Pioneers Converge on MacDougal Street: Dr. Robert Hogan, Rev. Henry Highland Garnet, and Sarah Smith Garnet

Emerging from the quaint MacDougal Alley, one of the first buildings one sees is the four-story row house at 175 MacDougal Street. Tucked between two taller structures, the building stands out with its delicate Federal-style wrought iron balconies, its handsome arched doorway, and its blind bulls-eye window just above. But this gem of the Greenwich Village Historic District holds far more history than is visible upon first glance. It was built by one of the the foremost leaders of the mid-19th century Irish community, who developed a leading aid society that transformed the experience of immigrating from Ireland and chartered a trailblazing bank. Just under a half-century later, No. 175 MacDougal Street became home to two groundbreaking members of the city’s African American community, who advocated for abolition and suffrage in and beyond the Village. One was the first African American to address the U.S. House of Representatives, and the other was the first African American woman principal in the New York City school system.

Dr. Robert Hogan

Dr. Robert Hogan (b. August 23, 1800, according to the only source we found with this information) was a leading figure in the city’s Irish community in the mid-19th century. Hogan attended Trinity College in Dublin, Ireland, and later moved to New York City where he built 175 MacDougal Street in 1837. He later lived at 3 St. Clement’s Place (which became 179 MacDougal Street; now demolished), and owned 5 St. Clement’s Place (which became 181 MacDougal Street; also demolished).

From 1839 to 1842, Hogan served as president of the fraternal and benevolent society The Friendly Sons of St. Patrick (founded 1784). As part of his work, Dr. Hogan was in charge of coordinating the organization’s early St. Patrick’s Day parade, and developing a leadership team for the newly-formed Irish Emigrant Society. Responding to the large number of Irish immigrants arriving in New York City in the 1830s, the Irish Emigrant society was founded on March 22, 1841, and offered protection to those who had recently emigrated. The aid society went on to establish offices on Wall Street, Nassau Street, Maiden Lane, Merchants’ Exchange, and Fulton Street — close to the city’s commercial center. Dr. Hogan served as the first vice president of the Society, and for a time acted as its president.

The Irish Emigrant Society would station representatives at the Battery (when the Battery’s Castle Clinton was the city’s immigration processing center, before Ellis Island) to meet people immediately upon their arrival to New York and provide assistance to those who were stopped by the Immigration Authority. It also helped recent immigrants from Ireland find employment and evade fraud, and offered general advice and information to assist the immigration process. According to a calculation reported in the Society’s 1899-1900 Annual Report, most of those who registered with the Society ended up staying in New York. To fund its efforts, the Society organized an annual ball, and relied on five dollar annual subscriptions and members’ donations. The Society’s widely successful model was replicated in other cities across the country, including Philadelphia and New Orleans.

In 1850, following the waves of Irish immigration instigated by the Irish Famine, the Irish Emigrant Society made history again when it chartered the Emigrant Savings Bank. The Bank gave immigrants a safe place to keep their money and assisted individuals with sending funds back to their relatives in Ireland. Throughout its history, the Emigrant Savings Bank shared officers with the Emigrant Society, and the two organizations maintained close connections. The Emigrant Savings Bank, still operating, is the oldest savings bank in New York City and was once the largest savings bank in America. Today it is the largest privately held, family-owned and run bank in the country.

Reverend Henry Highland Garnet

Four decades after Dr. Robert Hogan constructed his house at 175 MacDougal Street, yet another venerable local community leader would make his home in this very same building: the groundbreaking abolitionist, minister, educator, and orator Henry Highland Garnet. Garnet moved to MacDougal Street after living in a number of residences in our neighborhoods, including 183 Bleecker Street, 185 Bleecker Street, and 102 West 3rd Street. Hogan remained at 175 MacDougal Street from 1879 until shortly before his death in 1882.

