Village Preservation Plaques Highlight LGBTQ+ History Throughout Our Neighborhoods

On April 21, Village Preservation joined with the the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project to honor the city’s oldest gay bar and a pioneering event from the early days of the movement for LGBTQ+ rights. The honoree was Julius’ Bar at 159 West 10th Street and the notable event was the Sip-In.

In the 1960s, the New York State Liquor Authority prevented bars from serving alcohol to anyone even suspected of being gay or lesbian, which essentially criminalized LGBTQ+ people from getting together openly. Inspired by the sit-ins taking place in the fight for civil rights in the South, four members of the early gay-rights group the Mattachine Society on April 21, 1966, traveled to various city bars to document the discrimination they faced. Their last stop was Julius’, where they identified themselves as homosexuals to the bartender, who refused to serve them. Members of the local media covered the event, throwing a spotlight on the intolerance the community had to face regularly. It was a key pre-Stonewall action of LGBTQ+ rights that paved the way for making gay bars legal, as well as for further political action. (See photos of the ceremony here and video here.)

The plaque was the 19th posted by Village Preservation (next week, we’ll have our 20th installation). Since our historic plaques program launched in 2012, we’ve honored many other icons that have also played important roles in the greater struggle for LGBTQ+ rights and recognition, including:

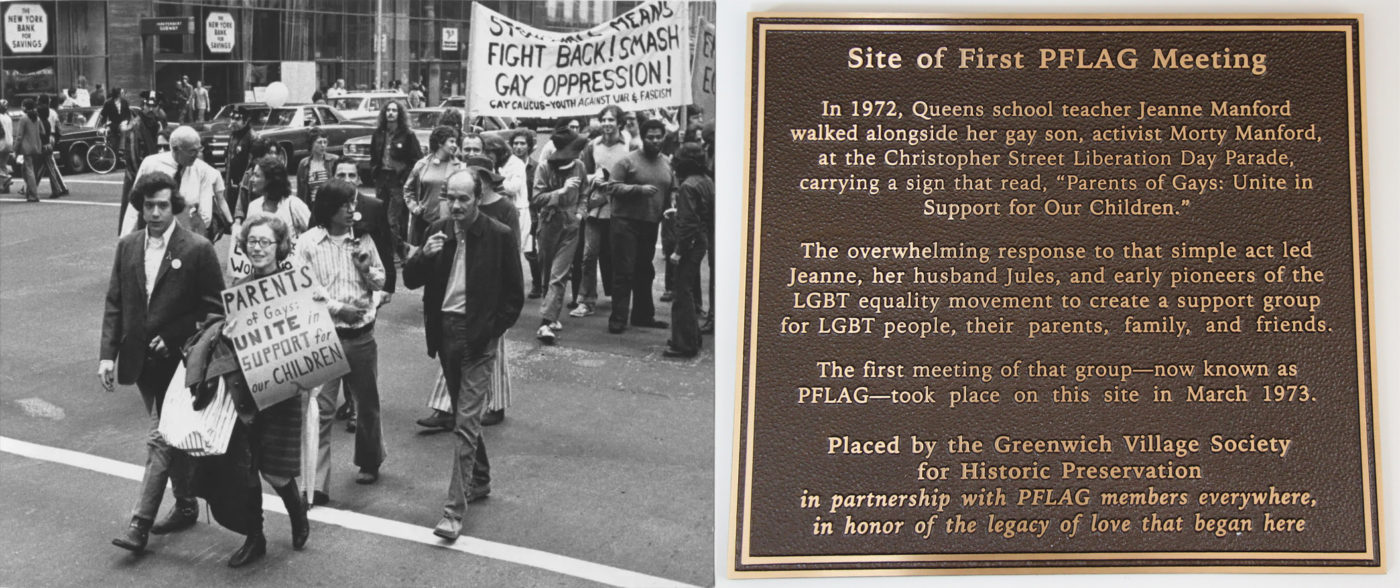

PFLAG

On June 23, 2013, Village Preservation honored the 1973 launch of the group that eventually became Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (PFLAG) with a plaque ceremony at the Church of the Village at 201 West 13th Street. (See photos of the event here.)

The idea for PFLAG began in 1972 when Queens mother and teacher Jeanne Manford marched alongside her gay son Morty in the Christopher Street Liberation Day March, a precursor to the modern-day Pride March. She held aloft a sign that read “Parents of Gays Unite in Support for Our Children” that inspired many gay and lesbian people to run up to Jeanne and beg her to talk to their parents. Instead, she decided to begin a support group that first met at the Duane United Methodist Church (predecessor to the Church of the Village) on March 11, 1973.

