The Modernist Jewelry Studios of Greenwich Village

After World War II, the U.S. saw the rise of modernist jewelry: handcrafted jewelry inspired by Cubism, Surrealism and Constructivism. There were two hubs of this movement: San Francisco, which was the home of the Metal Arts Guild, and Greenwich Village. Some of the most noteworthy jewelry designers were people of color, immigrants, and women, which was possible because the barrier to entry for jewelry-making was lower than for other types of art. Between the 30s and the 60s, modernist jewelry studios sprang up all around Greenwich Village, with many concentrated on West 4th Street. The artists and other bohemians who lived in the Village provided a ready audience for “studio jewelry.” According to Toni Greenbaum, “The audience for modernist jewelry was the liberal, intellectual fringe of the middle class, who also supported modern art.” The jewelry maker Art Smith loved the neighborhood and called it “a Little Bauhaus,” because it was a mecca for modern designers, including jewelers who were pioneering what came to be called the Modern Studio Jewelry Movement.

This is the first installment of a multi-part series exploring the many modernist jewelry studios, shops and designers that established themselves in Greenwich Village.

Winifred Mason

Winifred Mason, widely considered the first commercial black jeweler in the United States, was born in 1918 in Brooklyn. She was an exceptional student, earning a bachelors in English literature and a Masters in Education from NYU. For a couple of years, she worked as a craft instructor for the Harlem Boys Club, but teaching didn’t really suit her. So in 1940, she started making jewelry in her apartment out of copper, bronze, and silver.

She sold her jewelry to department stores on Fifth Avenue, which quickly made her work popular. Only a few years after her start, she found she needed to expand to keep up with demand, thus hiring apprentices and opening a studio at 133 West 3rd Street. In 1945, Mason received a grant from the Rosenwald Fund to research folk art and traditional metalworking in the West Indies. That research took her to Haiti, where she met and married artist and jeweler Jean Chenet.

Mason prided herself on making every piece of jewelry differently, only agreeing to replicate a piece if she could make minor variations. She had a long list of clientele that included many famous entertainers and actors, including Billie Holiday. Mason and Chenet split time between New York and Haiti, selling to stores in both locations. In 1948, she opened a store in New York, specializing in Haitian art, jewelry, and fashion. When Chenet was murdered in Haiti in 1963 by the paramilitary Tonton Macoute, Winifred returned to the United States permanently. She passed away in 1993.

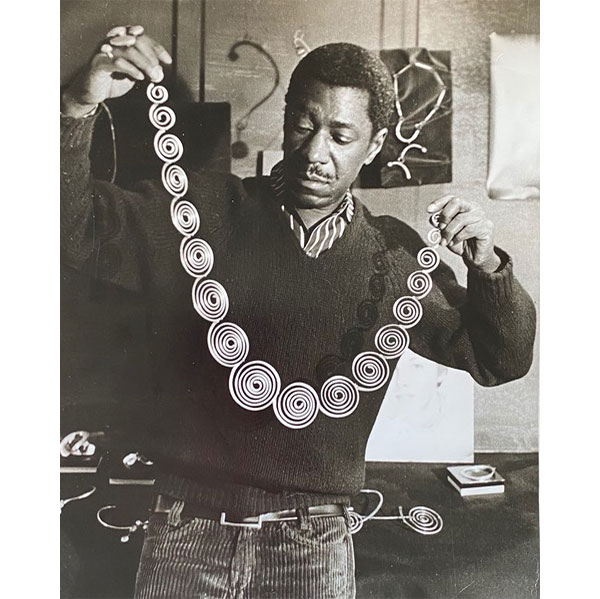

Art Smith

Art Smith, one of the most highly regarded modernist jewelers of the mid-century, started his jewelry career as an apprentice of Winifred Mason. Smith was born in 1917 in Cuba to Jamaican parents, and moved to Brooklyn when he was three years old. He first became interested in jewelry-making while working as a crafts assistant for the Children’s Aid Society.

To strengthen his metalworking skills, he took night courses on jewelry making at NYU, where he met Mason, who became his mentor. At Mason’s studio, Smith cultivated his personal style, inspired by Alexander Calder and traditional African fashion. In 1949, he opened up his first studio on Cornelia Street, but was eventually forced to move around the corner to 140 West 4th Street due to racial tensions.

Smith created unique theatrical pieces, inspired by surrealism and biomorphism. He would often create jewelry for musicians and dancers that he admired. Through these connections, he started to get attention from high fashion magazines, and was commissioned to create pieces for Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue, and the New Yorker. His most famous commissions were a brooch designed for Eleanor Roosevelt and a pair of cufflinks for Duke Ellington (which incorporated the initial notes of Ellington’s renowned track “Mood Indigo” into the design). His studio closed in the late 70’s, a few years before his death. In 2008, he was honored with an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, From the Village to Vogue.

Francisco Rebajes

Before Mason and Smith established their studios, Francisco Rebajes was the very first jeweler to open a studio in Greenwich Village. When he was sixteen, he moved to New York with only $300 in his pocket, leaving his hometown of Puerto Plata in the Dominican Republic. Like Mason, Rebajes was a self-taught craftsman. He lived in a friend’s basement and learned metalwork by tinkering with cans and scrap metal, turning them into animal figurines. In 1932, Rebajes presented his first collection at the Washington Square Park Outdoor Festival. There, Juliana Force, the first director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, saw his work and bought everything for $30.

In 1934, he opened up a small studio at 184 3/4 West Fourth Street. It was a four-foot wide space between two buildings with an improvised roof and a dirt floor. At the beginning, it was rough going. He and his wife slept in the back of the studio on newspapers as bedding. At times, they were so poor, they ate cafeteria food that people left on their plates.

He was known for primarily working in copper, creating jewelry inspired by nature and modern art. His work was included in many exhibitions, including ones at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Brooklyn Museum. He received a bronze medal for his work at the Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques in Paris in 1937 and then a gold medal for his sculptures at the theater in the United States Pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair.

As Rebajes grew in popularity, he upgraded to larger and larger storefronts in Greenwich Village, until in 1942 he opened Rebajes Jewelry and Gifts, an expansive store at 355 Fifth Avenue. This store was known for its avant-garde interior, and boasted an S-shaped counter suspended from the ceiling as its centerpiece. As he grew older, Rebajes became more interested in sculpture than jewelry. Eventually he sold his business and trademark and left the United States for Spain in 1958. There, he continued to make small studio work until his death in 1990.

However, the legacy of the tiny shop at 184 3/4 West Fourth Street didn’t end with Rebajes. ‘The Silversmith’ jewelry store operated for over 60 years at this location, and closed only in 2021. Ruth Kuzub worked there since the 1960s, eventually taking it over as the sole owner. Village Preservation featured The Silversmith in a Business of the Month blog post in 2016. Kuzub ran the store all by herself and made the jewelry for most of those years. She died in 2021, making particularly poignant Kuzub having referred to herself as “the last artist of all the artists that were on the street.”

Further Reading:

- Messengers of Modernism: American Studio Jewelry 1940-1960 by Toni Greenbaum

Very nice article – interesting! Thanks!

I wish I know about this wonderful jewelry years ago – I wonder if any exmples are at MAD – on 59th Street? In her retirement my mother took up jewelry making at the Y on 53rd St and I realize when I look at her work now – that if offered the opportunity in her day – it is something she might have pursued. She was born in 1920. I became an art teacher – so obviously it was in the genes so to speak – we spent many weekends in the museums growing up.