered launching his own sort of protest as a child when he would shout “Down with the Czar!” at anyone wearing a uniform.

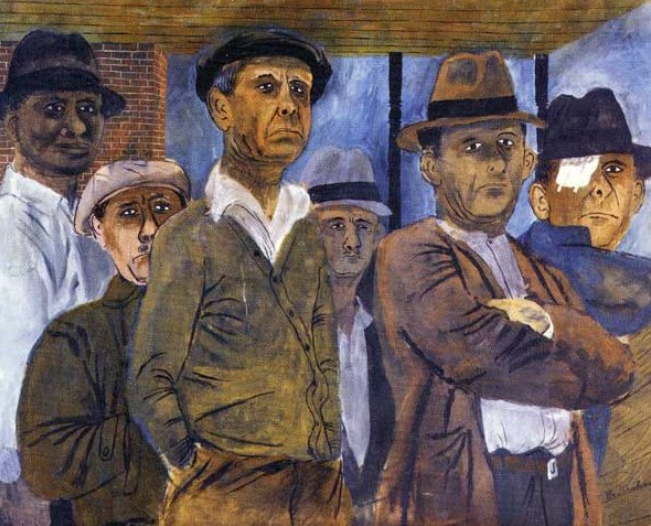

In 1906, the family immigrated to New York and, like many fellow Eastern European Jews, settled in Brooklyn. As an adult, Shahn called himself “the most American of all American painters” because he “came to America and its culture and was sort of swallowing it by the cupful.” Shahn’s Americanism lies in his Social Realist style. Art works in this style are narrative, figurative, and illustrative of the poor, oppressed, or those who live at the margins of society. The guiding spirit of Social Realism is a commitment to humanism. Shahn made paintings, prints, photographs, and drawings that addressed problems like racism, poverty, and oppression. His works are often critical of American life, but by exposing social problems, Shahn hoped to inspire reform.

Shahn had been drawn to the Village by its reputation for social tolerance and progressive politics. There he had easy access to the city’s radical art organizations, as well as to Edith Halpert’s Downtown Gallery, where his work was frequently exhibited. Shahn’s photographs evoke the action of walking through the neighborhood streets, where he used the area’s eclectic architecture to frame his subjects. However, Shahn focused his attention on the residents of the neighborhoods. People sitting on stoops, children playing or reading comics on the sidewalks, and merchants and shoppers of Bleecker Street (the heart of the Italian South Village) were his preferred subjects. These working-class residents interested the artist far more than the neighborhood’s historic sites or bohemian activities.

In 1932 Ben Shahn, his first wife, Tillie (Ziporah) Goldstein, and their young daughter, Judith, moved from Brooklyn Heights into an apartment at 23 Bethune Street. The photographer Walker Evans, the painter and photographer Lou Block, and the film critic Jay Leyda intermittently occupied the street-level workshop, and the painter Moses Soyer lived in a flat above.

Although Shahn moved his family to 333 West Eleventh Street by November 1934, he continued to maintain a studio with Evans and Block at 20–22 Bethune Street.

Shahn’s work resonates today just as much, if not even more than, in his own time. His fearless style, his unflinching eye, and his commitment to social reform through his art are his legacy and his greatness.