#SouthOfUnionSquare, the Birthplace of American Modernism: Elizabeth Olds

“South of Union Square, the Birthplace of American Modernism” is a series that explores how the area south of Union Square shaped some of the most influential American artists of the 20th century.

The area south of Union Square, which Village Preservation has proposed be designated an historic district, has attracted painters, writers, publishers, and radical social organizations throughout the 20th century. The neighborhood birthed a namesake social realist art movement — the Fourteenth Street School — and later hosted a number of influential artists and movements like Abstract Expressionism, the Ninth Street Five, and “The Club.” Art, politics, industry, commerce, the New York elite, and the working class collided to create an eclectic culture and built environment in this neighborhood that helped shift the center of the global art world to New York City.

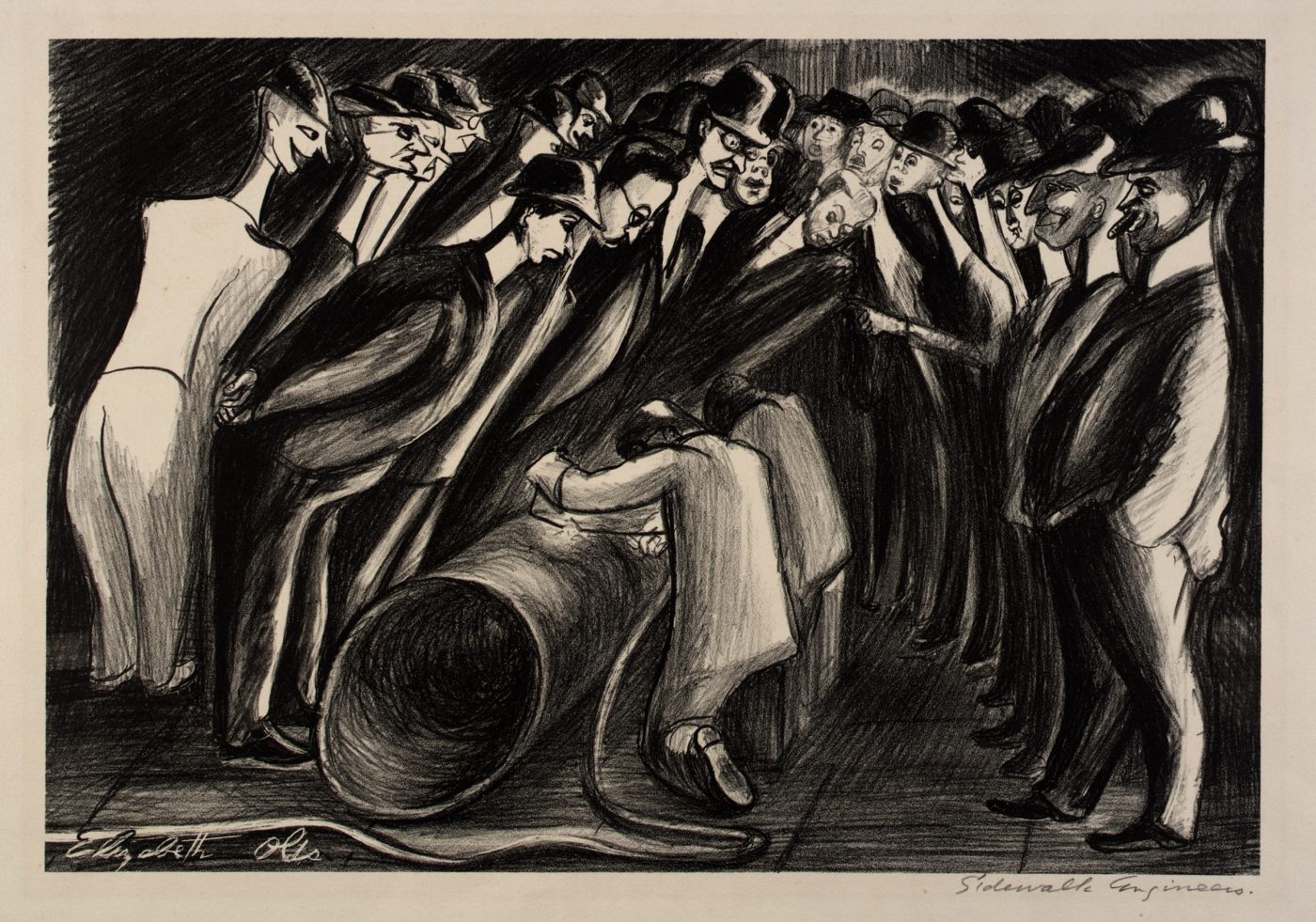

Elizabeth Olds (December 10, 1896 – March 4, 1991) was an American artist known for her work in developing silkscreen as a fine arts medium. From the late 1930s to the late 1950s, Olds’ studio was located in the neighborhood South of Union Square at 53 East 11th Street. She was a painter, illustrator, and printmaker who was particularly skilled in silkscreen, woodcut, and lithography processes. Born and raised in Minneapolis, Minnesota, Olds was awarded a scholarship to study at the Art Students League under George Luks, a founder of the Ashcan School. Olds was introduced to social realist subject matter while on sketching trips with Luks on the Lower East Side. Elizabeth Olds artistic promise was honored in 1926 when she was the first woman to be awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship. She used the funds from the fellowship to study painting.

