O Pioneers! Two Remarkable Women of Bank Street: Willa Cather and Lucy Sprague Mitchell

Women’s History Month gives us yet another opportunity to celebrate the marvelous and groundbreaking women who have lived and worked in our neighborhoods. Today we look at two pioneering women who lived and worked on Bank Street: Willa Cather and Lucy Sprague Mitchell.

Bank Street

Many of our streets are beloved by their residents and have storied and rich pasts, not to mention exquisite charm. But few have been home to such a variety of luminaries who thread themselves so intensely through the city’s social, economic, cultural, and political fabric as Bank Street.

As Roberta Brandes Gratz, the author of “The Battle for Gotham: New York in the Shadow of Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs” wrote, “Bank Street is the quintessential Jane Jacobs Greenwich Village block, the quintessential urban street” (Jacobs herself lived just feet away from Bank Street, on Hudson between Perry and 10th). It is no wonder then that Bank Street has often been a beacon for writers, artists, and intellectuals of all stripes.

First, let’s just put to rest questions about how Bank Street got its name; a question that comes up often, since it is now a quiet, primarily residential street. It’s pretty simple. During the 1798 outbreak of yellow fever in downtown Manhattan, The Bank of New York — the oldest bank in the United States, founded by Alexander Hamilton — began a trend of banks moving temporarily northward to escape the disease. The Bank of New York was the first to move to the “suburb” of Greenwich Village, but subsequent epidemics in 1803, 1805, and 1822 pushed other banks, such as Bank of the Manhattan Company and Phenix Bank, to the same block where the Bank of New York was located. This cluster of businesses led to the naming of the previously unnamed lane “Bank Street.” The bank structures have been since demolished, but the street name remains.

Willa Cather

The great American writer, Willa Cather, made her home in Greenwich Village for most of her illustrious career. The place that Cather probably most considered “home” in New York City and the one that coincided with the most prolific period in her career, was her spacious and comfortable apartment at 5 Bank Street, a five-story brick house, much like others still existing on the block. Cather and her life partner Edith Lewis moved to #5 Bank Street in 1913. It was in this brick house that Cather completed some of her most critically acclaimed books and stories. Her novels O Pioneers! (1913) and My Antonia (1918) which explore the stories of immigrant pioneers in Nebraska were written here. She won the Pulitzer Prize in 1922 for her novel One of Ours, which depicts a Nebraska native who goes to fight in WWI. In 1927 she published what is widely considered to be her masterpiece, Death Comes for the Archbishop.

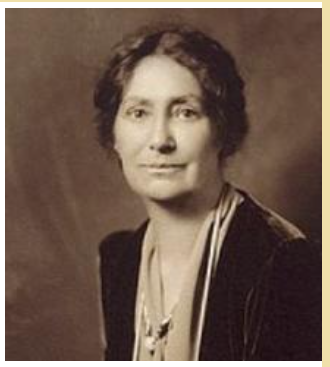

Lucy Sprague Mitchell

While Cather was a pioneer in American liturature, Lucy Sprague Mitchell was an educational pioneer of the first order. Readers who know of the groundbreaking educational institution The Bank Street School for Children, and the Bank Street College of Education might wonder why they are called Bank Street, given that the school and the college are both located on the Upper West Side of Manhatten. This venerable institution was founded by Lucy Sprague Mitchell and flourished and grew right here in the Village on Bank Street.

In 1916, educator Mitchell and her colleagues, influenced by revolutionary educator John Dewey and other humanists, concluded that building a new kind of educational system was essential to building a better, more rational, humane world. The Bureau of Educational Experiments (BEE) was founded by Mitchell with her husband, Wesley Mitchell, along with colleague Harriet Johnson. Their purpose was to combine expanding psychological awareness with democratic conceptions of education. With a staff of researchers and teachers, the Bureau set out to study children—to discover what kind of environment best suits their learning and growth, then create that environment and train adults to maintain it.

In 1930, the Bureau of Educational Experiments moved to 69 Bank Street and set up the Cooperative School for Student Teachers, a joint venture with eight experimental schools to develop a teacher education program that produced, and still produces, teachers dedicated to stimulating the development of the whole child.

Mitchell recognized children’s need to learn through play and direct experience. A leader in the child study movement, Mitchell saw herself as an experimentalist. In addition, she democratized progressive education by spreading its ideals through teacher education and the development of children’s writers.

It is interesting to note that the laboratory school was the initial model for the 1965 Head Start program.

IN 1937 Mitchell set up a Division of Publications to produce books for and about children. The Writers Lab—a workshop connecting professional writers and students of the Cooperative School for Teachers—was formed. Early Writers Lab members include Ruth Krauss, Edith Thacher Hurd, and none other than Margaret Wise Brown, author of Goodnight Moon, whose cottage at 121 Charles Street remains one of the most eccentric, curious, and delightful structures in the Village.

As a side note, it is interesting that Bank Street once was a thoroughfare. Village Preservation has recently come to acquire a photo from an interested resident of Bleecker Street that depicts the area when Bank Street went all the way to Bleecker before the Bleecker Playground was built.

Anchoring that corner in the early 20th century was the formidable Henry I. Stetler brick warehouse. (Beside it is a bandstand-turned-comfort station.) In 1927, a significant fire raged through the Stetler warehouse, injuring dozens of firefighters and causing the city to condemn the building. The warehouse was razed in the 1950s.

The Bleecker Playground opened in 1966 and stands in the spot where Bank Street once met Bleecker Street.