Celebrating Shirley Hayes, Village Activist

“You can help save Washington Square Park. Robert Moses can be stopped. A handful of women did it in Central Park. The bird watchers did it in Central Park. The Washington Square Park Committee has helped hold back the steamrollers in Washington Square Park for six years. BUT an all out effort must be made now to stop Mr. Moses and Traffic Commissioner Wylie from destroying little Washington Square Park by making Fifth Avenue into one of the major traffic arteries of New York City.”

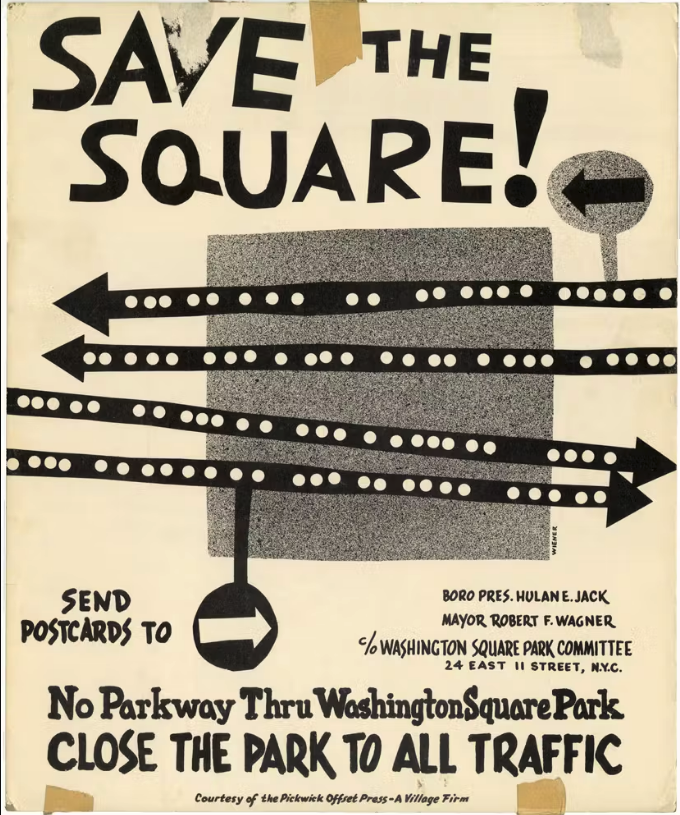

So read a flyer distributed as part of one of the most improbably successful grassroots campaigns our neighborhood has ever seen, “Save the Square!” This effort pitted City Hall, the Board of Estimate, elected officials, the still formidable powerbroker himself, Robert Moses, and New York University (yes, even then, folks!), against a handful of mothers who took their young children to play in the park. They were galvanized by the relentless and uncompromising Shirley Hayes — a former Village Preservation advisor and the subject of an October 20, 2000 oral history with the organization. By the time the campaign proved victorious, it had turned Shirley into a community leader and an inspiration to the many grassroots activists who would follow her example.

The proposal that spurred Shirley into action formed part of a notorious early 1940s plan for a Lower Manhattan expressway. This was intended to link bridges and tunnels to Brooklyn and New Jersey in an ill-conceived effort to reduce traffic. The brainchild of Robert Moses, the scheme would have turned an existing extension of Fifth Avenue that cut through Washington Square Park into a four lane highway that would connect with West Broadway, south of the park, and then feed into the proposed expressway. In doing so, it would have replaced parkland and playground space with roadway. Given Moses’ track record for getting his way, the project was widely regarded as a done deal. But then Shirley came along.

Shirley first learned about the plan in the paper. Outraged at the impact that the project would have on one of the few public green spaces in the neighborhood, she started raising the matter with other mothers at the park and then inviting them to organizational meetings at her house. With no advocacy experience to draw from and lacking a better idea, Shirley and her allies started to just spread the word. They called schools, churches, and civic organizations, most of which did not know about the plan or care much about it, until they heard the particulars. Then, many offered to join the campaign. They had no way of knowing that they were about to embark on a seven year battle against some of the most powerful political figures in city government.

The campaign against the Washington Square Park roadway involved countless hours distributing flyers, gathering signatures, staging demonstrations (with children in strollers in tow), and directing letter-writing campaigns at multiple elected officials. As the group’s ranks grew, political leaders began to pay attention and to look for ways to broker a compromise. The Borough President proposed a buried roadway; and the head of another community group formulated a plan, endorsed by Tammany Hall Democratic leadership, that allowed only limited access to a traffic circle around the Washington Arch. Shirley rejected all of them, earning harsh words from none other than future mayor Ed Koch to the effect that she was turning into a “crackpot” for sticking by the unrealistic goal of a car-free Washington Square Park. And yet, her coalition continued to grow.

Shrley’s allies, organized under the banner of the Washington Square Committee, came to include 36 community groups, consisting of civic organizations, churches, parent-teacher associations, and property owners, among others. The group would collect 16,000 signatures in support of its cause and would earn the support of several newspapers, most notably the Village Voice, as well as, gradually, that of politicians. She herself was appointed to the Manhattan Borough President’s Greenwich Village Community Planning Board to come up with an alternative plan. Her alternative not only did away with the proposed highway, it also converted the 1.75 acres of existing roadway into parkland — a proposal widely welcomed by the community.

In 1958, the relentless efforts of the Washington Square Committee finally paid off. Not only did the City abandon its plans for a Washington Square Park highway, but it agreed to a trial period during which the existing roadway would be closed off to all vehicles except buses. The start of the trial was celebrated with a widely attended “ribbon tying” ceremony. After a subsequent period of evaluation, the City capitulated for good, and Shirley and her allies attained their “unrealistic” goal of a car-free Washington Square Park.

Shirley’s victory not only preserved and expanded Washington Square Park as a historic, green space, it also gave great impetus to the fledgling historic preservation movement that ultimately gave rise to organizations such as ours.

To read or listen to Shirley Haye’s oral history and learn more details about her life and activism, click here. To explore all our oral histories, click here.