In the five decades since that meeting, PFLAG has grown into the nation’s largest family and ally organization, with nearly 400 chapters and 250,000 members and supporters crossing multiple generations of families across America.

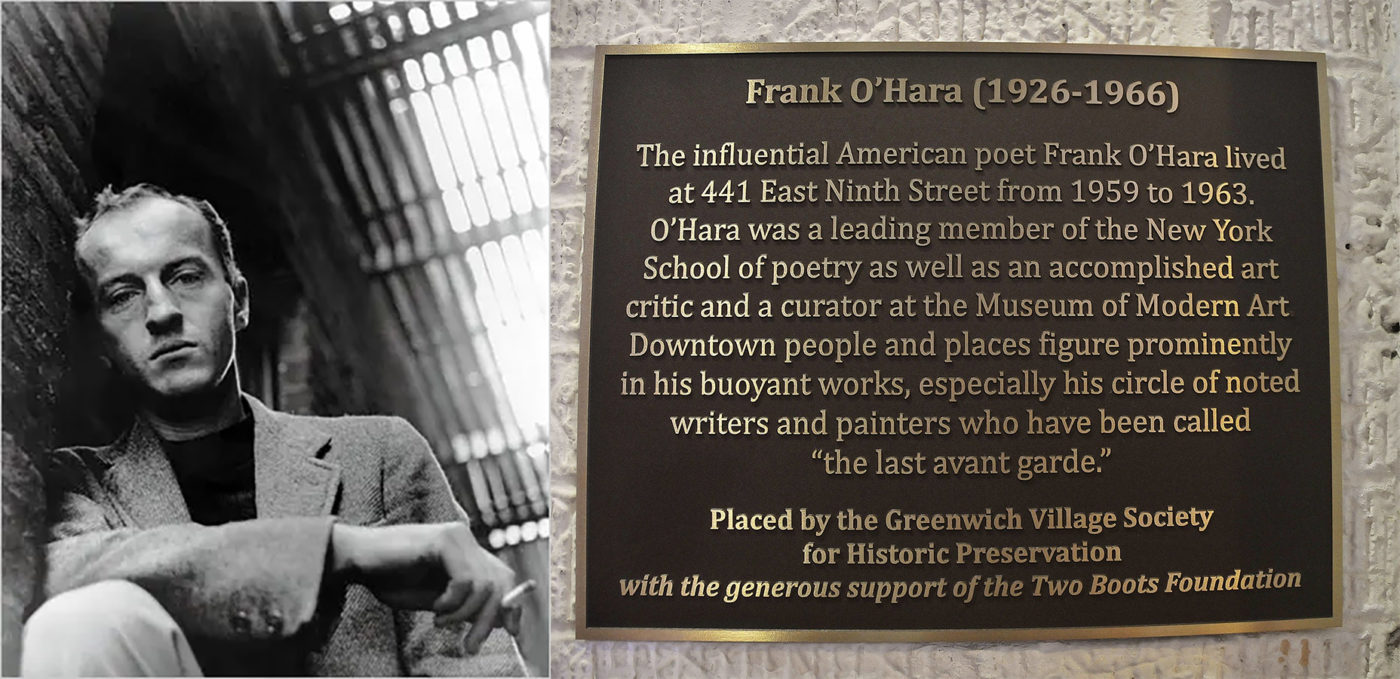

Frank O’Hara

Poet Frank O’Hara lived his entire adult life in New York City, including four years (1959–63) at 441 East 9th Street, where Village Preservation placed a plaque in his honor on June 10, 2014. (See event photos here and video here.)

Born in Baltimore in 1926, O’Hara moved to New York City in 1951. He quickly became a leading member of the New York School, an informal group of poets, painters, dancers, and musicians in the 1950s and 1960s. The city was his muse, and he used that inspiration to write verse on his observations of local life and about his own freedom as a gay man living in a repressive era. His 1954 poem “Homosexuality,” which ends with “‘It’s a summer day, and I want to be wanted more than anything else in the world,’” was published just two years after the American Psychiatric Association listed homosexuality as a sociopathic personality disturbance. As we wrote in a post when the historic plaque was unveiled, “O’Hara seemed to wear his sexuality with a radical lightness, writing poems that reveled in love and sex with the same joie de vivre that he used to write about movie stars, friends, art and artists, booze and cigarettes.”