Henry Highland Garnet was born into slavery in Maryland in 1815, but when he was about nine years old his family was granted permission to attend a funeral and used the opportunity to escape to Delaware, and then to New York City. Garnet, who attended the African Free School and the Phoenix High School of Colored Youth, began his career in abolitionism at an early age. While living with his family in Troy, New York, he worked as the pastor of the Liberty Street Presbyterian Church for six years, publishing papers on religion, abolitionism, and the temperance movement. Afterwards, he moved to New York, joining the American Anti-Slavery Society and speaking at abolitionist conferences. Garnet believed that negotiating abolition would have limited success, and in his 1843 “Address to the Slaves” Garnet urged slaves to rise up against their masters. By 1849, he assisted Black individuals seeking to move to Mexico, Liberia, and the West Indies. He also endorsed Black Nationalism in the United States.

From 1859 to 1863, and again from 1873 to 1882, Henry Highland Garnet served as the leader of the Shiloh Presbyterian Church, one of many African American churches once found in Greenwich Village, when nearly all the city’s leading African American churches were located in this neighborhood. Under Henry Highland Garnet’s leadership, the Shiloh Presbyterian Church was at the center of the anti-slavery fight, leading boycotts of sugar, cotton, and rice, which were all products of slave labor. Garnet collaborated with local newspapers to spread the abolitionist cause, and when John Brown was hung for inciting an armed slave uprising in Virginia on December 2, 1859, Garnet organized a memorial service at the Shiloh Church. Then, when the 1863 Draft Riots erupted, and hundreds of white working-class men launched racist attacks on the city’s Black residents and businesses, Garnet and his church stepped in to help those who were impacted. As an appointee of the Committee of Merchants for the Relief of Colored People Suffering from the Late Riots, Garnet worked with other Black ministers to complete three thousand visits to the homes of individuals and families seeking aid.

In the final weeks of the Civil War, on February 12th, 1865, Garnet became the first African American to address the U.S. House of Representatives, at the invitation of President Lincoln on the president’s birthday. He delivered a sermon that honored the successes of the Union Army and the effort to abolish slavery.

