James Baldwin Leaves an Enduring Legacy in Greenwich Village

“For, while the tale of how we suffer, and how we are delighted, and how we may triumph is never new, it always must be heard. There isn’t any other tale to tell, it’s the only light we’ve got in all this darkness.”

-James Baldwin, “Sonny’s Blues”

James Baldwin (August 2, 1924 – December 1, 1987) was a novelist, essayist, playwright, poet, and social critic. His first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, was published in 1953 to great acclaim, and his essays, Notes of a Native Son and The Fire Next Time were bestsellers that made him a critical figure in the growing civil rights movement of the 1960s. He lived and worked in and around Greenwich Village during some of his most creatively productive years.

Born and raised in Harlem, Baldwin moved to Greenwich Village in 1943. He first stayed with modernist painter Beauford Delaney at his 181 Greene Street apartment/studio (now demolished). Delaney, who was Black, gay, and earning a living as an artist, mentored the young writer and introduced him to diverse cultural perspectives as well as to a variety of people who would play large roles in shaping Baldwin’s life and career.

One of those introductions was to Connie Williams, the owner of Calypso, a small restaurant at 146 MacDougal Street (now demolished). It was a space where races mixed freely, which was still unusual at the time, and on any given night you might have seen Paul Robeson or Henry Miller eating side by side with Burt Lancaster or Malcolm X. Baldwin worked there as a waiter and became acquainted with a racially diverse group of artists and political radicals. Baldwin also frequented such Village mainstays as the San Remo Cafe, Minetta Tavern, Joe’s Diner, and the White Horse Tavern. As a Black man, he often dealt with racial discrimination in these places, particularly, in his words, at the San Remo.

In 1948, Baldwin left for Paris in an attempt to escape the ever-present racism he endured in New York City, although he would frequently return to New York to write and find further inspiration for his work. Upon each of his returns to the city, he lived in several places in the Village, including a small apartment on Gay Street in 1955 with the Swiss painter Lucien Happersberger, whom he met in Paris. He lived for the longest at 81 Horatio Street, where he rented an apartment from 1958 until 1961. There, he befriended Sam Floyd, a Black schoolteacher and journalist who also lived on Horatio Street, and at Floyd’s apartment, he spent time with other Black writers and musicians like Nina Simone, Max Roach, and Nikki Giovanni.

On Horatio Street, Baldwin continued work on his third novel, Another Country (1962), which he had begun in 1948. The book, set in late 1950s Greenwich Village, included vivid descriptions of life in the Village:

“They reached the park. Old, slatternly women from the slums and from the East Side sat on benches, usually alone, sometimes sitting with gray-haired, matchstick men. Ladies from the gigantic apartment buildings on Fifth Avenue, vaguely and desperately elegant, were also in the park, walking their dogs; and Negro nursemaids, turning a stony face on the grown-up world, crooned anxiously into baby carriages. The Italian laborers and small-business men strolled with their families or sat beneath the trees, talking to each other; some played chess or read L’Espresso. The other Villagers sat on benches, reading – Kierkegaard was the name shouting from the paper-covered volume held by a short-cropped girl in blue jeans – or talking distractedly of abstract matters, or gossiping or laughing; or sitting still, either with an immense, invisible effort which all but shattered the benches and the trees, or else with a limpness which indicated that they would never move again.”

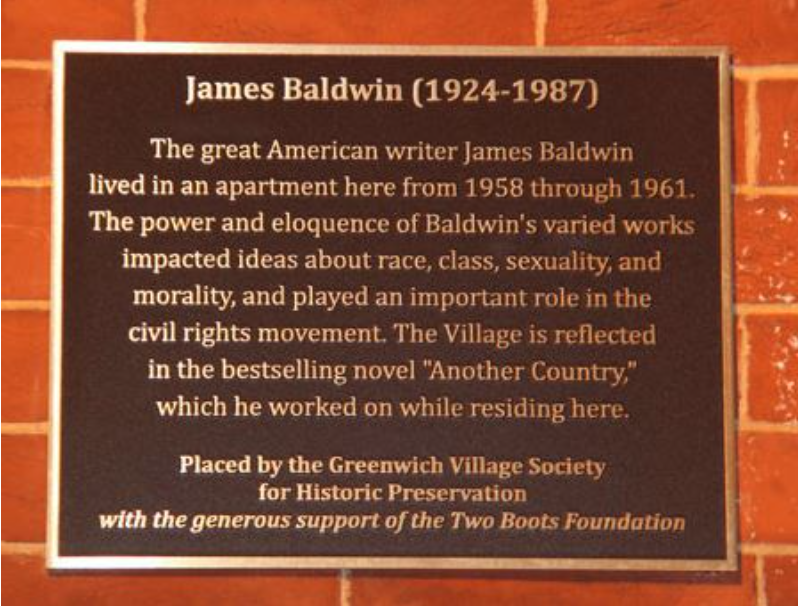

In 2015 Village Preservation commemorated Baldwin’s time in the Village with a plaque at 81 Horatio. You can view the video here.

In her intro to James Baldwin’s Nothing Personal, Dr. Imani Perry wrote:

“Baldwin walked through city streets looking at people. I’m doing the same these days. I’m writing in the time of COVID, a season during which most of us are wearing masks. As a result, with only glimpses at flared nostrils or fake smiles, our eyes are even more exposed. They are, as Baldwin told me to expect, exhausted and terrified. They scan and they disappear into worry. They are also more luminous in their nakedness. My overview of the public is limited though. Fewer people are out these days, because public spaces pose an immediate danger. And it is easy to navel gaze, to see our adversity, terror, exhaustion, and worry as private suffering. But as Baldwin once said, reading allows us to recognize each other. It is nothing personal. It makes everything seem possible. May we find hope in his brilliant words.”

Baldwin’s ability to craft a story that is at once heartbreakingly, devastating, and daringly hopeful is one of his many enduring legacies. His innumerable contributions to literature and culture have inspired generations to continue fighting against violence and injustice in America. VILLAGE VOICES II, Village Preservation’s outdoor public history, and art project aims to amplify James Baldwin’s enduring wisdom so that others may also find inspiration in his life and legacy, and will include him, as it did in the 2021 VILLAGE VOICES, along with more then twenty other luminaries of art, literature, civil rights, and other fields from our neighborhood.

The life and work of James Baldwin will be on display in September as part of our 2022 Annual Benefit: VILLAGE VOICES. Our benefit will feature an engaging installation of exhibit boxes displayed throughout our neighborhoods featuring photographs, artifacts, and recorded narration that will provide entertaining and illuminating insight into the momentous heritage of the Village.