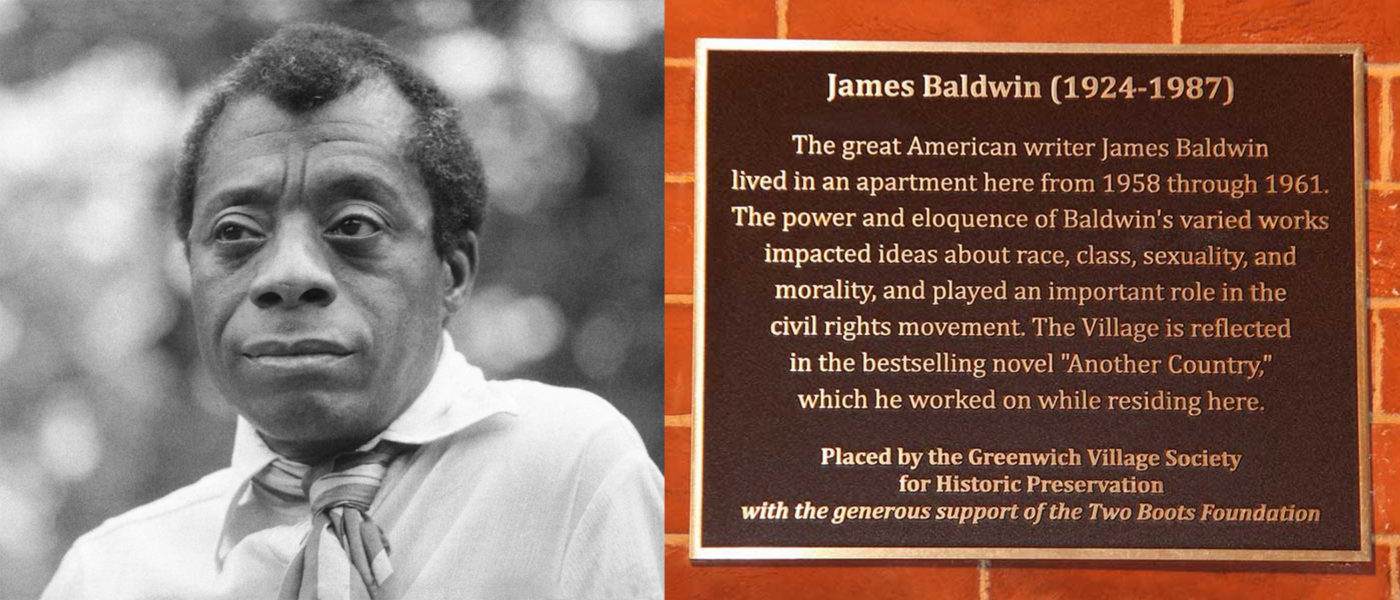

James Baldwin

Born in Harlem in 1924, James Baldwin became a celebrated writer and social critic exploring complicated issues such as racial, sexuality, and class tensions. Baldwin lived much of his life in France, avoiding the discrimination he faced in the United States, but he spent some of his most prolific writing years in Greenwich Village and often wrote of his time here in essays such as “Notes of a Native Son.”

Many of Baldwin’s works address the personal struggles faced by black men and by gay and bisexual men, amid a complex social atmosphere of the 1950s and ‘60s. His second novel, Giovanni’s Room, relates the life of an American man living in Paris and his feelings and frustrations with his relationships with other men. It was published in 1956, well before gay rights were widely supported in America.

Baldwin lived at 81 Horatio Street from 1958 to 1963, where he worked on his third novel, Another Country (released in 1962). Village Preservation installed a historic plaque honoring his history in that building on October 7, 2015. (View photos of the unveiling ceremony here and video here.)