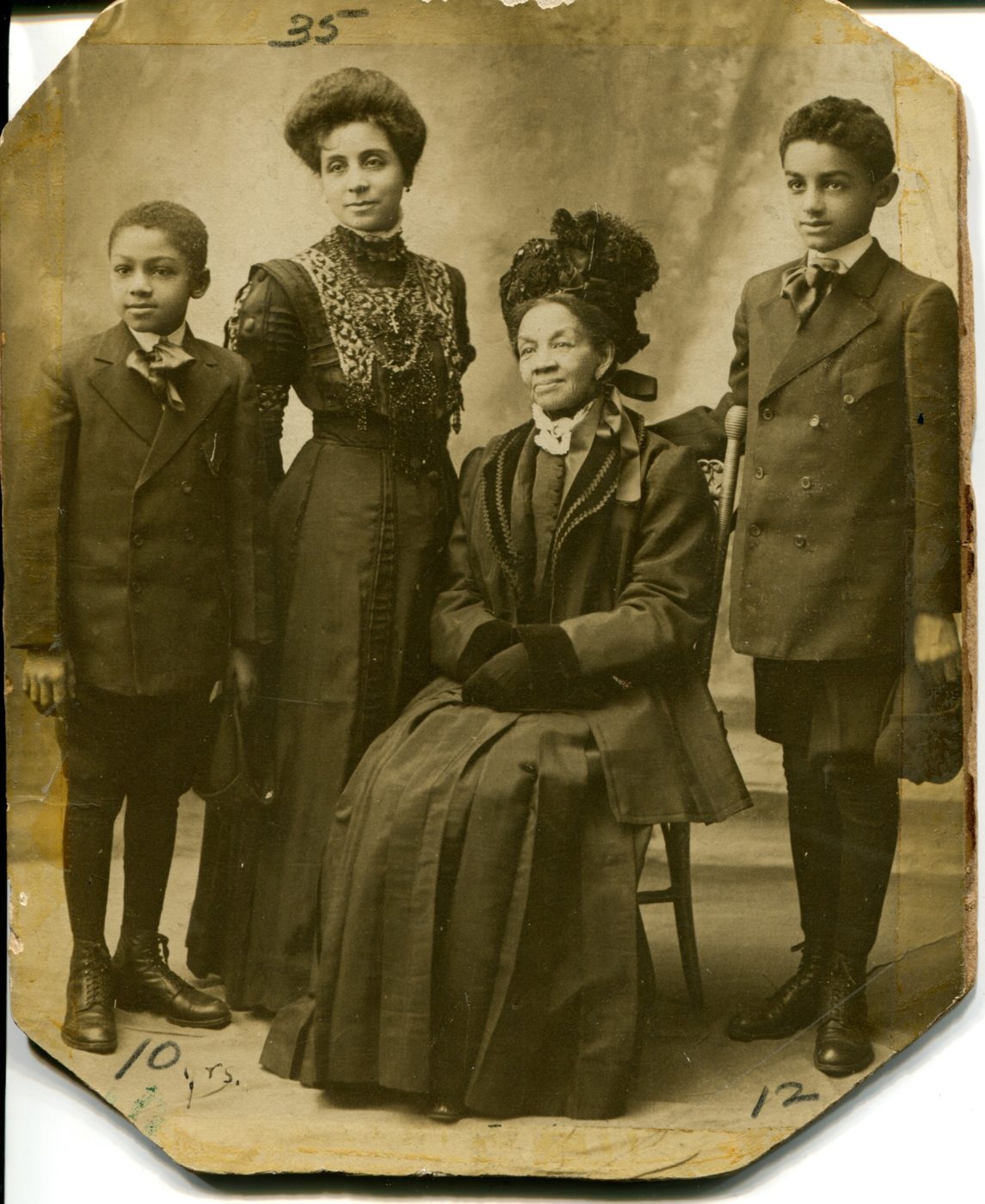

Sarah Smith Garnet

Henry Highland Garnet’s wife, Sarah Smith Garnet, was also a highly notable champion of abolitionism and women’s suffrage, and lived with her husband at 175 MacDougal Street. Sarah Smith Garnet was born on July 31st, 1831 to parents who owned land in Queens County, then part of Long Island. Her father, Sylvanus Smith, was a founder of the free Black community of Weeksville, in present-day Crown Heights. Her sister, Susan Smith McKinney Steward, was the first African American woman physician in New York, pioneering a legacy of women in medicine along with Villager Elizabeth Blackwell.

On April 30, 1863, Sarah Smith Garnet became the first African American woman principal in the New York City school system, for which she worked for 37 years. When she began teaching in 1854, the public schools were racially segregated, including her school, the African Free School of Williamsburg. Today, the Sarah Smith Garnet school, P.S. 9, is located in another historic district — Brooklyn’s Prospect Heights.

From 1883 to 1911, Garnet also owned a seamstress shop in Brooklyn. During that time she co-founded the Equal Suffrage League, the first suffrage organization founded by and dedicated to the suffrage of Black women. For its first few years, the organization met in the seamstress shop, then moved to the YMCA on Carlton Avenue, and later merged with the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs. The Equal Suffrage League worked with the Niagara Movement, a predecessor to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

In 1892, Garnet participated in establishing the Woman’s Loyal League of New York and Brooklyn with Ida B. Wells, Susan McKinney, Maritcha Lyons, and Victoria Earle Matthews. In July 1904, she spoke at the fourth convention of the National Association of Colored Women in St. Louis, Missouri. Garnet was also elected superintendent of the suffrage department of the organization, which joined forces with the National Council of Women in 1905. Although Sarah Smith Garnet passed away in 1911, nine years before the passage of the 19th Amendment, which removed sex as a barrier to voting rights in this country, her impact was most certainly a powerful catalyst for change in her community.

In 1911, Garnet accompanied her sister, Susan Smith McKinney Steward, to London, England, for the first Universal Races Congress. Steward presented the paper “Colored American Women” at the conference, which was also attended by W.E.B. Du Bois. Just weeks after she returned from Europe, Garnet died at the age of 88, leaving behind a legacy of education and activism that would, just a few years later, result in the success of women’s suffrage in 1920.

For more information on other Immigrant and African American leaders and landmarks in our neighborhoods, check out the “Immigration Landmarks” and “African American History” tours on our interactive map: