(Even More) Civil Rights and Social Justice Champions in Our Neighborhoods

Village Preservation has long made a priority of elevating, preserving, and celebrating the histories and contributions of underrepresented and marginalized communities in our neighborhoods. We also advocate for policies for our neighborhoods that promote racial and socio-economic diversity. As part of these ongoing efforts, Village Preservation maintains a Civil Rights and Social Justice Map, which holds about two hundred sites throughout Greenwich Village, the East Village, and NoHo. Expanding this interactive map resource is a collective effort, and we encourage the public to share locations where civil rights and African American, Women’s, LGBTQ, Latinx, Asian American, and other social justice history has been made in our neighborhoods. Recently, we have added the homes of a groundbreaking Black theater company, a lawyer who paved the way for marriage equality, and another lawyer who pursued some of the most defining civil rights cases of the 20th century.

The Negro Ensemble Company, 35 St. Mark’s Place/133 Second Avenue

In 1965, playwright Douglas Turner Ward (May 5, 1930 — February 20, 2021), producer/actor Robert Hooks (b. April 18, 1937) and theater manager Gerald Krone (February 25, 1933 — February 20, 2021) developed the Negro Ensemble Company (NEC). This New York City-based theater group, still operating today, sought to support Black actors and playwrights at a time when few theater opportunities were afforded to African Americans. The group’s formation was catalyzed and inspired by the 1959 production of Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun, which gave Black theater people such as Ward, Hooks, and Krone the opportunity to work together.

According to the NEC’s website, one of the group’s first shows was “an evening of black-oriented, satiric one act plays” performed at the St. Mark’s Playhouse at 35 St. Mark’s Place/133 Second Avenue. Through this performance, Ward won an Obie Award for acting and a Drama Desk Award for writing. He was also granted the opportunity to publish a New York Times opinion piece titled “American Theater: For Whites Only?,” which called for the creation of a Black theater company. The article caught the attention of the Ford Foundation, which arranged a grant to support the official formation of the Negro Ensemble Company in 1967. The momentous inception of the NEC was praised by both Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Roy Wilkins, the Executive Director of the NAACP at the time. The NEC continued to make a home at the St. Mark’s Playhouse through at least the early 1970s.

Since 1967, the Negro Ensemble Company has produced over two hundred plays and nurtured the careers of over four thousand individuals. Phylicia Rashad (who played Clair Huxtable on The Cosby Show), Laurence Fishburne and Angela Bassett (who played Ike and Tina Turner in What’s Love Got To Do With It), Richard Roundtree (who played the title character in Shaft), Louis Gossett Jr. (who played Emil Foley in An Officer and a Gentleman), and Sherman Hemsley (who played George Jefferson in All in the Family and The Jeffersons), are among the hundreds of actors whose talents were fostered by the Negro Ensemble Company. The company, now located at 135 West 41st Street, continues to support Black artists and present performances by and about Black people.

This information can also be found in the African American History Tour in our East Village Building Blocks map.

Roberta “Robbie” Kaplan, 37 West 12th Street

Lawyer Roberta “Robbie” Kaplan (b. September 29, 1966), who lived at 37 West 12th Street, is perhaps best known for arguing the 2013 Supreme Court Case United States v. Windsor. This case involved Edith “Edie” S. Windsor (June 20, 1929 — September 12, 2017), whose lifetime partner Thea Clara Spyer (October 8, 1931 — February 5, 2009) passed away in 2009. Because the federal government did not recognize Windsor’s marriage to Spyer, Windsor was required to pay $363,000 in federal estate taxes upon Spyer’s death. Windsor requested a tax refund and was denied due to the Defense of Marriage Act, which prohibited the Federal government from recognizing same-sex marriages.

Nevertheless, Windsor persisted, and with Kaplan pushed the case until it reached the Supreme Court. In a landmark moment, the court cited the Fifth Amendment guarantee that people cannot be “deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law,” and ruled in Windsor’s favor. In states that recognize same-sex marriage, it stated, couples are entitled to the same federal benefits. The decision was a crucial step toward the 2015 decision in the case Obergefell v. Hodges, which decided that same-sex couples had the right to marry anywhere in the country.

As documented on Kaplan’s website, “Professor Laurence Tribe of Harvard Law School has observed that he cannot ‘think of any Supreme Court decision in history that has ever created so rapid and broad a lower-court groundswell in a single direction as Windsor.’” Kaplan has a strong commitment to applying the law to fight for the public interest, and has pursued many other significant civil rights cases. These include a case seeking marriage equality in Mississippi, a case that overturned Mississippi’s gay adoption ban, and a lawsuit filed against the 24 neo-Nazi and white supremacist leaders responsible for organizing the racist attacks in Charlottesville, VA in 2017.

This entry can also be found in the LGBTQ Sites, Transformative Women, and Social Change Champions Tours in our “Greenwich Village Historic District: Then & Now Photos and Tours” map.