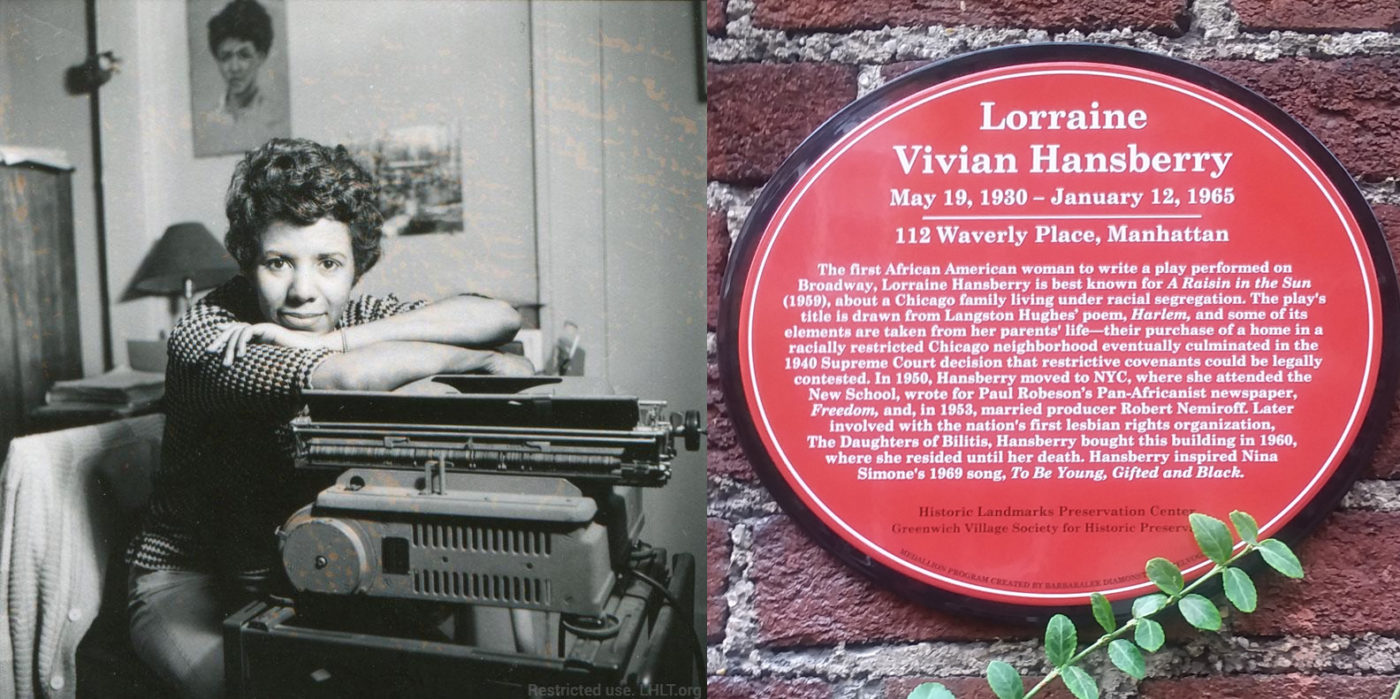

Lorraine Hansberry

Lorraine Hansberry was a playwright and activist most commonly associated with Chicago, but studied at the New School after moving to Harlem in 1951 and lived much of her life here. In 1953, she married Robert Nemiroff and they moved to Greenwich Village, where she wrote A Raisin in the Sun, the first play written by an African American woman to be performed on Broadway. Following the play’s success, she bought and moved to 112 Waverly Place, where Village Preservation unveiled a historic plaque in her honor on October 17, 2017. (Photos here and video here.)

Hansberry separated from Nemiroff in 1957 and they divorced in 1964, though they remained close until her death the following year. Hansberry was a lesbian who had written several anonymously published letters for The Ladder discussing the struggles of a closeted lesbian, as well as simlarly themed short stories for One. She was also a member of the early lesbian rights group the Daughters of Bilitis. Hansberry died of pancreatic cancer at the age of 34.

San Remo Cafe

Village Preservation placed a plaque on the site of this former bar and cafe at 189 Bleecker Street at MacDougal Street in 2013 (see photos here). The San Remo Cafe, which was open from the mid-1920s until the late 1960s, began its life as an Italian-American cafe like so many others in what was then a heavily Italian neighborhood. But by the 1950s it had become one of Greenwich Village’s premiere bohemian hangouts, especially popular with Beat writers and artists. Many of those were gay, and the San Remo came to be known as a place that attracted a mixed but often largely gay crowd.

Among those known to frequent the San Remo were Andy Warhol, Tennessee Williams, Gore Vidal, Jasper Johns, John Cage, William S. Burroughs, Jack Kerouac, W.H. Auden, Robert Rauschenberg, Larry Rivers, James Baldwin, Allen Ginsberg, Terrence McNally, Frank O’Hara, Montgomery Clift, Edward Albee, and Merce Cunningham.