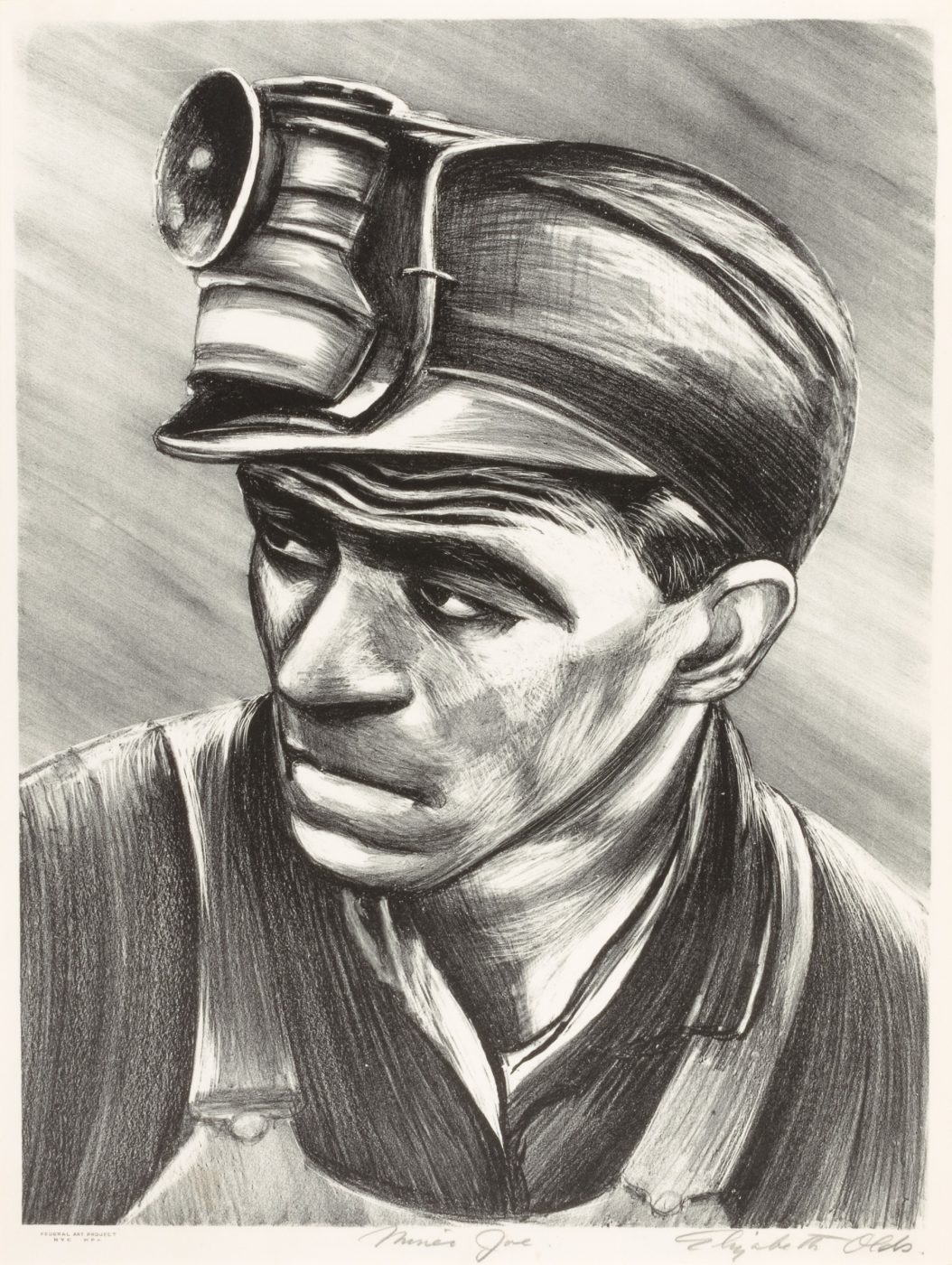

When Olds returned to the United States in 1929, the Great Depression was just beginning, and the political events of those years would shape her artistic practice forever. In 1932, she saw José Clemente Orozco’s new murals at Dartmouth College, and vowed to incorporate more political themes into her work. She found great success in this once she began working with the Works Progress Administration-Federal Art Project in Omaha, Nebraska around 1935. Through her work with the WPA-FAP, she trained younger artists on silkscreen techniques and successfully elevated the practice of silkscreen to fine art with her award-winning print Miner Joe (1937). Olds’ use of silkscreen and interest in printmaking was also reflective of her leftist politics. Through the ability to create multiples of a piece, art collecting was made more accessible to working people, as evidenced by her inclusion in the 1940 Museum of Modern Art Exhibition American Prints Under $10.

Later in her career, Elizabeth Olds was awarded artist-in-residence fellowships at the MacDowell Colony and Yaddo Artist Retreat. There is no question that the neighborhood South of Union Square’s connection to labor and leftist politics made an indelible mark on Elizabeth Olds’ artistic practice. By renting a studio in this neighborhood, she was able to create a community of like-minded artists and become involved in some of the most consequential leftist organizations of the 20th century.

Village Preservation’s proposed South of Union Square Historic District was recently named one of 2022-2023’s “Seven to Save” — the biannual list of the most important endangered historic sites in New York State — by the Preservation League of New York State. This designation shines a spotlight on the incredibly valuable and varied architecture of this neighborhood, and its deep connections to civil rights and social justice history as well as transformative artistic, literary, and musical movements.

To learn more about the neighborhood, check out our new and frequently updated South of Union Square Map and Tours. We have received a series of extraordinary letters from individuals across the world expressing support for our campaign to create a historic district for the neighborhood South of Union Square. To help protect these incredible historic structures and other buildings in this neighborhood, click here.