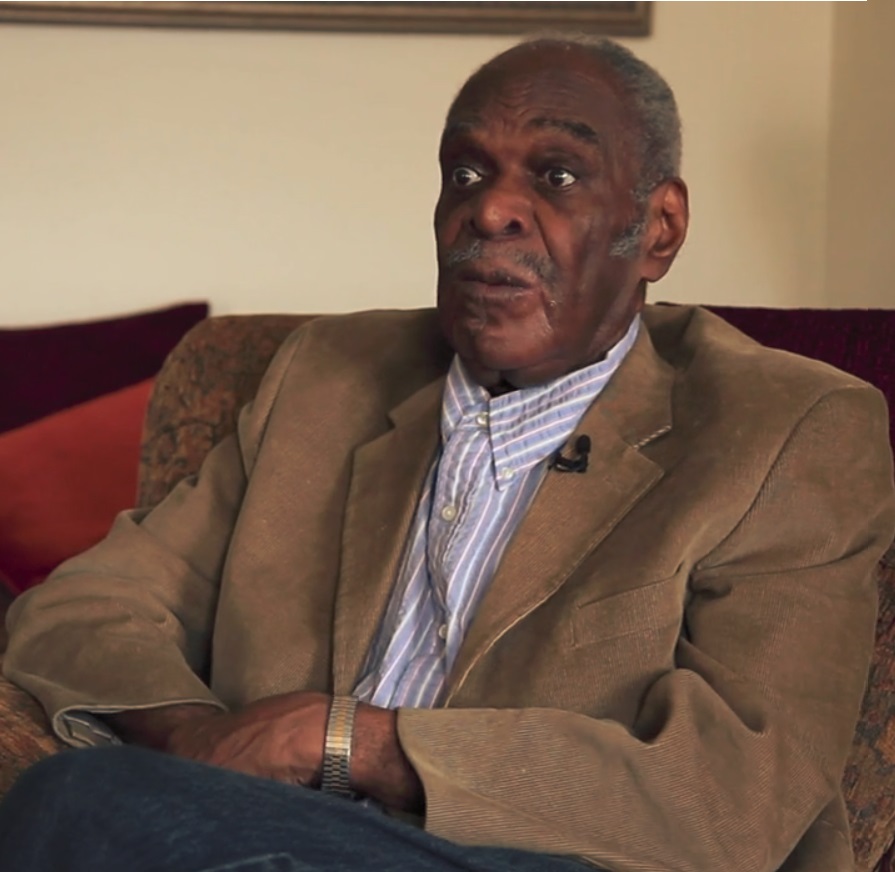

William Kunstler, 13 Gay Street

William Moses Kunstler (July 7, 1919 – September 4, 1995), who owned, lived at, and maintained an office at 13 Gay Street, was an American radical lawyer and civil rights activist best known for his involvement in some of the most high-profile and controversial civil rights and civil liberties cases of the late 20th century. A lifetime New Yorker, he attended DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, Yale University, and Columbia University Law School in 1948. Kunstler practiced family and small business law in the 1950s, and was an associate professor of law at New York Law School (1950–1951) before entering civil rights litigation in the 1960s. Kunstler’s successful defense of the Chicago Seven from 1969–1970 led The New York Times to label him “the country’s most controversial and, perhaps, its best-known lawyer.” He is renowned for defending the Attica Prison rioters, and members of the Catonsville Nine, the Black Panther Party, the Weather Underground Organization, the American Indian Movement, and many other radical figures and civil rights efforts.

In 1961, while working with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), Kunstler defended the activists participating in the Freedom Rides, who challenged segregation on interstate bus travel. At this time, he met Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who commended Kunstler on his work as a civil rights lawyer, and invited Kunstler to speak at the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) annual convention. Dr. King and the SCLC proceeded to refer to Kunstler numerous cases throughout the 1960s. These included defending Fred Shuttlesworth in an appeal that emerged from a 1958 Birmingham bus protest, and representing the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party as it fought to unseat the Mississippi convention delegation. From 1964 to 1972, Kunstler served as the director of the ACLU. Kunstler lived and worked at 13 Gay Street until his death in 1995.

This entry can also be found in the African-American History and Social Change Champions Tours in our “Greenwich Village Historic District: Then & Now Photos and Tours” map.

More Civil Rights and Social Justice Leaders

These three remarkable sites are just a small sampling of the many civil rights and social justice history landmarks in our neighborhoods. In our map, you’ll find well-known landmarks like the Stonewall Inn and Judson Memorial Church, locations key to the founding of the ACLU and the Young Lords, and the places where Lorraine Hansberry wrote and Bella Abzug lived. You’ll also encounter former sites of some of our city’s first African American and abolitionist churches, the building where the NAACP’s iconic “A Man Was Lynched Yesterday” flag flew, the nightclub where Billie Holiday first sang the anti-lynching anthem “Strange Fruit,” the place where birth control began, and the spots key to the abolitionist journeys of both Abraham Lincoln and John Brown: