In Memory of Mimi Sheraton (1926-2023), Quintessential Villager

Greenwich Village lost one of its most eloquent voices with the passing of food critic and author Mimi Sheraton (1926-2023). She was a champion of her neighborhood, where she lived for almost 80 years, a friend to Village Preservation, collaborating with us on numerous occasions, and a generous font of knowledge and wit to generations of readers who relied on her to navigate the gastronomic landscape of the city and the world.

Mimi’s fascination with food began early on in her Brooklyn childhood. Conversation at the dinner table primarily entailed either a critical appraisal of her mother’s latest culinary creation or a discussion of her father’s wholesale fruit and produce business. Visits to restaurants were frequent and brought her both to classic Brooklyn establishments, like Kosher delis and Cantonese restaurants, as well as to destination restaurants in “the City.” She moved to the Village in 1945 to go to college, and thus began her love affair with the neighborhood. Her career as a writer would soon follow and turn her into one of the foremost food authorities in town.

The Greenwich Village that Mimi encountered as a college student was, in her words, a dreamy, peaceful neighborhood drawing breath after the conclusion of the war. As she so evocatively captured in her contribution to the Village Preservation-published Greenwich Village Stories, it was a place where famous poets strolling down quiet streets were a common sight, and where people would relax in Washington Square park with the Sunday paper, a sketchpad, or an acoustic guitar. Even as a student, Mimi would arrange weekly outings with Brooklynite schoolmates and hit notable establishments of the period like Sea Fare at the Aegean (8th St.) and Charles French Restaurant (452 Sixth Avenue). By the time she embarked on her career, which began in advertising and proceeded to editorial work at Seventeen and House Beautiful, food had already become her main hobby, involving visits to food markets and restaurants, and the collecting of cookbooks, some in languages she could not even read. A few years later, it would become her profession.

When Mimi started writing professionally, restaurant reviews were not a thing, and would not become one until Craig Cairborne started doing them for the New York Times in 1957. Eventually, though, she started writing them herself on a freelance basis for various publications, including the Village Voice, for which she reviewed some favorite long standing places in the neighborhood, like Coach House (110 Waverly Place) and Rocco’s (121 Thompson St.). On the basis of her reviews for New York Magazine, the New York Times, which had not granted her even an interview when she applied for the post vacated by Clariborne a few years prior, asked her to join the publication. Upon accepting, Mimi became the first female restaurant critic at the Times. There, she set a high standard with her reviews, becoming the most influential critical voice in the industry, and developing a “scare power” that columnist Ken Auletta reports was the envy of none other than Roy Cohn. To prevent those powers from influencing the treatment received at restaurants that she intended to review, she took to wearing disguises and employing stratagems better suited to spy-craft than to food writing. Still, apprehension over her critical verdict was such that some restaurant owners trained their staff to recognize her. On multiple occasions, Mimi arrived, bewigged, bespectacled, and ready to give her assumed name to the host, only to be greeted, to her embarrassment, with a, “How are you this evening, Mrs. Sheraton?”

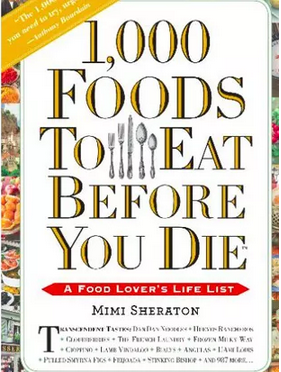

Beyond her work as a reviewer, Mimi was a prolific and far ranging food researcher and writer, doing consulting work for the Four Seasons and Major Food Groups (the group behind Carbone) and writing food and travel features for numerous publications. Several of those assignments took Mimi all over the world, a good fortune occasionally of her own making. She would decide where she wanted to go and then pitch a story that would send her there. The experiences and insights gleaned during these travels made their way into some of the dozen plus books that she published. They resurface to great effect in her last one, 1,000 Foods to Eat Before You Die, a dazzling expression of Mimi’s belief that food offers a great handle by which to pick up another culture.

Closer to home, Mimi’s oeuvre provides a window into the dramatic transformation that the city’s relationship to food and restaurants underwent over the past half century. In a conversation we co-hosted for the New School’s Gotham on a Plate conference, she personally shared her thoughts on that trajectory, offering commentary on the cooking-from scratch impetus of the 70s, the restaurant boom of the 80s, the dramatic increase over the past few decades in local access to previously unavailable (and unheard of) ingredients. She also called attention trends she anticipated (Nordic cuisine), trends she deplored (kale), and trends still to come (Southeast Asian / Latin American fusion!). You can watch the fascinating conversation in its entirety here.

If one topic vied with food for Mimi’s attention, it was her beloved neighborhood. A diehard Villager who referred to trips uptown as defections and who, upon repatriation, found “Waverly air” easier to breathe, Mimi experienced great comfort in her brownstone of almost sixty years and joy all around her: in the human scale and pedestrian vitality of the streets, in the local wildlife, in the neighborly feeling of her block, and yes, in the area’s dynamic restaurant scene. A committed preservationist, she kept inventory of painful losses — a ever growing list that comprised pleasantly serviceable family restaurants, independent bookshops, small galleries, and cherished buildings — while at the same time celebrating and defending the neighborhood’s cultural and architectural legacy. She was ever ready to extol the virtues of her surroundings, be it the sparkling Gothic lines and stained glass of Grace Church, the secluded charm of Patchin Place, or the vestiges of the Village’s bygone country character. Mime recognized that the neighborhood had changed and lamented, for instance, the proliferation of chain stores and of absentee owners (including those who take off for second or third homes for months at a time). And yet, through those changes, she still managed to see the Village as it once was and to hold on to the local myth that drew her there all those years ago. At the time, she was told that it was a neighborhood that you grew out of. Upon celebrating half a century there, Mimi took stock of the historic, leisurely, romantic, contentious, and young-spirited air of the Village and declared that she would neither move out nor grow up until she was beyond choosing. Now that the choice has been taken from her, we bid her farewell. The city, Greenwich Village, and all of us at Village Preservation will miss her dearly.

If you would like to learn more about Mimi’s life, you can do so from Mimi herself, in the oral history we did with her in 2019. It can be found here.